David Lynch passed away last Thursday at the age of 78. So much has been said and could be said about the man that it is hard to know where to start. We are all grasping at different ends of one giant elephant. For today I’d like to focus on one narrow appendage of his vast legacy.

When I try and do as Lynch did, clear my mind and let an idea come to me, the first image that rises to the surface is a memory from the spring of 2017, standing on the porch of a Chicago apartment taking a break from practicing with a band that would break up only a month or so later when I moved back to New York. The three of us were buzzing with excitement about Twin Peaks: The Return. In between laughing at jokes about coffee and feverish theorizing about where the show was heading, one of my bandmates sighed and said something to the effect of “man, it just feels like he’s getting away with this one for all of us.” What he meant was that by putting Twin Peaks: The Return in front of so many eyeballs David Lynch was scoring a victory for every artist trying to push the boundaries in whatever small way they could. While artists of many different stripes could take part in this vicarious triumph (my bandmate worked in avant garde theater) musicians have an especially valid claim on Lynch being “one of us”. David Lynch was not only a director who was also a musician, he was a musician’s director. In my view no other American director has had a bigger hand in shaping the sound of late 20th century music, and no other director of his stature carved out as much space for the power of musical performance in his films.

Sound writ large is central to Lynch’s work, whether in the form of his personalized sound design or in the scores provided by his late, beloved composer Angelo Badalamenti. But music also lives in his images. When I think of his work across both television and cinema some of the first images to come to mind are musicians and singers on stage. The Radiator Girl in Eraserhead singing “Heaven”. Isabella Rossellini singing Bobby Vinton and Dean Stockwell lip-syncing Roy Orbison in Blue Velvet. Nicolas Cage commandeering a thrash metal band for an Elvis ballad in Wild At Heart. Bill Pullman honking his brains out on the sax in Lost Highway. Rebekah Del Rio’s showstopper at the climax of Mulholland Drive. All of the performances in Twin Peaks, from the roadhouse bands to James’ living room serenade “Just You”. I’m sure there’s an example buried deep in Inland Empire that I’m forgetting. It’s been over a decade since I’ve seen that one and it’s crazy stupid long. If there was a song performed in Elephant Man I was crying too hard to notice it. If anything, Dune’s lack of a musical performance is the surest sign that it isn’t a real part of the Lynch canon.

What drove Lynch to include so many performances in his movies? As with any question about Lynch’s work there is no single satisfactory answer. Readers who can’t accept a deeper meaning to the color of their curtains might declare that Lynch includes so many songs in his movie because he is simply a big fan of music. No one would dispute that Lynch loved music. All of his song selections assemble the portrait of a man with a finely curated record collection. But more than just offering aesthetic pleasure, I think Lynch’s musical numbers serve a dramatic function. Equal parts fabricated illusion and sincere expression, these performances are like Lynch’s movies in miniature. Just as in more conventional movie musicals, these performances are a cathartic rupture in the fabric of the narrative where a character expresses the totality of an emotion without needing to explain themselves. A song needs no decoder ring. The audience either hears it and resonates with the feeling that it offers, or they are left cold. So yes, David Lynch included songs in his movies because he loved music and by loving it understood its full potential.

Music certainly loved David Lynch back. Long before I saw a single episode of Twin Peaks I knew Lynch through a web of allusions, references and open tributes to his universe in my CD collection. “Wrapped In Plastic” by Marilyn Manson. “Black Chamber” by Blind Guardian. “Camilla Rhodes” by Between the Buried and Me. Fantomas’s rendition of the theme from Fire Walk With Me. “Between Two Mysteries” by Mount Eerie. Once I was introduced to the dark side by Blue Velvet I realized that Lynch’s influence extended even further among bands with the modesty to avoid citing him directly. How many indie bands were formed with Julee Cruise at the center of their mood board? How much ominous whooshing has been generated by synthesizers and samplers with hopes of inspiring as much dread as Lost Highway or Inland Empire? Lynch’s influence is so pervasive that writers and editors (myself included!) actively discouraged artists from making the comparison. What is known does not need to be explained.

And with that, I’ll cut this week’s letter short. Anything left to say would be better put by Lynch’s films themselves. I rewatched Mulholland Drive last weekend and I’ll probably watch Lost Highway this weekend. And speaking of Los Angeles…

# # # # # The Promo Zone # # # # #

David Lynch died shortly after being moved from his home in Los Angeles due to the fires that swept through the Altadena area earlier this month. Lynch, a heavy smoker, had been effectively house-ridden by emphysema. If the damage done by these fires felt abstract to you before, here’s a human face. As fires like these become increasingly common in the LA area, it’s crucial that firefighters have the necessary equipment to keep the blaze under control and prevent unnecessary damage. As such, I’m proud to say that People | Places, the record label that Lamniformes calls home at the moment, have put together a 22 track compilation whose proceeds all go to the Los Angeles Fire Department Foundation. Is any of the music featured on this compilation “Lynchian”? The only way to find out is by checking it out below!

I’m still struggling to put all of my feelings about the passing of David Lynch into words. His work meant a lot to me. Luckily I’ve made a few successful efforts in the past to say something about what exactly that meaning is. If you’d like to read more of my writing on David Lynch & music, I’d recommend Drumming Upstream #26 on the subject of “Theme From Fire Walk With Me”

Falling Faster and Faster into "Theme From Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me" by Angelo Badalamenti

Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each of them as I go. Once I’ve learned them all, I will delete my Spotify acco…

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Listening Diary ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Here are five songs that I enjoyed listening to recently! You can find a Spotify playlist with all of this year’s tracks here, updated with a new song every Monday-Friday.

“Etienne” by Ethel Cain (Perverts, 2025)

I wasn’t exaggerating when I said Perverts sounded like an Enemies List release. Tell me this isn’t a Giles Corey deep cut or something off of the first A Silver Mount Zion record. A great fit for the current sub-zero cold snap we’re going through in Chicago.

“Saint” by Björk (Utopia, 2017)

I missed this record when it dropped, but after listening to Björk’s Sonic Symbolism podcast I was inspired to double back and give it a fair shake. This song best matched the vision Björk outlined for the record on the pod, a solarpunk feminist flute paradise alive with bird song.

“Rated X” by Miles Davis (Get Up With It, 1974)

In which Davis invents drum’n’bass 20 years early?? Some absolutely nasty work with the editing on this one, cutting out the burning rhythm section and leaving the organ’s dissonant layers suspended in air before the beat snaps back in. I should have went straight for late period Davis when I was chasing the Francis The Mute high back in 2008, this is exactly what I was looking for.

“rho” by Rei Harakami (Unrest, 1998)

A subtle, percolating electronic dance track that plays some very clever games with a two against three polyrhythm. At any point you can latch on to one rhythm or the other and carry yourself safely to the end of the tune. Because I’m a Playstation baby I hear this kind of production and immediately think about Ape Escape, which reflects well on the taste of Sony executives at the turn of the century.

“Black Apartment” by lkd-sj (World’s End Fruit Basket, 2009)

My apologies for the Spotify link. Japanese music distribution practices are not always cooperative with my newsletter style guide. This track is out of place in more ways than one. It’s hard to tell if ikd-sj were ten years late to the nü-metal party at it’s peak or ten years early to it’s pandemic era second wind. The flirtations with post-rock and shoegaze in the latter half of the record encourage the generous reading of their place in history, but this track is pure 1998. Of course that’s no problem for me. Menacing, slow grooves and a singer who sounds genuinely unwell will get my attention in any year.

\ \ \ \ \ Micro Reviews / / / / /

Here are five micro reviews of albums from my vast Rate Your Music catalog. Long time Lamniformes Instagram followers will recognize these from my stories, however they’ve been re-edited and spruced up with links so that you can actually hear the music instead of just taking my word for it.

Heaven and Hell by Black Sabbath (1980) - Heavy Metal

Sabbath’s first album with Ronnie James Dio, the short king of metal, as their singer. Out with drugged out hippie psychedelia, in with high fantasy and higher notes. That Iommi and co. changed their sound so drastically and still killed it is a testament to their status as all timers. As much as I love the Ozzy stuff, this is my favorite Sabbath album. The title track, “Children of the Sea”, “Die Young” and “Lonely is the World” are all bulletproof. Dio performs every line like its vital to your survival. The man was an absolute ham in the best way. Iommi’s lead playing also really went up a level on this album.

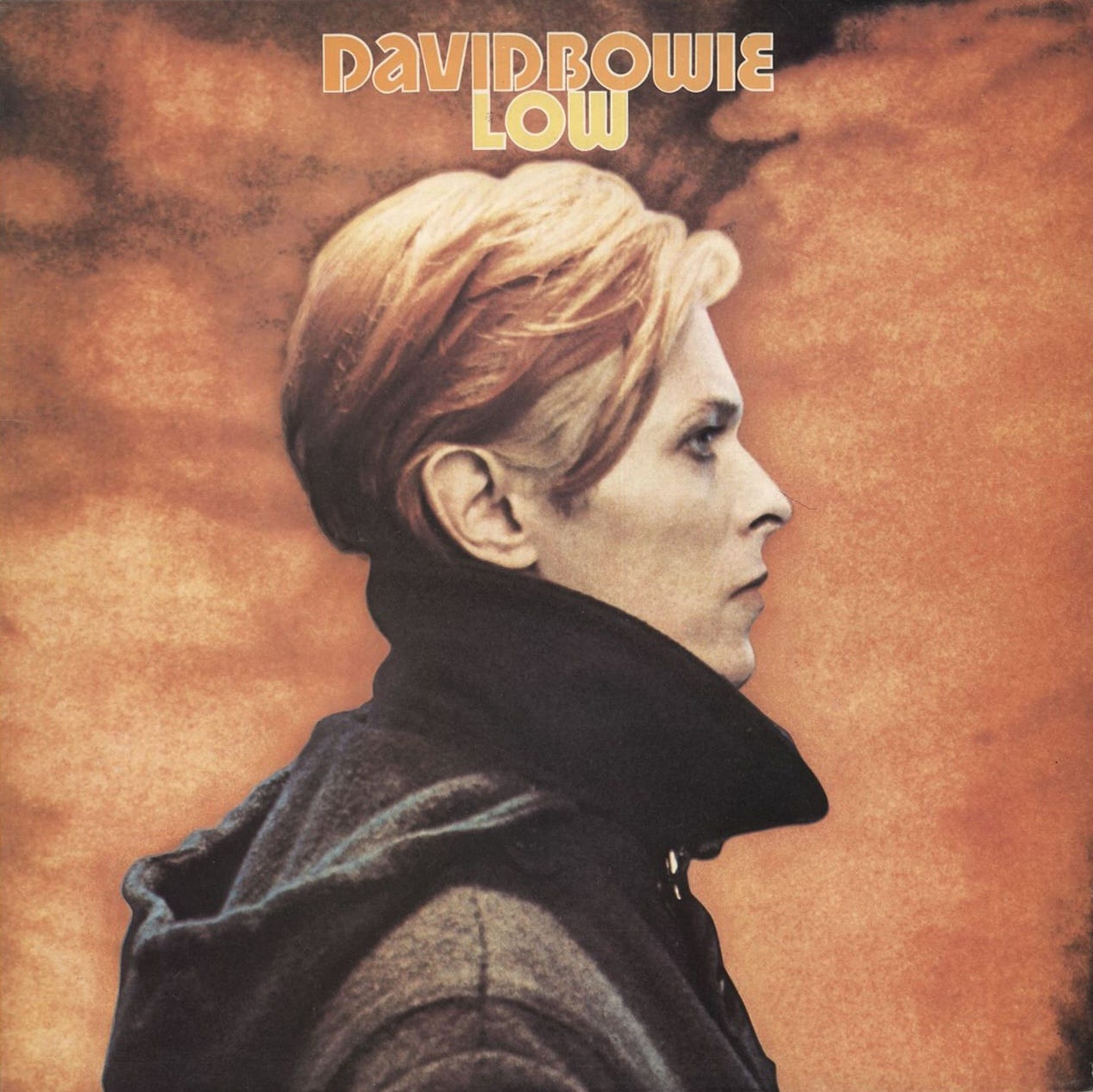

Low by David Bowie (1977) - Art Rock

The first of Bowie’s much ballyhooed Berlin trilogy, in which, with help from Visconti and Eno, he rebuilt himself from the coked-out hell of his Thin White Duke period. What I love most about this album is its split structure: one half damaged art rock, one half mournful ambient. Clearly the work of someone Going Through It, the pop songs feel like an artist learning to speak again while the ambient sections are pure musical expression. I don’t know if this is my favorite version of Bowie, but in many ways it seems like the most human version, in part because it is so awkward and alien.

Symbolic by Death (1995) - Death Metal

I’ve mentioned a few times in these reviews that coming back to Death as an adult I’ve found their songwriting lacking in logic. That’s true of this record too, but it hardly matters. Symbolic is a parade of perfect riffs. Even if the transitions between them don’t always work, the sheer quality outweighs the sloppy construction. Not the super team of past Death albums, but Schuldiner & Hoglan put up Kobe & Shaq numbers on this one. Really can’t say enough about Hoglan’s drumming here, just the perfect balance of power, precision, and creativity. The way he uses cymbals and bell accents to balance out his double kick patterns is a work of art.

Ki by Devin Townsend (2009) - Progressive Rock

One of metal’s most maximalist singer/songwriters get sober, loses the skullet, and turns down the volume. Working with a band of non-metal session musicians, Townsend rebuilds his style from the ground up. Sometimes the old monster bursts through, but most of this album is the sound of a man slowly gaining control of his demons. It’s also gorgeous, just impeccably mixed. I wish more bands would try the weird metal-meets-soft-rock aesthetic Townsend has going on here, but I don’t know if anyone else could actually pull it off.

City by Strapping Young Lad (1997) - Industrial Metal

One the opposite end of the HeavyDevy catalog we have City, a torrential downpour of rage. Back up by Gene Hoglan (continuing the metaphor from the Death review above, this would be Hoglan as Shaq on the Heat) Townsend unleashes non-stop vitriol over cacophonous industrial metal. Even in this relentless onslaught Townsend’s tunefulness still rings true. The guy can’t help but write beautiful harmonies, even over gnarled double bass bullet hell. The first defining work of one of metal’s true geniuses.