Last week in my assessment of Pitchfork’s Best Songs of the 2020s list, I asserted that Chat Pile’s elevation to the level of the previous decade’s darlings Deafheaven signaled that the publication had firmly shifted away from poptimism. I was not happy to reach this conclusion. I had privately made an addition to the Lamniformes Cuneiform Style & Substance Guide to prohibit any lengthy discussion of poptimism. I only made the exception last week because I was bringing poptimism up only to bury it. The subject is not worth discussing except in the past time. I cannot believe that in 2024 I’ve had to scroll past headlines grousing about poptimism’s grim impact on music criticism. The horse is long buried! Stop trying to dig it up!

I am not here to complain about complaining. Another tenet of the Lamniformes Style & Substance Guide, borrowed from Mad Men’s Don Draper: “If you don’t like what is being said, change the conversation”. In that spirit, let’s talk about Progmatism.

I’ll admit it, when I suggested in 2019 that Progmatism should be the prevailing critical mode of the 2020s I was more concerned with the word’s prefix than the suffix. I’ve never hid my love for progressive rock and it’s various offshoots. I believed then, and still do now, that the genre offers a line of escape from the “pop” vs “rock” binary. Pragmatism, the quintessentially American branch of philosophy, was mostly just along for the ride. Well, I’ve listened to a lot more music and read a lot more books since 2019. It turns out that pragmatism has just as much to offer as prog does when it comes to moving on from the poptimism vs rockism debate. Part of the reason it has taken me five years to elaborate on my silly music critic portmanteau is that I always started with the prog part of the argument and found myself in a maze of clarifications. This time I’d like to try the argument from the other end, which I think will save me a lot of leg work once I start bringing up Peter Gabriel, Omar Rodriguez Lopez, and the rest.

I’m roughly half way through Objectivity, Relativism, And Truth by Richard Rorty (1990). One of the central parts of Rorty’s perspective in these essays is that in their search to nail down objective facts about reality both scientistic and religious thinkers inevitably have to rely on metaphysical arguments. To Rorty, the introduction of metaphysical conceptions of “goodness” or “truth” to the conversation only serve as invitations to waste a lot of time. There’s no way, in Rorty’s view, to drill all the way down to an objectivity truth about the world that doesn’t rely on a human understanding of that world. We are incapable of stepping outside of our own perspective and looking at it “clearly”. Instead of bothering with this impossible outsider’s view the pragmatist accepts that their view, values, and understanding of the world are necessarily contingent on the time and space in which they were born. Absent a metaphysical and immutable “true” or “good”, the pragmatist uses whichever understanding of these words are most useful to the conversation at hand. Our understanding of the world has to shift depending on the demands of the particular language game we happen to playing.

Rorty’s argument for this loose, pragmatic approach to reality is a little too rigorous for a philosophical dilettante like me to re-cap accurately. But while reading Objectivity I was struck by the similarity between Rorty’s critiques of scientism & idealism and my issue with rockism & poptimism. To me, despite their apparent differences rockism and poptimism both assess music on the basis of a metaphysical value system. I’ll try to explain.

Rockism, as defined in Kelefa Sanneh’s “The Rap Against Rockism” 20 years ago in the New York Times, is a critical mode that values “real” and “authentic” music over “fake” music. In the rockist view good music is made by “real” musicians, ones that play their own instruments, write their own songs etc, while bad music is made by “fake” musicians, i.e. pop artists, DJs, industry hacks and so on. Rockism swears off selling out or bending to commercial trends. The rockist hero is the underground rock band that succeeds in spite of the prevailing culture (Arcade Fire winning the Best Album Grammy with The Suburbs) or the the legacy act grandfathered into realness by their ability to transcend the fakeness of the moment. Sanneh argued in his original article that this unstated but pervasive critical ideology limited the kinds of artists that could be “real” in a way that reflected racial, sexual, and gender divisions. In short, the rockist thinks that straight white guys with guitars are legit and everyone else is fake.

Poptimists, building off of Sanneh’s observations, attempted to expand the definition of legitimacy into territory that the rockists had forbidden. Rap, disco and its dance music progeny, R&B, and anything else that fell into the nebulous category of pop were in the poptimist’s eyes all just as worthy of critical examination and exaltation as any rock’n’roll band. And when poptimists did focus on rockism’s home turf, they did so with an eye for perspectives usually left out of the conversation, i.e. the perspectives of women and people of color playing rock music. This expansion of the field necessitated a concurrent expansion of the critical body. Only a more diverse range of critics with the appropriate cultural knowledge could make legitimate claims as to which releases deserved praise in this new system. These critics could then argue on behalf of the new poptimist heroes and make a case for their justified inclusion in the canon.

This undeniably had positive results. Forms of music-making that previously fell outside of the traditional rock band set up (sampling, programming, producing writ large etc) are now recognized as legitimate practices in any reasonable conversation about music. Speaking personally, the poptimist era made me a much more open-minded and easy-going listener. However, poptimism never fully escaped the metaphysical ground rules that rockism laid down. On paper poptimists stood in opposition to the values of rockism. In practice however, things didn’t quite go that way. Instead of overthrowing the cult of real music, poptimism merely expanded the category of realness. To argue to a generalized readership why a given record mattered more than another, poptimists positioned the artists as authentically representing a real world community and offering an authentic perspective on real world issues. The bigger the artist’s platform and the more people this authentic perspective reached the better. In other words, good music was that which is most real to the most people. Through this populist/utilitarian lens, realness as the ultimate good was stretched into relevance as the ultimate good. The poptimist hero is therefore the pop star who makes the most of their platform in service of a relevant theme.

What irks the progmatist about both the rockist and the poptimist is that “realness” and “relevance” will always be moving targets. Both exist outside of the music itself and neither can be pinned down to a single definition that it true in all cases. No rockist can prove what the most “real” music is without relying on their individual perspective. The poptimist attempts to avoid this problem by pointing to industry approved metrics like ticket sales, streaming counts, and social media followers. While these metrics are standardized and measurable in a way that rockist values are not, the poptimist can’t connect them cleanly to any statements about musical quality. If musical quality is truly a numbers game then of what use is the critic? But if musical quality can’t be tied solely to statistics, what’s the use of referencing them at all? To quote Immortal Technique: “If you go platinum it’s got nothing to do with luck/it just means a million people are stupid as fuck”.

The progmatist when faced with these supposedly objective measurements of quality responds by asking “who cares?”. Who cares if the music is “fake” or made by posers? Who cares if the music is unpopular or irrelevant? All that matters is whether the artist is sick with it and doing dope shit. What “being sick with it” looks like and what “dope shit” sounds like changes depending on the art and artist in question. Without the lingering question of realness or relevance holding them back, the progmatist uses whichever rubric leads to the most productive and interesting analysis of the music. Those rubrics will inevitably be contingent, but what’s the problem with that? With the state of the music criticism game as hobbled as it is, we should all feel free to be as idiosyncratic as we want. And few genres encourage idiosyncrasy as loudly as prog. But this email has gotten long enough, so I’ll save the prefix portion of my argument for next week. Thanks for reading and see you then!

# # # # # The Self Promo Zone # # # # #

Life in Chicago has been pretty good so far! After living in NYC for seven years I can’t tell you how good it feels to chill out in a backyard with a dog. You ever just sit in the sun and not think at all for stretches for 10 seconds at a time? I haven’t just been hanging in the yard, as much as I’d like to. I have also been applying for jobs as I am currently unemployed after the move. Until I land a job (some exciting leads!) this blog and my back catalog are the most reliable sources of income that I have. If you would like to help me buy groceries (we eat so many bananas) consider buying an album from the Lamniformes Bandcamp. Personally, I’d recommend The Lonely Atom. You can also nab a nifty Lamniformes t-shirt, great for the gym, the rock gig, or bed!

Another way you can help with groceries (we also eat a lot of peanut butter) is by becoming a paid subscriber! For the price of one coffee a month, you get early and behind the scenes access to all Lamniformes music, as well as an assortment of other bonuses! Exclusive playlists! Reflections on gigs long past! Maybe other stuff? I just planned a fun series of retrospective content for the end of the year, looking back on my selections of the best songs of the year from the 2010s. If that interests you, consider subscribing below!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Listening Diary ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Here are five songs that I enjoyed listening to recently! You can find a Spotify playlist with all of this year’s tracks here, updated with a new song every Monday-Friday.

“Bounty Hunter” by Undeath (More Insane, 2024)

Hardcore’s scientists have discovered a way to make Cannibal Corpse songs even stupider.

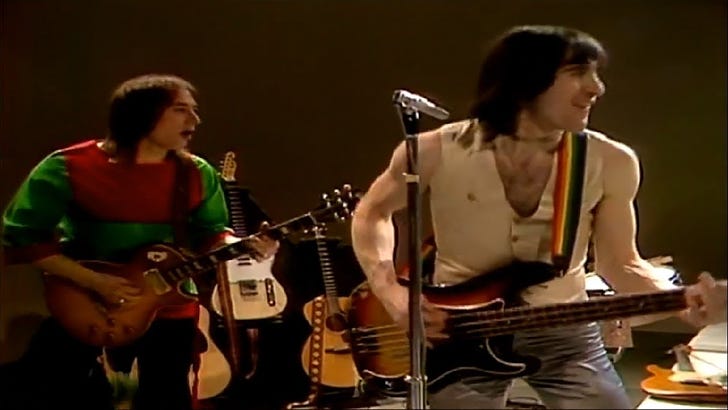

“I Lost My Head” by Gentle Giant (In’terview, 1976)

This video comes courtesy of Alex Van Dorp (Altamira Records). I should devote some time to the Gentle Giant discography. I’d always wrote them off as light weight compared to the big boys of the British scene, but this song suggests that evaluation could stand for an update. Shouts out to the drummer wearing a full Oakland A’s uniform. The prog jock is an under-discussed archetype.

“Ikikäärme” by Oranssi Pazuzu (Muuntautuja, 2024)

This album is as big of a leap for Oranssi Pazuzu as Exhaust was for Pyrrhon. I’ve always looked forward to new records from this reliably surprising Finnish group, but my expectations were far too low for what they delivered this time around. It used to be pretty easy to pitch Oranssi Pazuzu as part black metal part psych rock, but by now they’ve so successfully weaved the two together that their sound can’t be disentangled into its composite parts. If you want to up the ante on your Halloween playlist this year, give this beast of a track a try.

“Disasters” by Touché Amoré (Spiral in a Straight Line, 2024)

An early standout from the new Touché Amoré record. Without busting out the metronome I’d guess its the fastest of the bunch too. This one had me with that little drop out at the start of the second verse. I love the way the chord progression in the chorus is constantly descending, really captures the sense of things falling apart. Combined with the relentless drums we get both sides of “gradually, then all at once”.

“The New World” by Chat Pile (Cool World, 2024)

I love when albums have “almost-but-not-quite” title tracks. It suggests that you have to dig just a little deeper to reconcile the theme of this particular song to the overall thesis of the record. The dots aren’t that hard to connect here, the new world that Chat Pile sing about clearly isn’t a “cool” one, but what plays as a joke on the album level feels more straight-forwardly serious in the song itself. You can tell they wrote this after putting a lot more road experience under their belt. These songs all have big juicy payoffs, the kind you’d write after seeing how & when people go nuts to your stuff IRL. Also, thank you for turning the drums up this time.

\ \ \ \ \ Micro Reviews / / / / /

Here are five micro reviews from my high school and college collection of burnt CDs. Long time Lamniformes Instagram followers will recognize these from my stories back in 2021, however they’ve been re-edited and spruced up with links so that you can actually hear the music instead of just taking my word for it.

Diary of a Madman by Ozzy Osbourne (1981) - Heavy Metal

I have never been interested in Ozzy’s solo stuff post-Black Sabbath (this statement is brought to you by Dio gang). I always assumed that left to his own devices Ozzy was too goofy and radio friendly. I don’t know if I ever listened to this burnt CD all the way through before but it’s pretty cool! Randy Rhodes is the real star, unsurprisingly. The title track is a legit great metal tune with lots of wild twists and turns. Probably not going to revisit the whole thing often, but that title track is a keeper for sure.

1984 by Van Halen (1984) - Hard Rock

Apologies to whoever burned this CD for me: I never listened to it. Van Halen have been one of my rock history blind spots for a long time. I knew “Jump” and “Hot for Teacher” and that’s it. Glad to rectify this today. First off, Alex Van Halen is NASTY on drums. Incredible pocket. The guitar work is obviously great as well. This is fun, definitely the right kind of silly rock’n’roll. Side B is better than Side A. I guess I should catch up on the rest of their good stuff now, huh?

Carriers of Dust by Mirrorthrone (2006) - Black Metal

I can’t remember how I stumbled across this one-man metal project from Switzerland, but stumbling across his Myspace page in 2006 awakened an urge to Influence in my teenage soul. After one listen I was compelled to tell every metalhead I knew about this album. I wanted to be responsible for the virality of the next trendy metal band. Though I’m a little embarrassed about that now, this album was, and still is, an overlooked gem in the symphonic metal scene. Straight up final boss fight music. Songs to laugh manically to. The soundtrack to revealing that this isn’t your final form. Total overkill in the best way, made all the more sinister by the fact that the guy is growling in French. A bit long winded, but come on, that’s the point. If you’re into symphonic black metal you have to check this out.

Waves of Visual Decay by Communic (2006) - Progressive Metal

Remember a while back how I said there were no other bands in the 00s that sounded like Nevermore? When I said that I had forgotten about these guys. The vocal similarity is uncanny. Communic take a much longer-winded approach to songwriting, however. Album starts strong but quickly gets boring. Communic run the Dream Theater additive measure trick into the ground. All the songs are super long for no reason and there are hardly any dynamic shifts. No wonder they’d slipped my mind. Skip.

Cult Classic by Scarlet (2006) - Metalcore

00s math core band from Virginia that never quite broke through to Norma Jean/Dillinger/Everytime I Die levels of popularity. They leaned heavily into a Marilyn Manson-ish industrial aesthetic, which made them unique in the scene at the time but also probably turned a lot of people off from them. I bet that combo of mathcore and mallgoth would have made them pretty popular if they had come out a decade later. This is pretty cool, definitely at its best when it brings in the creepy Deftones-style clean vocals (wow, maybe this band would be even more popular if they’d hit the scene TWO decades later). The lyrics are all “drugs, guns, and sex” in an edgy trenchcoat teen kind of way. Good for what it is.