Welcome to the first entry in my new series Drumming Upstream, in which I learn how to play every song I’ve “liked” on Spotify on drums and write about it.

Side A

“Bobby Jean”

By Bruce Springsteen

Born In The U.S.A.

Released on June 4th, 1984

Liked on June 14th, 2014

Born In the U.S.A. is a popular album. Over 30 million copies sold to date. It is an album that was popular long before Spotify existed. It features Bruce Springsteen’s highest charting single (“Dancing in the Dark,” which reached #2 on the Billboard charts). The title track has been used as a political football, one that conservatives attempt to carry by its chorus into the end zone of patriotism and that the American Left, broadly defined, have consistently reclaimed by pointing to its verses, since before I was born. Born In the U.S.A. is the kind of popular that makes it very difficult to avoid. It is the kind of popular that gets played in the waiting rooms of a doctor’s office.

This is where I first heard “Born In The U.S.A.” in 2007, in the waiting room at a podiatrist’s office while my socks filled with pus. The toenails in both of my big toes were ingrown, and had been in such a state for at least a month by the time I was in that waiting room. I had, despite being in near constant pain when on my feet, not told anyone about this condition until my parents noticed me wincing around the house. I guess I thought it would just blow over and my feet would eventually go back to normal. Later that night I was told, after the doctor had cut out the offending bone tissue, that if I had not said something in time there’s a good chance that I would have lost the whole toe on both feet. So there I was, teeth gritted and feet nearly-rotting, when over the radio I heard a man bellowing his lungs out about his country of birth over a snare drum that sounded like Mike Tyson punching the side of a pick-up truck. “Man,” I thought to myself about the music and just about everything else in my life, “this sucks.”

Seven years later, toes intact, I overcame this bad first impression and listened to Born In The U.S.A. in full. Springsteen had by that time slide across the generation gap and transformed from “music my dad likes” to “music my friends like”. Indie rock bands like Arcade Fire and Titus Andronicus had sold me on Springsteen as an influence on music that I enjoyed1 (you’ll hear a lot more about what I think of at least one of those bands in this series soon enough) and while in college a number of my musician friends drew from the same well. By senior year I felt myself defensively flinch when a teacher of mine let out a derisive sigh after playing “Born In The U.S.A.” the song to demonstrate a feature of its production. I believe he was asking us to pay attention to the heavyweight-sized humanhicular autoslaughting punch of the snare drum. “Hey man,” I thought to myself “that’s The Boss you’re sighing about”.

To be fair to that teacher, Born In The U.S.A. is not my favorite Bruce Springsteen album in large part because of its glossy 1980s pop sheen. I enjoy the big singles from the record, where the shining metallic tone makes the most sense with the songwriting. But a lot of the deeper cuts feel constricted. They sound like they were written and performed with the sweat and friction of a live performance in mind but dressed up in clothes with a higher retail value than the working stiffs that Springsteen’s music is meant to approximate could realistically afford. Most of the songs don’t wear it well.

The exception is “Bobby Jean.” It’s the eighth track on the record, or the second on the album’s B side on the vinyl version. After Springsteen grunts out the tempo the song rides a single insistent piano, bass, and drum groove from start the finish. We’ll get into why I like this groove so much on Side B, but it probably wasn’t what made me hit the green heart next to the song on Spotify. If I had to guess, it was the song’s lyrics that earned it the honor of being the first song on my "Liked” list. In “Bobby Jean” Springsteen, or his fictional equivalent, sings goodbye to a lover or a friend just out of his reach. He goes to their house but they’re already gone. He reminisces about how long he’s known this person, how they shared a love for the same music and faced the same hardships over the years. In the final verse, “Bobby Jean” knocks on the fourth wall:

“Well maybe you'll be out there on that road somewhere / In some bus or train traveling along / In some motel room there'll be a radio playing / And you'll hear me sing this song”

This kind of self-referentiality is hardly unique in popular music (“bet you think this song is about you”, etc) but it carries extra weight here. “Bobby Jean” is a song about indirect communication and being just slightly too late to say how you really feel. This is about as perfect a theme for a piece of recorded music as you could drum up. All recorded music is a lopsided communication, the performer never knowing how or when or who will hear what they’re singing. The audience can only experience the recording as a message from a past, one too distant to respond to. The song is a message in a bottle, lost on a sea of noise.

Around the time that I Liked the song on Spotify I had a conversation with a friend of mine about Born In The U.S.A.. When I mentioned that “Bobby Jean” was my favorite song after a first listen he lit up and told me about the accepted belief among fans that the song is about E Street Band guitarist Stevie Van Zandt, who left the band during the Born In The U.S.A. cycle. That read made sense to me. Some may point to the line “I miss you baby” as proof that the song must be about a former lover, but be honest with yourself, it’d be more surprising if Bruce Springsteen didn’t refer to his close male friends as “baby.” And for what it’s worth, I’ve always thought that the song’s focus on an inability to communicate how you feel until its too late is more potent when describing the unspoken love between two tough guys. In so many of my male friendships I recognize this same hesitancy to say what we really feel, as if acknowledging the contents of our hearts would some how make those contents dissipate into the air. It’s only at the last minute that I realize that if I don’t say it now I never will. The trouble is I never know when that last minute is approaching or if it’s already in the rearview.2

Time passed. The friend who told me this trivia hit a rough patch. For reasons that I won’t get into here, a lot of our mutual friends ended up distancing themselves from him. I stuck around. Not out of some kind of moral obligation, I’m no saint, but because saying what needed to be said was too painful for me to muster. I guess I hoped that it would all blow over and everything would return to normal. Things did get better, but if there’s such a thing as normal it isn’t anything we could ever return to. Still, any time I listen to “Bobby Jean” I catch myself thinking about those years and whether there was something I could have done or said that would have helped. I suppose I’ll never know. So if you’re out there on the road somewhere, I know that I can’t change what happened, but I’m thinking of you just the same. I miss you, baby.

Side B

“Bobby Jean”

Performed by Max Weinberg

133 BPM3

I love the drums on “Bobby Jean.” If I had Liked another song on Spotify first I don’t know if I would have been as enthusiastic to get the ball rolling on Drumming Upstream. Max Weinberg’s performance is simple, effective, and helps demonstrate one of Bruce Springsteen’s signature musical habits, something I call “Declarative Forward Momentum.” Let’s dive in.

After Springsteen counts off, Weinberg sticks to one groove for the whole song. Snare on 2 and 4. Kick on 1 and 3, as well as the eighth notes just before 1 and 3. The hi-hats chug along on eighth notes. Weinberg never moves that eighth note pulse to another cymbal, sticking on the hats for the whole song. The only breaks from this pattern are Weinberg’s fills, which he throws in with increasing frequency as the song reaches its end. All of the fills, with one climactic exception, are single stroke eighth notes and sixteenth notes that never involve his feet. In other words, this is the perfect song to teach someone who is beginning to learn rock drumming. It requires all of the basic skills that you need to play rock music and it teaches by example a lot of good habits you need to play rock music well. Part of the reason that Springsteen’s lyrics hooked me is that it’s very easy to hear them. Weinberg’s fills never cut over the vocal line. The majority of his fills are during instrumental sections of the song, and if he does fill when Springsteen is singing he only darts in at the end of his phrases.

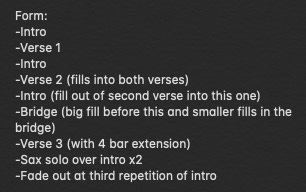

To be clear, I’m not saying that a beginner could have recorded this take. Weinberg is rock solid, has great kit balance, and plays his fills with professional confidence. His time isn’t metronome perfect, the song is mostly in the 133 figure I gave above, but it slows down and speeds up briefly and subtly throughout the song. Turns out that despite the album’s high fidelity pop production Born In The U.S.A. was not recorded to a click. I wouldn’t have guessed until I took the time to count along with the song on the Tempo App. While we’re on the subject, I should probably discuss my process a bit. I had already figured out the groove by ear, so I didn’t need to transcribe it. Instead, I began by making a quick chart for the song’s form:

Then, I counted out the tempo on Tempo, set a metronome to the approximate BPM, and played the groove solo to the click. Once I felt comfortable with the tempo and that I was playing the part with the appropriate feel and dynamics, I played along with the recording a number of times, making note of fills that I missed or moments where I’d slip off of Weinberg’s playing. With these trouble spots identified, I busted out pen and paper and transcribed three specific fills that either I hadn’t figured out by ear or that were leading into parts of the song where my tempo didn’t match Weinberg’s. I practiced those fills, played along with the song a handful more times and then recorded and filmed four takes. The video you see below is Take #2.

If this were a recording session, I would probably punch in a better version of one fill in this take but otherwise I’m happy with this performance. It’s a lot of fun to smack the heck out of my snare and all unleashing those big fills under Clarence Clemons’ saxophone solo is the perfect payoff after the wistful end of the third verse.

But let’s get back to that needlessly wordy piece of jargon I threw at you in the first paragraph of Side B: Declarative Forward Momentum. What I’m trying to describe here is the effect that Weinberg’s playing, in conjunction with the harmonic rhythm of the song, has on “Bobby Jean” and the audience. The bass guitar and piano, played by Gary Tallent and Roy Bittan respectively, are glued to the same “and 1… and 3” pattern that Weinberg’s playing on the kick drum. The chords that Tallent and Bittan are playing also change along with this pattern on the "ands” so that they change just ahead of the start of each measure and then pound the chord twice in a row. This rhythm shows up all over Springsteen’s music, think the “NO I’M! A MAN!” chorus of “The Promised Land,” and it’s one of the go-to tricks that other bands use to make their songs sound like Springsteen, for example Arcade Fire’s “Intervention”4. The rhythm evokes forward momentum because of the way that the harmony pushes ahead of the barline. The declarative part comes from how thuddingly obvious each chord change is, almost like the second hit is an exclamation point to the first. I’m not a driver, but this groove feels like what I imagine cruising on the highway feels like from behind the wheel. Once you get it up and running you barely need to check in on it. It’ll carry you wherever you’re looking to go, one measure at a time.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

Since “Bobby Jean” is the first entry in Drumming Upstream it will stand alone at the top of the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard:

“Bobby Jean” by Bruce Springsteen

For those that want to listen along with this project, you can hear the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard in this playlist

Putting this first entry together was a lot more work than I expected, so I’m not sure if I’ll be able to get to the second entry ready for next week’s newsletter, but it will feature a song that hardly resembles “Bobby Jean” at all. In fact, it doesn’t even have “real” drums on it! See you when I see you. Good luck, goodbye.

I had another possible entry point around the same time in Light This City’s melodeath version of “Born To Run.” However that doesn’t fit into the category of music that I enjoy. No knock on the band, they’ll also show up in this series, but the cover doesn’t work.

When I was working on the outline for this entry Montana Levy, the biggest Bruce Springsteen fan I knew, was still alive. I’ve already written about how much I wish I had said to her if I had known that we had such little time left. I won’t go over it again here, but her death will hang over this song and every other Springsteen song in this series.

That’s “beats per minute,” the standard measurement system for tempo.

Arcade Fire will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream.