Welcome back to Drumming Upstream! I am learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each of them as I go. Once I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 457 songs left to go!1

This week I learned “Black Man”, a deep cut from Stevie Wonder’s legendary ‘Songs in the Key of Life’ record.

Side A

“Black Man”

By Stevie Wonder

Songs in the Key of Life

Released on September 28th, 1976

Liked on May 1st, 2015

There is a line between timeless and of-its-time, and that line is harder to find than you’d think. Stevie Wonder stands so confidently across that divide that he complicates the very idea of the line. Stevie Wonder is timeless, self-evidently, because his music has remained popular with just about everyone for decades after its creation. And Stevie Wonder is of-his-time, because in order to understand why his music is significant, and why it sounds the way it does at all, you must know when and where it comes from.

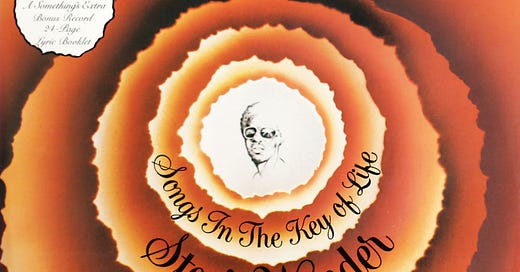

Writing about Stevie Wonder is mighty intimidating. To consider him deeply feels like considering the very concept of the American popular musician. The man checks almost every box. Child prodigy. Crowd-pleasing singer of written-by-committee pop songs. Ludicrously talented multi-instrumentalist. Writer of genre-exploding pop songs. Socially conscious Real Artist. Adult contemporary icon. Revered legend. His music is upbeat and positive without being frivolous, ambitious and high-minded without being dour or humorless, made with cutting edge technology without losing tradition, unapologetically Black but aiming to please and include everyone, sexual but family-friendly, bottomlessly complex and casually palatable, altogether, all at once. No artist so monumental could ever be boiled down to a single song. However, for our purposes we could do worse than “Black Man”, the last song on the third side of 1976’s Songs in the Key of Life, Wonder’s 18th studio album, and a double at that.

Songs in the Key of Life is the poptimist holy grail. It sits, glittering and enormous, at the seat of honor in Stevie Wonder’s discography as the culmination of his most celebrated period. After spending the 1960s pumping out albums of covers and working as part of the Motown songwriting team, Wonder took complete control over his career in the 70s. In that decade he released a string of six increasingly ambitious albums, self-recording many of the instruments (including the best new synthesizers on the market) and expanding his lyrical focus to include weightier topics like race, class, and religion. Incredibly, his music only got more popular during this maturation period. Unlike say, Scott Walker, who abandoned fame and fortune to realize his wild artistic aims, Wonder negotiated a seven year, $13 million contract with Motown in 1975 ahead of Songs’s release. In 2022, that’d come out to $68 million2. With that much cake, deliberating over having and eating isn’t on the menu anymore.

Wonder’s career somehow got even more successful after Songs in the Key of Life. By the time I was old enough to interface with his music he’d transcended into an institutional fact of life. There he was on Sesame Street, or in the background of a rap video, at an award show, or endlessly in my music school coursework. I had one teacher that used “Overjoyed” as an example of at least three different harmonic concepts in at least three different classes, to say nothing of the amount of times that I had to play “Superstition” in ensembles. Wonder’s ubiquity, particular during my academic years, made it hard for me to hear his music on its own terms. The whole scene just felt old-fashioned and safe, not qualities that a young 20-something in all black typically goes for. My breakthrough came when it was imperative that I ignore that something was seriously wrong in my life. On a particularly beautiful spring day this desire for distraction inspired me to play the most positive music I could think of. I settled on Songs in the Key Life. I listened to the first side while picking up breakfast in Lakeview in Chicago. By the time I came home I put the rest of the album on in the house and smiled with lip-cracking intensity at my girlfriend to say “isn’t this all just great?!?”. She didn’t agree, but the record stuck with me. When I got to Side C I was so punch-drunk from the record’s relentless pace of great tunes that I slapped a Like on “Black Man” like I was saying uncle. Stevie Wonder won. I was converted, even if my relationship was doomed.

“Black Man” is one of two songs on Songs written in collaboration with Gary Byrd, a radio DJ from New York City. As suggested by the big L word in album’s title, Wonder’s lyrics tackle life from beginning to end, describing his journey from childhood to fatherhood and much in between. Byrd’s contributions serve as the stand-in for Wonder’s political life. Throughout his classic 70s period, Wonder’s abilities as an arranger grew in tandem with his political consciousness. That simultaneous growth bore the fruit of hit songs with lyrics that clashed meaningfully against their accessible accommodations. Genuine frustration with Richard Nixon transmuted into a dance tune, the plight of the homeless rendered in a miniature Soul-Opera, that kind of thing. Wonder’s political lyrics during this period were charged more by empathy than rigor. Don’t throw on “Living For The City” and expect Adorno, is all I’m saying. Byrd was presumably brought in to provide specifics where Wonder usually settled for generalities. His two contributions immediately stick out, not just from the rest of Songs in the Key of Life, but from the previous socially-minded Wonder tunes. The first, “Village Ghetto Land”, is as bitterly ironic as Wonder’s music ever got, setting lyrics about urban decay and desperate poverty against a sickeningly ornate orchestra of synthesized strings. The song ends by demanding more from its audience than just gratitude or positive thinking, the question of “would you be happy” under such circumstances lingering even as the album charges forward into the jazz fusion instrumental “Contusion”.

Byrd’s second contribution is just as demanding of the audience but aims to uplift rather than accuse. Inspired by the United States Bicentennial that summer, Byrd and Wonder argue that celebrating American history is only possible by acknowledging the contributions of all Americans. “Black Man” is an ode to multiplicity and the universality of the American Dream, concluding at the end of each chorus that “this world is made for all men”. Keeping in mind the song’s origins at this exact moment in history, 1976 in the United States, is crucial to understanding why “Black Man” would have sounded pretty radical at the time of its release. Because uh, it sure doesn’t sound that way in 2023.

To the progressive-leaning listener in 2023, “Black Man” might seem both paltry in its political aims and woefully dated in its choice of words. Each verse follows the format of listing an achievement and then attributing it to a “[blank] man”, filled in with the skin color of the achiever. This brings Wonder dangerously close to using a slur that even the NFL steers clear of these days when singing about Native Americans. There’s also the question of which achievements Wonder & Byrd highlight in “Black Man”. Is Christopher Columbus’s expedition to the Caribbean really something that we should celebrate? Are Bruce Lee and exploited railroad workers really the best we can do in giving Asian Americans their due credit? To be fair, Byrd and Wonder include a wider range of inarguably accomplished individuals in the song’s closing call-and-response, including doctors and educators that have contributed more than just some cool martial arts movies. But even this extended back and forth doesn’t hit the same in the present day. Why are the teachers barking like drill sergeants? Is this what Republicans think “critical race theory” means?

The past is an easy target for jokes like these, but criticizing Wonder and Byrd for the way that the culture has changed in their wake feels cheap. Better to look beyond the questionable surface level decisions and instead look at the underlying intention. Focus on the doughnut not the hole. “Black Man” is socially progressive, but it is not revolutionary. Its criticism of the status quo only comes by implication. Instead it responds to the patriotism of the bicentennial moment with “yes, and…”. This optimism for the American project and sincere, maybe even naive, celebration of American history is what really makes “Black Man” seem old fashioned in our post-Rage Against the Machine context. And while I’d probably take that improvisatory yes-anding into more radical territory than a guy who just collected the equivalent of $68 mil would appreciate, I can’t help but sympathize with what Wonder and Byrd tried to do here. A musician at the peak of their creative powers and near the peak of their popularity spending eight minutes to argue for the dignity of all Americans, specifically the one’s typically denied this dignity, is worth applauding even if it is clumsily executed.

Plus, it, uh, sounds fucking incredible.

Side B

“Black Man”

Performed by Stevie Wonder

109-110 Bpm

I suspect at least a few readers unfamiliar with Stevie Wonder may have raised their eyebrows at the header for this section. Though far more well known for his work at the keyboard or, if you’re a Drake fan, for his harmonica solos, Stevie Wonder is a hell of a drummer. In fact, Wonder played drums on nearly every song on Songs in the Key of Life, including “Black Man”. Other, more obsessive readers might have also raised their eyebrows at how long this song sat on my Liked list before making it into Drumming Upstream. These two eyebrow-raising pieces of information are related. “Black Man” took a long time to learn because Stevie Wonder is really, really good at drums.

The first hurdle I had to clear was figuring out what Wonder was playing. “Black Man” is a dense song in addition to being a long one. Wonder’s drumming hides behind a web of clavichords, Fender Rhodes, bass lines, horns, and percussive noise generated by Wonder’s synthesizer experiments. As well mixed as Songs is, this thick arrangement makes it hard to hear where drums begin and everything else ends. Frustrating for the student drummer, to be sure, but a listener’s delight. The whole song ripples with waves of sound. Wonder stuffed so much polyphony into “Black Man” that it practically collapses back into monophony. Does the song need this much stuff in it? Sure! If you’re going to write a song about including everyone, you might as well make it sound like everyone is playing on it (even if you just did most of it yourself). Moreover, “Black Man”’s maximalism fits right in with the rest of Songs. Just as the album overflows with songs, each song overflows with itself.

In order to better make out what Wonder played on “Black Man” I checked two supplemental sources. First, I watched videos from Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life tour from 2014. Live, Wonder sticks to his keyboard station, leaving the sticks to Stanely Randolph. Randolph is a serious player in his own right, the kind of guy that gets called for major pop star gigs on short notice. He’s also a YouTuber with plenty of great drum cam footage in his library, including two different performances of “Black Man”. Eureka! Just to be safe, I also tracked down the Classic Albums episode on Songs in the Key of Life, in case there was any behind-the-scenes looks at “Black Man”’s original recording. Once again I struck gold. 57 minutes into the documentary, Wonder and his engineers3 go through the song’s layers one-by-one, including a few clips of isolated drums. I couldn't have asked for a clearer demonstration.

There was only one problem: Wonder's original part and Randolph's live versions aren't the same. The two versions share some similarities. Both are your standard snare-on-two-and-four backbeat, spiced up with tom accents that rotate on a two measure cycle. Randolph and Wonder don’t place their toms in the same spots in that pattern though. Wonder’s tom accents reliably fall on the 16th notes just before beats 3 and 4. Randolph’s first tom accent fits that pattern, but then he skips the hit before beat 4 and instead includes a completely different pair of accents in the second measure. What gives? My guess is that Randolph changed the part for ergonomic reasons. With a standard drum kit, using your left hand to play consecutive 16th notes on a floor tom and a snare requires an awkward pull on your shoulder at high speeds in tandem with quick twitch movements in your fingers and/or wrists. Ouch. Can’t blame the guy for going with something a little easier to play for ten minutes straight.

Without footage of Wonder recording the original take, I can’t say for sure how Wonder managed to record the part without tearing a rotator cuff, but I had a hunch. Instead of playing the snare on beat four with my left hand, I tried bringing my right hand over from the hi-hat to the snare while pulling my left back to starting position at a more comfortable pace. This might all read as nonsense if you aren’t a drummer, but this is a deeply unconventional way to stick a drum beat. The move risks all sorts of traffic jams between your two hands. Encouraged by Wonder joking about smacking the sides of drums and microphones by accident on the final take for “Black Man”, I stuck with it. Eventually this strange move started to feel totally natural.

With the song’s core groove under my hands most of my work was complete. “Black Man” rides that groove from start to finish with no substantial changes. However the part is far from static. Wonder throws in all sorts of quick fills and unique accents throughout the song. Each verse has its laundry list of details: extra splashes on open hi-hats, rolls on the toms, crashes where you don’t expect them, etc. I picked out some of the most ear-catching deviations, like the string of syncopated accents at the end of the bridge or the massive triplet fill around the kit at the end of the third chorus, and learned them as closely as I could.

I could have kept getting more granular, but… I don’t know. Something about recreating Wonder’s drum part exactly 100% right felt like an imposition of order on a part that was loose and jammy in its origins. Besides, Randolph’s version proved that Wonder was open to alternatives. I decided that the spiritually correct way to approach the song was to have fun and play my own fills. Huge load off, let me tell you. Knowing that I wouldn’t have to restart the whole take if I played four snare hits instead of two for a given fill freed up a bunch of mental CPU that I could devote to playing well rather than playing “right”. There’s one fill in my final take that I’d do over if I could, but given how this performance ended I couldn’t bear to post any alternate take. You’ll see what I mean when you watch the video below.

The tom part I settled on is a bit busier than either Randolph or Wonder’s version, but I loved the way it felt in my hands and it locks in with the bass part in a cool way, so I stand by the extra notes. The big triplet fill took a long time to get right. I knew that Wonder was a good drummer before learning this song, but I had no idea he fired off fills this fast. If you listen carefully you’ll hear me shout “woo!” after I land the fill, and then temper myself with “don’t get cocky, kid”. I’m not usually a Star Wars quoting individual, but it felt appropriate for the song’s late 70s vibe. Speaking of appropriate, I wore my “Medicare For All” shirt. This world is made for all men, yes, and they all deserve healthcare.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

I’ve long thought of “Black Man”’s placement on my Liked list as a stand-in for Songs in the Key of Life as a whole. When I first Liked it, I didn’t know that even better songs further down the track list would soon eclipse it (“Another Star”, holy shit), and I hadn’t spent enough time with the record to appreciate how good the singles ahead of it truly are. I cycled through periods where I was completely sick of “Black Man”, mostly because of the long call-and-response with kids segment at the end of the song. The groove remained undeniable, but those eight minutes gave me a lot of time to nitpick lyrical/political (polyrical?) issues out of the otherwise immaculate wall of sound. Learning the song has forced me to make peace with Wonder’s centrist platitudes and better appreciate his broader aims as an artist. It also forced me to reckon with how good a drummer he is. I can’t walk away without being impressed, I’m just less impressed by “Black Man” specifically than I am with Wonder and Songs as a whole. For now, the song will rest at number 16 on the Leaderboard, above Tim Hecker’s “Virginal II” and below Scott Walker’s “Bolivia ‘95”.

“Black Man” by Stevie Wonder

The next entry of Drumming Upstream is an inverse of this one. Instead of learning a song I’m lukewarm on from a record I love, I learned a song I like from a record that I otherwise don’t. We’ll get into it next week. Hope you have a pleasant time until then.

Over my break I discovered that I had Liked a song twice, so I removed one of the duplicates. Three cheers for a slightly reduced work load.

Basketball fans will note that this is what James Harden’s current two-year contract with the Philadelphia 76ers is worth. I can’t tell if that makes Wonder’s deal look more or less impressive, so into the footnotes this mathematical coincidence goes.

Watching this documentary along with a number of interviews with Wonder throughout the years I was truck by how laidback and goofy Wonder is with his engineers and how stiff and unnatural he sounds when talking to journalists or speaking at award shows. I get the impression that Wonder is a pretty weird/socially awkward dude who feels way more at home in the studio than on TV.