Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I am learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each of them as I go. Once I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 456 songs to go!

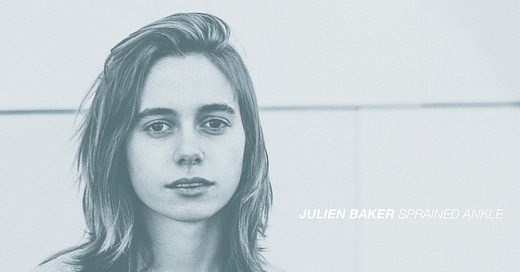

This week I learned “Vessels” by Julien Baker. Baker is likely best known as one third of boygenius, in addition to her successful solo career as a singer/songwriter. As it turns out, all three members of boygenius will show up in Drumming Upstream at least once. This will be the only Baker tune in the series, for reasons that will quickly become clear in the entry below.

Now, onto “Vessels”.

Side A

“Vessels”

By Julien Baker

Sprained Ankle

Released on October 23rd, 2015

Liked on December 15th, 2015

Some songs on my Liked list are songs that I’ve known and enjoyed for longer than Spotify has existed. Some were first encounters that have since aged into old favorites. Then there are songs that feel like the selection of a different person altogether, one trapped in a moment that has since passed. “Vessels”, the second to last song on Julien Baker’s debut album Sprained Ankle, belongs in the third category.

I was far from the only person to get swept up in Sprained Ankle fever in 2015. Baker first released the album, which she recorded independently while studying music engineering at college, on her personal Bandcamp page. Eventually it picked up enough steam to attract the attention of 6131 Records, who then signed Baker and rereleased Sprained Ankle. The sure bet paid off, the album roared across Tumblr timelines and blogrolls earning rabid enthusiasm from young fans. This earned in turn the attention of Merge Records, who snatched up Baker from the smaller 6131 and sent her on her path to selling out Brooklyn Steel for three nights in a row on stage with Phoebe Bridgers and Lucy Dacus. So of course as a self-respecting music writer I gave Sprained Ankle a listen, even if “indie” wasn’t my beat any more. I walked away impressed by “Vessels”. I loved the way Baker’s guitar sounded. I loved the empty space and how Baker’s perfectly calibrated delay hovers in the air by itself. I loved the dramatic rise and fall of the chord progression because I listened to a lot of post rock in high school. Good song, deserves a heart and gets one.

Though I told no one at the time, I walked away less than impressed with the rest of Sprained Ankle. I couldn’t even admit to myself that I didn’t like Sprained Ankle in 2015. If you checked the record of tweets, podcast appearances, and blog posts of the era I’m sure you’d find me speaking nothing but positively of Baker’s debut if I spoke about it at all. Unable to articulate my reservations, I got along to get along. Why was it that I couldn’t say what bothered me about the record? I can identify two reasons. First, I hadn’t listened to the album enough to put my finger on the problem. I hadn’t listened to the album enough because I didn’t enjoy doing so. Second, the conversation around Julien Baker framed her work with such high stakes that pointing out her music’s shortcomings read as a callous dismissal of real suffering. The first problem is a matter of Sprained Ankle’s music, the second problem is a matter of Baker’s lyrics.

Baker belongs to an American tradition of openly religious emo. In a video interview while touring on Sprained Ankle Baker names Sunny Day Real Estate, David Bazan1, and mewithoutYou as key influences, all three acts that played to emo crowds and sang to a much loftier audience. In particular she cites the way mewithoutYou "cut away the pretensions of songwriting". It is a telling compliment. Baker performs the same reduction on her own influences, stripping the genre's sonic bombast down to only her guitar and her voice. Sprained Ankle is emo performed with art house spareness.

Appropriate to this solemn tone, Baker aims her lyrical eye at both the almighty and her own shortcomings with linked intensity. Baker writes about herself at her lowest, a drug addict in recovery as seemingly unloveable in her personal relationships as she is in her relationship with God. In some cases Baker blurs the line between the two, like on the closing track “Go Home” which pulls a double meaning from its title. Elsewhere, like on “Vessels”, she cuts to the spiritual chase. In a record full of gruesome details about self-destruction, “Vessels” stands out for framing annihilation in purely religious terms. Here the “black ink” under Baker’s skin serves as both the vessel for the destruction of her earthly form and the proof of her imperfection and unworthiness. The only hope comes in the final lines, sung over a steadily ascending melody, when Baker affirms her body as merely its own vessel for an immortal soul saved by Christ. Heavy shit, and Baker’s writing lives up to the task of carrying it on paper. Taken as a whole, the lyrics on Sprained Ankle might suffer from overusing certain phrases (“black ink” and “blue” as heroin descriptors get a lot of burn on this record) and the youthful melodrama endemic to emo, but no one could accuse Baker of not taking her subject seriously or failing to draw larger themes out of her otherwise diaristic approach.

Unfortunately, the crimes of repetition and melodrama deal a fatal blow to Baker’s musical presentation. Despite its sparse arrangements, Sprained Ankle desperately lacks negative space. With the exception of “Vessels” the songs on Sprained Ankle plod unceasingly one eight note at a time from beginning to end. Making matters worse, Baker favors simple four chord patterns that often loop unchanged throughout the whole song. These progressions usually orbit around a few common tones, which makes it easy for Baker to hammer away at a handful of notes that work over each chord in the pattern. The notes Baker picks all feel emotional, but she sticks to those sweet spots so resolutely that they quickly turn sour from overexposure. Without variations in rhythm and harmony, and without melodies that travel in distinct arcs, the only thing uncertain 10 seconds into any track is whether Baker will switch from her “bananas and avocados” whisper to a full throated belt by the song’s end. Baker’s lyrics flatline against this static and shapeless backdrop until all that’s left is the vague appearance of emotional expression.

Appearance has been enough for many of my fellow critics. Jonathan Bannister unintentionally put it best in his review of Sprained Ankle for Post-Trash when he wrote that “the album has a feeling of authenticity to it” (emphasis mine). Even if it made her songs worse, Sprained Ankle’s minimalism read as a badge of realness, a signifier of her honesty, vulnerability, and intimacy. “There's no frills, no glossy production techniques, just an artist speaking the god-honest truth of their experience” wrote Hybrid Records in 2021, implying that complicating Baker’s songs with any dynamics at all would lessen the veracity of Baker’s experiences. Criticism of the presentation of her lyrics is tantamount in this framing to criticism of Baker herself. Under this rubric, Sprained Ankle isn’t valuable as an aesthetic or poetic experience, only as an object of parasocial sympathy. “I’ve never met Julien Baker” wrote wrote Jeremy Levine for Albumism in 2020, “but I hear someone I care about, someone who I want to befriend, who I want to be safe.”

This mode of criticism is fundamentally anti-music. Levine says as much himself, informing the reader that “you have to feel these songs as expressions of [Baker’s] humanity, not just things you listen to”. How does one feel a song if not by listening to it? All music is an expression of its creator’s humanity, and if we take their humanity seriously then we must also take the way they express themselves seriously. Regardless of how you feel about the way Baker expresses herself, reducing her choices to unfiltered feeling robs her of her agency as an artist. I may find Baker’s arrangement choices lazy and manipulative, but at least I acknowledge that she made decisions about her art and executed them. That might sound harsh, but listen to Baker’s most recent solo album Little Oblivions and you’ll see what I mean. Baker is clearly capable of fleshing her songs out with dynamic arrangements, which means that the minimalism on Sprained Ankle was a deliberate creative decision. To ignore that decision-making reduces art to a matter of who can demonstrate the most pain with as little obstruction as possible. The particulars of an artist’s craft matter less than whether they can suffer loudly and legibly to sate an audience bloodthirsty for “realness”. No wonder so many people think bands should sleep in the van.

I reject this view outright. Music isn’t just a vessel. It is beautiful unto itself. Let’s not annihilate it on the haphazard faith that something more pure is buried underneath.

Side B

“Vessels”

Performed by Julien Baker

60 BPM

Time Signatures: 3/4, 4/4

Whoa, check it out! A new section in the Side B header. Up until this point, every song that I’ve learned for Drumming Upstream has been in common time. This means that the rhythmic grid under the song can be evenly broken up into groups of four. As you may gather from the phrase “common time” and it’s ubiquity in the songs I’ve covered so far, 4/4 is practically the default time signature for western popular music. However plenty of other time signatures exist, and in some areas of the world these “uncommon” counts are as central to musical culture as 4/4 is in these parts. One of the most popular alternatives to 4/4 is 3/4. “Happy Birthday” for example, is in 3/4, as is any waltz by definition. If a song you’re familiar with isn’t in 4/4 there’s a good chance that it is in 3/4. Count along to your favorite tunes and I’m sure you’ll find plenty of examples. A song doesn’t need to be in a single time signature from start to finish. Some songs change from one time signature to another, others move through a gauntlet of shifting time signatures. Some songs even have multiple time signatures ticking simultaneously. The options are endless. We’ll have occasion to discuss all sorts of time signatures in this series, but for today we only need to concern ourselves with 4/4 and 3/4.

For the verses of “Vessels”, Baker alternates between 3/4 and 4/4. The measures of 3/4 are where the melody happens, rising and falling with Baker’s lyrics, while the measures of 4/4 are mostly open space. Then, for the instrumental bridge between verses she evens out to a steady 4/4. After the endless march of 8th notes in the songs preceding “Vessels” on Sprained Ankle, that extra beat of silence hits extra hard. Shifting back and forth between the two time signatures makes the song feel like it’s dissipating into the air, evoking the transcendence that Baker’s lyrics long for on a musical level. It is in my view unlikely that Baker wrote “Vessels” with numbers in mind. Nothing about the song calls attention to its shifting rhythm. The change in meter is a consequence of Baker writing melody-first. It doesn’t register as math when she changes the count, it just feels like breathing. It also, subtly, makes the bridge feel like a release from the tension of an uneven count, even though Baker executes the back-and-forth between 3/4 and 4/4 with a feather light touch.

I’m spending this much time on time because there isn’t much to say about the drum part on “Vessels”. Honestly, I had “Vessels” filed as one of the drumless songs on my Liked list for months until I started researching it while my snare was broken last summer. Turns out if you listen closely there’s a floor tom rumbling under the guitar in the bridge. If you crank the volume and listen closely again, you’ll hear a faint back beat pulse in the 4/4 bars of the verse. To this day, even after recording my own drums along with the song, I am unsure if Baker is playing all the way through in both verses. I’m pretty sure the part is consistent, but there’s a good chance that I’ve reached a point of Hackman-like delusion by now.

For this performance I planned on using two mallets, which give the floor tom a rounder, more orchestral tone. Sadly one of my mallets went missing on the day I planned to shoot this video, so I had to replace it with a regular stick. Oh well. I committed to what I perceived to be the backbeat during the verses. Better safe than sorry, I figured. To record a drum cover of “Vessels” at all is to overstate the presence of drums on this track. Better to commit to the part than sound hesitant. From there, the trick was finding the right amount of restraint and just the right urgency to keep the rhythm insistent without overpowering the rest of the instruments. I took the same reserved approach to my wardrobe for this video, pulling out a static grey button up that matched the glum winter mood that “Vessels” has a habit of putting me in. Uh oh, have I already given away where the song sits on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard? Find out below.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

Since this song was hoisted upon me by Ian circa 2015, I’m going to judge “Vessels” in a way that his Grantland-addled brain will understand. You see, boygenius are kinda like the 2012 Miami Heat led by LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Chris Bosh. Three superstars, all capable of commanding a team on their own, joining forces in hopes of winning a championship. Each of the three singers in boygenius achieved success as a solo artist, but working together their profile rose exponentially. And like the Heatles each musician in the trio brought their own unique identity and baggage to the stage. Which singer corresponds to which baller, you may ask? After years of careful consideration I’m prepared to give you one piece of the puzzle.

Consider that before boygenius Julien Baker was the second most well known member of the trio. Consider how much is made of her recording Sprained Ankle by herself, delivering a star making performance that singlehandedly put her on the map. Consider how much of that star-making performance boils down to Baker repeatedly spamming a few cheap musical tricks over and over again, appealing to the sympathy of an outside party to earn her points. There can only be one outcome: Julien Baker is the Dwyane Wade of boygenius.

I do not like “Vessels” very much, and I like Sprained Ankle even less. Maybe it’s just cause I'm a godless heathen, but all of the talk about destroying the self in search of supernatural bliss leaves a sour taste in my mouth. At least Baker faces the consequences of this self-annihilation with clear eyes, which is more than can be said of Washed Out’s heavy lidded gaze into the abyss on “Weightless”.

In the next entry of Drumming Upstream we’ll cover a song that I continue to enjoy to this day, from the series’s first repeat artist and a master of the so-called pretensions of songwriting. Until then, I hope you have a nice week.

I’m shocked that Pedro The Lion’s “Second Best” isn’t on my Liked list. That song rules. I’d have so much more fun writing about that song instead of this one. Damn.