It is time to return to Drumming Upstream. We’re now 6 songs deep into my Spotify Liked list, only 476 to go! The preceding songs haven’t been particularly challenging to learn or perform. This entry however, was a leap in difficulty both on a practical and conceptual level even though on paper the drum part is quite simple. How can that be the case? Let’s find out!

But first: a confession.

The Dead Pig In The Room (or, “I Was A Scott Walker Poser”)

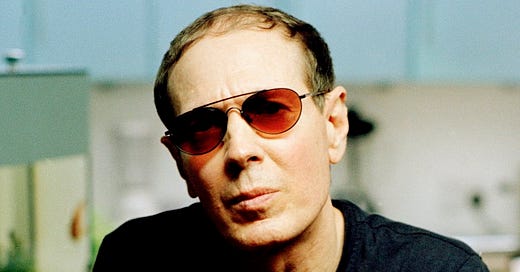

Scott Walker, former boy-band crooner turned enigmatic avant-garde recluse. Scott Walker, purported possessor of Godlike Genius. Scott Walker, haver by coincidence of an unfortunate name. Scott Walker, erstwhile performer of Jacques Briel songs, now deceased recordist of punched pig meat. Born Noel Scott Engel in Hamilton, Ohio, Walker found fame in England in the mid 1960s as one of The Walkers Brothers. After a few albums of inoffensive baritone-led ballads, Walker went solo. Over the course of four self-titled albums Walker’s music got increasingly weird in increasingly severe gradations. In the 1970s he put out a string of albums that zero people talk about, so I’m not going to talk about them either. Then he retreated from public life and released only five albums in four decades until his death in 2019. It is on those five albums that the weirdness gradation went from steep to exponential. Again, we’re talking about a guy who went from “The Sun Ain’t Gone To Shine No More” to perfectionist direction over dead pig pugilism. Before I even heard a note of Walker’s music, I was hooked on his myth alone. The path from pop music heartthrob to hellishly strange, serious artist was an inversion of the common story of an artist’s success corrupting their work. Here was a guy that tasted fame and fortune and gave it the finger in favor of doing whatever the hell he wanted. Walker didn’t sell out or buy in, he returned the check with no signature. His very existence and the continued vitality of his work was a victory of art over commerce.

I didn’t reach this conclusion about Walker’s coolness alone, of course. When Walker’s 2006 album The Drift came out, the music press treated it with the awe and superstition of a passing comet. Everyone that liked his music seemed to my teenage eyes and ears like the smartest people around. Pitchfork gave it a 9. Even if I pretended to be too cool for Pitchfork at that age I knew that meant serious business. 16 year old Ian would have let Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt throw my TV out the window and dump my unabridged copy of Romance Of The Three Kingdoms into the Gowanus canal with a smile on my face, so taken was I by their. combination of death metal and progressive rock1. Mikael Åkerfeldt talked about Scott Walker the way I talked about Mikael Åkerfeldt. I had no choice the matter, I had to become a Scott Walker fan.

I dutifully downloaded The Drift. To this day I can recall its rusted-metal-red album cover clashing against the off-white of the iTunes library. I can recall feeling uneasy and confused in what seemed like a sophisticated and grown up way while listening to it. I remember downloading Tilt not too long after, marveling at the swirling darkness of its cover. I remember watching Scott Walker: 30 Century Man on Netflix and retaining an impression of Walker as a surprisingly down to earth and humble guy. I remember eagerly signing up to review Soused, Walker’s unexpected collaboration with drone metal duo Sunn O))), for the website Unrecorded at the earliest opportunity. What I cannot remember is a single note of music from The Drift. I haven’t listened to The Drift, Bish Bosch or Soused in years. Until I started working on “Bolivia ‘95” for this project I don’t think I’d listened to Tilt since October 2014. I’d listened to the Scott quadrilogy in full only once, just to know the context for Walker’s later material. All this time if you’d asked me what I’d thought of Walker’s music I would have told you that I loved it and prayed that you didn’t ask any follow up questions.

Now, in my defense, I don’t believe that someone has to listen to a piece of music frequently in order to claim to love it. I mean, hell, Scott Walker himself claimed to only listen to Tilt in full once upon completion and he liked it enough to put his name on it. Measuring a listener’s feelings towards a piece of music by their play count, as Spotify does yearly with Spotify Wrapped2, ignores the depth of the experience the listener might have with the music. I’ve watched the viral clip “I Can’t Believe You’ve Done This” more frequently than Mulholland Drive by a power of ten, but that doesn’t mean that I prefer it over David Lynch’s best movie. I’ve eaten more french fries than steaks, but all that means is that french fries are easier to prepare and eat in large numbers than steaks are. Favoritism does not follow from frequency, and Scott Walker is a cooker of steaks not french fries.

But ok, yes, I’ll admit it, I am a Scott Walker poser. That much is mathematically certain. The question that remains is why. Why did I want to think of myself as a Scott Walker fan, and why did I want other people to think of me as one? Why did I want this status so badly that I’d even Like a Scott Walker song on Spotify and then never listen to it again? It is one thing to be a fan of the myth of a pop star gone rogue. It is another to profess admiration for the man’s music without being able to back it up with anything deeper than Hansel’s praise of Sting in Zoolander. The ugly truth of the matter is that it feels good to think of myself as someone who “gets” difficult art. I don’t like being made to feel dumb, generally. So when a challenging work of some prickly genius steps to me like I can’t handle what it’s putting down I’m liable to get a bit toxically masculine and invite it to come at me, bro. This is how I end up referencing Gravity’s Rainbow in every other newsletter, or playing Dark Souls and reading Moby-Dick at the same time. Mama don’t let your babies grow up to be gifted students, etc. Of course, I do genuinely love Pynchon, Lynch et al but only because I got past thinking of them as Difficult Artists and started engaging with the actual content of their work. The same can not be said for my approach to Scott Walker.

Until now.

In preparation for this cover I’ve listened to the whole Scott Walker catalog. Well again, I skipped the 70s stuff, but I listened to all of the Scott Walker albums that matter. Guess what? They’re great! Snatches of The Drift even rang a cathedral’s worth of bells in my memory’s town square. I’ve listened to “Bolivia ‘95” in particular A LOT. I’ve done more takes, completed and abandoned out of frustration, of “Bolivia ‘95” than the rest of the songs in the series so far combined. If I don’t listen to “Bolivia ‘95” again for another eight years, it won’t be out of disinterest. It will be to give myself a break. Luckily I have the rest of Walker’s songs to listen to instead, for “Bolivia ‘95” has wiped me clean of my poserdom and rendered me a real fan. Let me explain how.

Side A

“Bolivia ‘95”

By Scott Walker

Tilt

Released on May 8th, 1995

Liked on October 14th, 2014

If we accept the premise that Scott Walker’s later period’s reputation of difficulty is well earned, what can “Bolivia ‘95” tell us about why it is difficult? Why do people find it to be so strange? One explanation might be that people find it strange because of how much it differs from the records Walker released in his youth. That’s worth considering. But I’d bet that most of the people who pressed play on the video above wouldn’t describe “Bolivia ‘95” as a standard issue pop song even if they hadn’t heard The Walker Brothers before. (I guess I kinda spoiled that for some potential readers by hyperlinking to the The Walker Brothers earlier. Oops). What makes “Bolivia ‘95” weird even to the newest of newcomers?

“Bolivia ‘95” is the second track on the second side of Tilt, or the sixth track of nine on the CD version. Scott Walker released the retroactively aptly named Tilt in 1995, just a handful of years after the halfway point in his five decade long solo career. Doubly situated just after the midway point of the midway point of Walker’s discography, “Bolivia ‘95” offers us as ideal an example of Walker’s style tipping over from early-and-accessible to late-and-difficult as we’re likely to find. I had no way of knowing this, having at the time no idea of when Walker, then living, would stop releasing music, when I Liked the song in 2014. All I knew was that the sound of Walker’s singing “babalú”at 3:54 (just over halfway through the song, I might add) was beautiful, if eerily so, in a way that caught me by surprise. My introduction to Walker was The Drift, and that album led me to believe that moments of genuine beauty in Walker’s late period were as rare as new releases from the man. Eight years later, this moment of unexpected beauty flickers like a candle in darkness, shining light on the conventional parts of “Bolivia ‘95” in contrast to the yet indistinct strangeness surrounding them. By determining which elements of “Bolivia ‘95” are normal, we can identify the source of its uncanniness by a process of elimination.

Walker’s voice is a good place to start. There is no Scott Walker album where Walker’s voice, taken as a standalone instrument, does not sound beautiful. Despite claiming that he got up to “a whole lot of drinking” in his years away from the public eye Walker sings like nothing harder than seltzer has ever graced his throat. On the records that followed Tilt, Walker would try and disguise the resonant smoothness of his baritone by inter-splicing it with shouting, bizarre duck voices, or non-melodic mouth sounds, but no matter how hard he tried to hide it, the ghost of his past as a pretty-boy crooner made its way into every note he sang. When people talk about finding music difficult sometimes they’ll describe it as being “hard to follow.” But “Bolivia ‘95” is pretty conventionally laid out. The song’s length might fool you into thinking otherwise, but “Bolivia ‘95” is a verse-chorus affair. It doesn’t even bother with the complication of a bridge, although if you feel like the irony-tinged-boisterous second verse that inspired me to Like the song to begin with differs enough from the first and third to qualify as its own section, I wouldn’t argue with you about it.

If it isn’t the tune’s lead instrument or its structure that are putting people off, the answer must lie somewhere in between. It must be what fills the contents of its form and surrounds Walker’s voice that makes “Bolivia ‘95” feel so strange. Here, the previously mentioned speculation about the contrast between Walker’s early records and Tilt becomes useful both practically and metaphorically. On the Scott quadrilogy, Walker’s voice is the eye of a storm of strings. Although you can hear the figurative spotlight on Walker, the small army of musicians behind the bandstand is still close enough to catch its reflections on their cufflinks. By contrast, Walker’s voice on “Bolivia ‘95” is surrounded mostly by silence. His band, now reduced to a rock arrangement with a few auxiliary percussionists, are set so far back into the shadows of the song as to be practically invisible. The silence is so pervasive that it even invades the space between sections of the song, helping contribute to the intimidating length that hides its traditional structure. It is no wonder that first time listeners with no road map would find themselves lost in the negative space between notes, unmoored, ungrounded and uncertain.

This answer only provokes another question: why would Scott Walker arrange “Bolivia ‘95” this way? We can’t ask the man himself anymore, but luckily for us Walker made a point to mention in every interview that I listened to3 as research for this entry that he always begins his songs with lyrics first and then “dresses” them with his instrumental choices. If we want to know why “Bolivia ‘95” sounds the way it does we need to start from the words. Let me tell you, I’ve been dreading tackling this song’s lyrics. You put a South American country and a specific year in front of me and this anxious yanqui will start getting really concerned with all of the world history he doesn’t know anything about. The editors at Wikipedia seem perplexed themselves, since their explanation of the song’s topic puts a lot of weight on the word “apparently” and ends with no citation. Luckily, Walker doesn’t make it too hard to suss out what he’s talking about.

Walker, or more accurately the character he’s singing as, begins by asking for “a C” so that he can sing a “babalú,” anglicized on Genius dot com as “Babaloo.” Older readers might recognize this word from a song that Desi Arnez used to sing on the TV show I Love Lucy. The song Arnez sang is older still, dating back to 1939, and is a prayer for good luck from Babalú-Aye, a deity of both sickness and health in the Afro-Cuban religion of Santeriá.

Now, I don’t practice Santeriá. I don’t have a crystal ball either (and don’t get me started on what *I’d* do with a million dollars). I do, however, have an internet connection, which informs me that Babalú-Aye is an exile, forced to leave his hometown over his having spread a plague there. It isn’t a stretch then that Walker’s narrator might not just be praying with good health in mind. Maybe that line on the Tilt wikipedia page about “Bolivia ‘95” “apparently” being about migrants wasn’t just a shot in the dark.

With this in mind, the rest of Walker’s lyrics begin to open up. His narrator “journeys each night like a saint/to rest on this straw floor” wearing loose and flimsy “uniforms”. The reason for this beleaguered escape? A haunting blues refrain of “lemon bloody cola.” In 1995 the Bolivian government, encouraged by the United States, was in the process of eradicating the coca plant from Bolivian farms. The coca plant, as I’m sure you know, is an ingredient in both the soft drink cola and the other kind of coke. Walker doesn’t make it clear whether his character left home to escape violence from the cartels or from the government crackdown on the farmers that organized against the eradication, but the “¡Manos Arriba!” in the first verse suggests a threat from someone working with at least the pretense of due process. What matters is that the road is hard and our narrator could use something to ease the pain in the darkness of night.

In this light, or lack there of, is it any wonder that the arrangement of “Bolivia ‘95” sounds so inhospitable? It is worth pointing out that the non-rock instruments on the song like the flute in the song’s intro and the stuttering string sound at the end of the track aren’t of Bolivian origin. The former is a bawu, a Chinese bamboo flute, and the latter is a cimbalom, which is a Hungarian variety of the dulcimer. Every part of the song is rootless in an ocean of silence.

The reason people find Walker’s music difficult is that it asks them to listen to it words first. Without a lyric sheet in front of you, all of his arrangement choices have no context and are easy to write off as weird for the sake of weird. The funny thing about approaching music with the preconception that it will be hard to understand is that this assumption only makes it harder to make sense of the music you’re hearing. When I said that “Bolivia ‘95” made me a “real Scott Walker fan” what I meant was that the song taught me by example how to listen to the rest of his music. For years I bounced off of his records because I was so assured that I would not “get it” that I never bothered to see if there was anything to get. Now I know where to look.

Looking and listening is one thing, but knowing a song well enough to play it is a whole other collection of worms. Let’s flip this baby over to Side B to see how well I did when it came to opening that can.

Side B

“Bolivia ‘95”

Performed by Ian Thomas

87 bpm (approx)

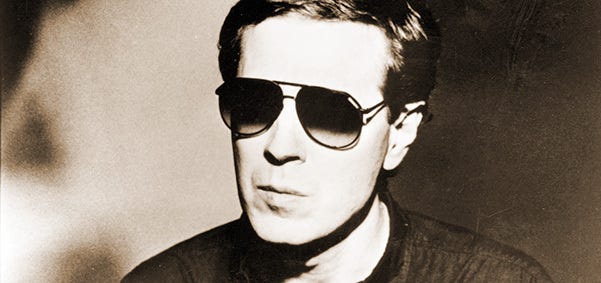

First, let me introduce you my fellow Ian and the drummer on “Bolivia ‘95”, Ian Thomas. Thomas is not a musician that I bet many know by name or even by sound. But session musicians like Thomas hang just out of focus behind the biggest stars in the business. In addition to Scott Walker, Thomas has played with George Michael, Seal, Eric Clapton, BB King, Van Morrison, and Celine Dion. He is, in other words, the real deal.

I try and take every song I learn in this project seriously, but I won’t lie that after looking at Thomas’s resume I sat up straighter in my seat. The part that Thomas plays on “Bolivia ‘95” isn’t busy or physically demanding, that wouldn’t fit with the song’s starkness, but every note that he played is there for a reason. Every time I’d finish a nearly right take I’d summon up that image of Walker in the control room stopping a recording to correct someone’s manual pork tenderizing, sigh, and give Thomas’s part another listen. Even now there are still minor flubs that I wish I could iron out. But with time at a premium, I give you my overall best performance of “Bolivia ‘95”:

Part of the reason that Thomas’ playing was tricky to emulate is that he isn’t playing to a click track. Even a drummer as decorated as Thomas is going to slip and slide a little tempo-wise, especially when there’s so little else in the arrangement to play off of. The song is filled with so much negative space that the slightest discrepancy between my timing and Thomas’s sticks out like a sore thumb. I can’t tell you how many times I’d make it to the final snare-smacking chorus only to miss a bass drum hit with nothing to cover up my negligence. There go seven more minutes of my life.

This lack of a safety net made the extra-sparse first and third verses a real bear to figure out. First, I had to determine what parts I should I even play. Should I emulate the jangling percussion with my hi-hat? What about all of the percussion hits that pop up around Walker’s voice? In the end I decided to stick to the instruments that were most obviously part of the drum kit, which is what Thomas is credited with performing on the song. With my workload thus lightened I focused on following Thomas’s press rolls and cymbal accents, as well as tom hits that serve as the punctuation at the end of each phrase. This is where my warmed-up musical theater chops came in handy. With no grid to lock into I kept track of where I was in the measure by playing of off Walker himself, and by listening for a cue from the bass guitar. In each phrase of the verse bassist John Giblin plays three “ba-BUM” accents before synching up with Thomas’ tom fills to end the phrase. It took me a while to find this cue because the only exception to this rule is the second phrase of the first verse, i.e. the earliest opportunity to spot a pattern. Thanks, John.

My week playing the music of Chicago also helped tighten up my press rolls, a technique that eluded me in the past. Press rolls are one of the rare techniques on drums that abandon the grid of subdivisions for a smear of pure sound. I did my best to match the shape of Thomas’s rolls but at a certain point I had to back off and just do my own thing. Could I have spent another week nailing down every single improvisatory stroke that Thomas made? Sure, but time was ticking and I had to ask myself whether it was more important to learn the song or learn the recording. I’d like to think that I could, if asked, record a version of the drum part that achieves the same end as Thomas’s performance even if it isn’t note-for-note, nanosecond-by-nanosecond exactly the same as his final take. But really only one person can say for sure whether that’s true, and he ain’t around anymore.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

So with my ears opened to the true form of Scott Walker’s music and with my muscle memory finely tuned to recall each twist and turn of “Bolivia ‘95”, where does the song sit on the on-going ranking of the best songs on Spotify according to yours truly? As a work of high-level session musicianship and songwriterly expression it easily glides by Joyce Manor’s “Constant Headache”. But if I’m honest with myself, now that I’m free of my self-imposed Walker-posing I can admit that “Bolivia ‘95” impresses me more than it moves me, either physically or emotionally. For now it will sit beneath the booty-shaking “Body & Blood” as well as the heart-string pulling tracks in the top three.

“Bolivia ‘95” by Scott Walker

If you, like me, are looking for something a bit less intellectually stimulating and dance floor appropriate, you’re in luck. The next entry in Drumming Upstream sends us straight to the discotheque. Thanks for reading, and see you there.

Opeth will show up later in this series. Not looking forward to the double bass drills that learning their tunes will require.

Incidentally, I am looking forward to seeing what a year of working on Drumming Upstream has done to my Spotify Wrapped stats. It will be clear which songs took the most work by how prominently they sit on Spotify’s version of the leaderboard.

Listened to as opposed to read because Walker’s speaking voice was just as easy on the ears as his singing.