Welcome back to Drumming Upstream! If this is your first time reading this series, I am ten songs deep into learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each of them. After this song is finished I only have 470 left to learn. Exciting!

Isis, the decade-long defunct Los Angeles-by-way-of-Boston metal band at the center of today’s letter, will show up many times in Drumming Upstream. In fact, each of their full length albums will have a representative in this series with one track from a compilation thrown in for good measure. I can think of few other bands that have had as big of an impact on my own artistic practice as Isis, and few other drummers that I’ve tried to emulate with more frequency than Aaron Harris. The band’s vaunted status in my personal canon made learning “Carry” on drums pretty easy, I’d played along to the song many times before I’d conceived of this project, but has made writing about the song troublesome. How can I say something new, to myself or to the world, about a song that I’ve lived with for over half my life?

Well, here’s my best shot.

On Side A I’ll address my personal history with the song as well as the themes and aesthetics of the album Oceanic. Then on Side B I’ll dig into the granular details of Aaron Harris’s drum performance and the twist and turns of “Carry”’s linear structure.

Side A

“Carry”

By Isis

Oceanic

Released on September 17th, 2002

Liked on November 18th, 2015

I knew that I loved “Carry” a decade before I Liked it. I knew that I would love “Carry” even longer than that, though not by much. Long before it circulated around a very different corner of the internet and carried a far more troubling connotation, the name Isis called to me from the depths of music forums and from the back pages of webcomics. Older metal heads the world over spoke of them reverently and pointed to them as the next step for a young dirtbag looking to slide deeper into challenging music. Questionable Content, a webcomic about the love lives of Bostonian hipsters, prominently featured their second album Oceanic as one of only two metal albums1 on its recommendations page, describing Isis as half-way between Slayer and Godspeed You! Black Emperor. This was years before I could verify the comparison without buying a CD myself, so Isis grew to totemic proportions in my imagination. When summer rolled around and my parents asked what I wanted for my 15th birthday I asked for Oceanic assured that I had a new favorite album on the way.

It was a listless summer. In July I shipped off to an arts camp I had attended the previous summer. That first year at camp had been a blast. I made friends, felt feelings, and soaked up a beach towel’s worth of new music from my fellow campers. The second time around I hardly felt the need to meet anyone or go anywhere. In the span of a year my interest in drumming had begun to verge on monomania. Away from my kit for two weeks the best I could muster was a mechanical routine of “wake up, eat, wander over to the camp radio station, sit and do nothing, eat, do nothing, eat, sleep.” The only breaks from the monotony came from the rare sight of two older French girls that attended the camp that year whose mere passing boiled boy’s brains in their skulls. Nothing else warranted more than a flatline.

I had a companion in this teenage ennui, another musician and mp3 hoarder. During our shared stretches of doing nothing we’d pass the time by showing each other music. One day at the radio station he passed me his iPod and let me go nuts. It didn’t take long until I’d rolled the wheel onto the four letters I-S-I-S. I got half way through one song before a rare obligation whisked the Beavis to my Butt-Head away along with his iPod and Isis. What I had heard bewildered me and excited me in equal measure. Every second between me and my escape from the doldrums to the real drums that awaited me in Brooklyn passed with all the more agonizing sluggishness knowing that an Isis album awaited me as well.

The New York City I returned to was a thick soup of heat and humidity. It was the kind of summer that reminds you that yes, Brooklyn is on an island. The ocean has you surrounded, and when it gets this hot it presses the advantage. The streets are wet. Passing through the air takes longer than it should, like you’re walking along the floor of a public pool. In this sweltering sweatscape the line between your perspiration and the moist density of the world starts to feel about as sturdy as damp paper. It was in that porous inferno that I first heard “Carry”. At the time two Swedish models were staying with us at my parents’ apartment (long story), theoretically every straight 15 year old boy’s dream. In practice I found their presence terrifying. I was convinced that if I made direct eye contact with either of them my flesh would melt right off of my bones, so every morning I would hole up in my bedroom with the curtains drawn until they had left the apartment. Curled up in bed with the summer sun drenching my room in a yellow haze through the membrane of the curtains, I would listen to Oceanic on repeat and let my mind drift off to sea.

Oceanic, released in 2002 through Ipecac records, is Isis’s second full length album and second collaboration with producer Matt Bayles. For their previous album Celestial and the shorter releases that proceeded that debut, Isis worked on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. The band emerged like Cave In and Converge2 from the Boston art school scene. Isis, however, were not a hardcore band. Instead, following cues from acts like Neurosis and Godflesh, Isis took the aggressive roar of metal and hardcore and stretched it into a slow mechanical churn. Their music was just as punishingly loud as the macho Mass-hole “haahdcore” bands in their general vicinity, but Isis moved that sonic weight patiently, methodically, and with each new release increasingly hypnotically. By the time they began working on Oceanic the expanse of their sound had outgrown their eastern horizons. For the album’s recording sessions they decamped to Los Angeles and the greater vastness of the Pacific.

Isis weren’t the only band turning seaward in the early 2000s. Indie rock was still bobbing in the wake of Neutral Milk Hotel and happily lapped up nasal sea shanties from bands like The Decemberists. Metal on the other hand was two years away from Mastodon’s Moby-Dick inspired Leviathan and the debut of the marine biology themed Giant Squid. Unlike those bands Isis didn’t see the ocean as a setting or a subject to be conquered or studied. Instead they depicted the sea as a source of sublime negation, a force of unimaginable destructive power with an intoxicating allure. Oceanic tells the story of a man who, upon learning that the object of his affection is engaging in an incestuous affair with her brother, leaps into the sea to his death. He isn’t just driven to the ocean by despair, he is seduced by the oblivion that it offers.

Isis don’t make it easy to follow this arc by ear. Singer, guitarist, and graphic designer Aaron Turner delivers his lyrics in an ursine howl made all the more inscrutable by its low placement in the mix. Maria Christopher of the trip-hop flavored indie band 27, Turner’s duet partner on “Carry” singing from the perspective of the sea, is no easier to make out. To catch the album’s drift I had to open its foam green liner notes and piece together Turner’s lyrics in real time with the music.

Both “Carry”’s lyrics and its music begin with a prolonged ellipses. Isis spend the first four minutes of the song crawling out of a primordial ooze provided by keyboardist Bryant Clifford Meyer. Jeff Caxide’s bass emerges first, followed by Harris’s drumming and finally Turner and Mike Gallagher’s guitars. With the entrance of each new instrument the haze of the song’s first moments recede into the distance like a tide pulling out to reveal a hidden land mass. After patiently building on each other’s parts, Isis unleash the sea’s full power back onto the shores. As wave upon wave of distorted guitars crash against the listener Turner describes how the water “fills his lungs and crushes his body”. Even as he is annihilated he hears a voice calling to him sweetly from the depths. “Fall to me,” Christopher whispers from beneath the maelstrom of the song’s surface “I will carry you, true and free.”

What Turner evokes here in both his lyrics and his band’s music isn’t just death but a kind of sublimation. Under the water his protagonist loses track of where he begins and the ocean ends. Lines are blurred in every direction. The song’s melody shifts from one guitar to the other and then to Christopher’s ghostly voice. Once Isis enter the song’s final stretch making sense of which sounds are guitars and which are keys becomes a fool’s errand. The ambiguity is the point. Is the voice the protagonist hears the ocean’s or is he haunted by the one-time object of his affection? Is he dissolving into a new lover’s arms, or he is returning to a watery womb? From their name down, Isis have always had a thing for the divine feminine. Their first EPs and some of Celestial framed this interest from the perspective of insect hives worshiping their almighty queen. Oceanic goes further and devotes itself to the aquatic mother of all life on earth3. Without ever putting too fine a point on it, Turner’s lyrics draw a connection between the desire to lose yourself in another person, the desire to cease to be at all, and desire to return to The First Other.4

By age 15 I had heard plenty of metal songs about death and dying. I’d also heard, by dint of being alive and possessing functional ears, plenty of songs about sex. I had not heard anything quite like “Carry”. The few metal albums I’d heard that had even glanced at eroticism did so with the eyes of a cartoon wolf in a tux. Isis’s blend of thanatos and eros by contrast felt refined and mature. Everything about Isis seemed grown up to me. They kept their hair short, dressed in an unassuming style, and casually name dropped philosophers and literature in their interviews. I was intimidated by them, but also inspired. I had loved a lot of metal musicians before, but I never thought of any of them as role models. Isis were different. They looked the way I wanted to look, had read the books I wanted to read, and could write confidently about sex in a way that wasn’t gross or watered down. This was the future, I thought to myself. The future of heavy music, and my own. I wanted to be a part of whatever conversation this band was having with music history, at any cost.

Summer ended. The Swedish models left, presumably back to Sweden5. I emerged from my room with renewed focus. I had guessed right, Oceanic was my new favorite album. My monomania sharpened further. All I wanted was to play drums, and I wanted to play drums for music that sounded like Isis.

Side B

“Carry”

Performed by Aaron Harris

107-125 BPM

Devoted Drumming Upstream readers might notice a similarity between my interpretation of “Carry” and the previous entry on Washed Out’s “Weightless”. Those readers might be confused as to why I spoke so highly of today’s entry when I lambasted “Weightless”. The simple answer is that I prefer extremely loud guitars to pillowy synths. The complicated, and more satisfying answer is that it all comes down to structure. “Weightless” is essentially a loop, verse-prechorus-chorus and repeat. “Carry” on the other hand starts one place and ends somewhere very different. In “Weightless” oblivion is a static state of being. In “Carry” oblivion is something that happens to its protagonist, and Isis do their damndest to make you feel it on the other end of the speakers too. Isis don’t want to you to experience the dissolution of the self as a temporary vacation, they want you to feel the water crashing down on you before you get your sweet release.

So far all of the songs I’ve learned for this project have had a verse-chorus form, or at the very least have been propelled by two contrasting sections. “Carry” however does not work this way. Instead it moves linearly through a series of sections that never return in the song. I mentioned on Side A that it can be tough to pick out which instrument is playing which sound in “Carry”. That haziness also extends to the song’s structure. Until the distortion kicks in about two thirds through the song, it isn’t clear if Isis are moving through discrete sections or working out variations of a single part. The heavy final third appears just as murky at first glance. This apparent formlessness has turned a lot of people off of Isis’s music. When I brought up Isis to a metal fan I knew in college he scoffed and asked me “is that the band that just plays one riff for ten minutes?” That guy turned out to be a real asshole with bad taste, but even smarter writers like fellow newsletter-er Zachary Lipez dinged Isis and their contemporaries’ style as “a consolation prize for good hearted metal guys who can’t write a catchy riff”.

The accusation is a tough one to dismiss out of hand. Isis songs, especially from this part of their career, sound like the product of improvised jams that the band organized into songs after the fact. They aren’t big on choruses and most of their riffs focus more on size than on melody. However, “Carry” is far from formless or hookless. The hooks just aren’t where you’d expect them to be.

When I started learning “Carry” on drums, I carved the song into five smaller chunks. This served the practical purpose of making the song easier to learn part-by-part, but it also illuminated the song’s underlying logic. Here are the chunks that I came up with:

Drone Intro (0:00-0:46): This ambient intro acts as a bridge between the previous song on Oceanic and “Carry”. Though it sounds like it might be a synth pad, this part is actually half keys and half distorted bass. Right from the jump Isis are challenging your ears to make sense of what you’re hearing.

Gradual Build (0:46-2:34): After droning on one note, Jeff Caxide starts to play the song’s first real bassline. Harris, Gallagher, and Turner enter with their own parts in that order. When the drums kick in at 1:24, Meyer’s keyboard part starts to double the bassline in a higher octave. When Turner’s guitar comes in at the two minute mark Harris adds the snare and Gallagher switches to a new melody.

Light Groove (2:34-3:59): Gallagher’s melody carries over but otherwise everything changes. Harris locks into a full drum groove, Turner switches from playing textures to a developed counter melody and Meyer’s drone recedes all the way into the background. This section crests briefly when Harris moves to the ride cymbal and then settles back down before exploding into the next chunk

BIG LOUD (3:59-5:34): The distortion kicks in and Turner starts screaming his head off. This section is the payoff for all of the tension that the band have built up to this point. Everyone’s parts in this section are completely distinct from what they were playing up to this point. This is also the only section with Maria Christopher’s vocals. Hmm, where have I heard that melody before?

Climax/Coda (5:34-6:45): After pummeling you for a minute and a half, Turner and Gallagher turn off their distortion and the band switches to a new riff that, I don’t know, I think is pretty catchy! The relief is short lived, because the distortion roars back and stays there until the song ends.

Pretty far from “one riff for ten minutes.” Each of these chunks raises the intensity of the song in one way or another, either by adding instruments, changing dynamics, or shifting to completely new musical material. What jumped out to me when I laid the song out this way was how balanced each section was in proportion to each other. Once Caxide starts up the song’s bassline each section of the song lasts for about a minute and a half, with the build up taking slightly longer and the Coda wrapped up slightly faster. Even that discrepancy is balanced, the build has the extra 15 seconds that the Coda skimps on. Despite the whole of the song stretching way past a radio-friendly runtime, no individual part of the song overstays its welcome.

The further I dug into the song the more I realized that this overview was insufficient. Each section, again barring the intro, has a smaller structure of its own that rises and falls before the band move onto the next phase. Some of these smaller structures aren’t even linear! The “BIG LOUD” section for example is an ABA form of two similar but distinct riffs. More importantly, ideas from one section will crop up in the next one. The Light Groove ends by returning to the stripped down drum groove that Harris played in the intro, albeit at a more urgent tempo, and when Christopher starts singing in the next section her melody is the same as the one Gallagher outlined in the song’s softer side. The only part of the song that is unrelated to the parts that proceed it is the Coda, which is why that sudden drop in volume feels so dramatic.

The details get even more granular from here, but it might help for you to watch me play the song on drums in order to pick them out.

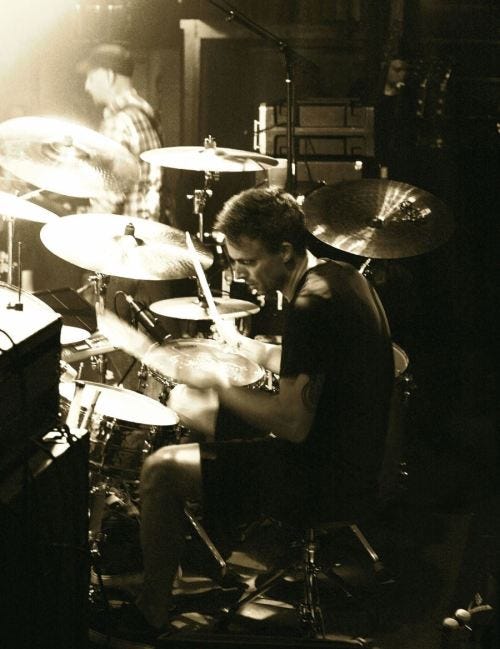

I guess before we talk about anything else, I should talk about the snare. The wires on my snare drum are busted, so instead of sounding like “KAH” my snare drum sounds like “BNG”. Gear breaking down is always a bummer, but in this case the sound kinda works. The snare drum on Oceanic is uh, unconventional. Usually the snare sound is all about the initial attack, the crack of the stick on the head of the drum. Harris’s snare has some of that, but it sounds far off like he’s hitting it in an empty stairwell at the end of the hall. I remember a lot of drummer’s speculating that Harris was playing with his snare off, when in fact Harris and Bayles achieved the sound through tuning, reverb, and Harris’s particular snare build-out. Making one of the most common sounds on your record this conspicuous is a bold choice, but it fits right in with the waterlogged mood of Oceanic.

Harris knows exactly how to make this roomy sound work. Every choice he makes on “Carry” is finely tuned to work with the drum sound he has, not just in the abstract. Notice how he pulses the volume of his hi-hats so that many of the softer notes fade into the mix of the song, or how his fills often leave a space before crashing into the next measure. Harris has decluttered his playing, so that the long tail of the notes he does play have time to breathe. He’s not just playing parts, he’s playing the instrument.

For a great example of Harris’s attention to detail, let’s look at how he handles the “BIG LOUD” section of “Carry”. As I mentioned before, this part of the song is a self-contained A-B-A form. We get one riff that repeats four times, then a variation that repeats four times, and finally the first riff for another four. The first two playthroughs of each riff are instrumental and the second two have vocals over them. Harris navigates all of this brilliantly. His part remains broadly the same over the whole section, but he makes minor changes to his fills to mark the differences. When the band reach riff B for example he switches his fills from the snare to his toms. He also makes a few minor changes to the groove, first for a pair of powerful accents at the start of riff B, and then by dropping the extra snare hit at the end the first measure when the band returns to riff A. None of this is rocket science, but all of these small choices add texture and form to the song. They make the drums catchy so that the riffs don’t have to be.

Finally, a note on the tempo. It’s honestly stunned me how few of the songs I’ve learned so far are click perfect. Every drum teacher I’ve ever had has drilled into my skull the importance of locking in with a metronome. I’ve beaten myself up over minor fluctuations in tempo when practicing and I’ve had engineers nit-pick my takes with the best of intentions for the same reason. And now I’ve learned that a lot of music that I love just… doesn’t give a shit about any of that. Even more baffling is that with the exception of “Constant Headache” I would have guessed that every single one of the songs I’d learned so far was recorded to a click. Still, if I had to guess, even if Harris didn’t record to a metronome I bet he practices to one. The tempo steadily increases over the course of the build from 107 bpm to 125 bpm when the BIG LOUD section kicks in. However, measure by measure Harris’s time is remarkably consistent. It doesn’t feel like the song is spiraling out of control so as much that Harris is shifting gears until the song’s climax is exactly where it needs to be. This is almost more impressive to me than locking into a grid and staying with it for the whole song.

Pulling back the curtain on “Carry”’s loose tempo has in no way disillusioned me however. I still love this song, and I loved playing it. To find out exactly how much I love it, join me in the next section for the DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

I must confess that until today this Leaderboard has been a sham. I haven’t deceived you about how I feel about any of the songs that I’ve learned and written about so far. I’ve tried to be as honest as I can in my assessment of all of them, for good or for ill. My deceit is a matter of scale. I like all kinds of music, and I’m proud of the well-rounded impression of my taste that the Leaderboard has presented so far. But I love heavy metal. It was only a matter of time until a metal band sauntered straight to the top of the list. I imagine Isis will stay there for quite some time.

“Carry” by Isis

Thank you for reading this especially hefty edition of Drumming Upstream. Since my snare drum is out of commission I might have to dip back into the drum-less songs in the Liked list. Might be nice to lighten the workload after the paces this letter put me through. See you next week!

The other was Opeth’s Blackwater Park. Opeth will come up in this series eventually, though given how difficult their drum parts are it might not be until we’re nearing the end of this exercise.

They’d take another stab at this divine feminine concept from a more post-modern angle two albums later on In The Absence of Truth, but we’re still a ways off from talking about that record.

Ask Me About My Neon Genesis Evangelion Podcast