Welcome back to Drumming Upstream! If this is your first time reading, my plan is to learn every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums, write about each of them, and then delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. As of this entry I have 466 left to learn. This week I learned “Earthmover” by Have A Nice Life, a song that I’ve said in public is my favorite of all time. Will that still be the case after I’ve learned to play it? Find out below!

Side A

'“Earthmover”

By Have A Nice Life

Deathconsciousness

Released on January 24th, 2008

Liked on January 5th, 2016

It echoed up to me from somewhere deep and dark.

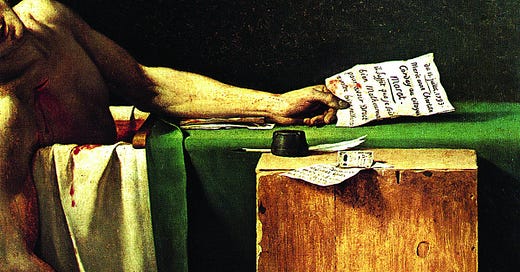

Absentmindedly scrolling through a Pain of Salvation1 fan forum between classes in 2011 my eyes locked onto a familiar name and image. A low resolution version of Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat, half-remembered from a high school history textbook, next to the words “Have A Nice Life - Earthmover”.

A synapse inside my skull summoned up a review I had read in 2008 on the website Sputnik Music. “The most beautiful album of 2008 has already arrived” it declared of Have a Nice Life’s debut album Deathconsciousness. My impression at the time was that the reviewer, an unpaid volunteer, really, really, wanted people to check this album out and was willing to sacrifice clarity in order to achieve that goal. Well, as of 2008 all that effort went to waste. I filed the album away as a curiosity and moved on. Three years later, looking at a different website in a different state and a different state of mind, the seed this overeager reviewer planted finally flowered. I hit play.

Eight years later in 2019 I am backstage at the now defunct Brooklyn Bazaar with my friend and former Kerrang! editor Cat Jones2. We are waiting for Dan Barrett3 and Tim Macuga, the two core members of Have A Nice Life, to finish up their post-show pleasantries and sit down for an interview. The duo and their band are touring to build anticipation for their third record Sea of Worry. Barrett and Macuga have no way of knowing this, but as I sit and sweat out my pre-interviews jitters I am only 24 hours removed from releasing an album of my own, an album whose closing track would likely not have existed if not for the final song of Have a Nice Life’s set. The same song that closes Deathconsciousness. “Earthmover”.

(This isn’t really relevant to the story, but after the interview and some post-interview drinks with Cat, I hoofed it to JFK Airport so I could fly at dawn to New Orleans where I’d join Bellows for the homeward leg of their tour with Another Michael. My friend Jonah spent the day driving my sleep deprived delirious husk around the city, making pit stops to eat the best Vietnamese sandwich I’ve ever had and wander through the Super Sunday parade. Great weekend.)

Liking “Earthmover” on Spotify three years earlier in 2016 was a formality. I was putting together a playlist of songs that inspired the music I was writing for Sisyphean, in case any bandmates or audio engineers wanted a point of reference. “Earthmover” was an early inclusion4. I spent a lot of time listening to this playlist, mostly on long bus rides from my job to my practice space at dusk in the middle of a typically frigid Chicago winter. Each time “Earthmover” rotated back to the top of the queue I became more convinced of a notion that first took hold in 2011, that this wasn’t just the most beautiful song of 2008 but the most beautiful song, full stop.

I’m not going to try and tell you what “Earthmover” sounds like or why I find it beautiful, at least not yet. I want to start by telling you where “Earthmover” comes from.

Deathconsciousness was recorded over five years on a budget of roughly $1,000 in Tim Macuga’s bedroom. Macuga and Dan Barrett, the former singer of the long forgotten Connecticut emo band In Pieces, wrote songs together off and on as a lark, a low pressure way of experimenting with no intention of making it big. Things changed following the death of Barrett’s father. While soul-searching on a travel through Europe (“the stereotypical white guy thing” Barrett told Vice) Barrett invented a backstory for the songs he and Macuga were writing back home, one that involved a fictional medieval cult who worshipped a deicidal archer. Wrapped in this ominous context (laid out in a 70 page booklet that accompanied each physical copy of Deathconsciousness) Barrett and Macuga’s grim songs about dystopian science fiction and suicidal ideation took on a mythic scope. With no backing from a label, Have A Nice Life spread by digital word of mouth, passed around in the recesses of internet forums5 like a ghost story. Year by year the album attracted more converts, drawn in by the album’s humble origins, its haunting aura, and the all consuming darkness of its sound.

As much as I’d like to believe that “Earthmover” can stand on its own merits without all of this biographical context, I love it too much to risk dampening its impact by omitting the juicy details. More over, knowing where “Earthmover” comes from helps explain why it, uh, sounds like that. I’ll be blunt. By any professional standard “Earthmover” sounds like shit. The guitar is almost certainly out of tune. The vocals aren’t always in time with each other. The drums barely hide their origin as a Garageband preset, but they are so loud that they hide pretty much everything else in the song. Except for the bass of course, which plays almost as much feedback as it does distinct notes. Every single one of these flaws is crucial to “Earthmover”’s beauty. In fact, I’ll go one step further and say that Deathconsciousness wouldn’t have half as much acclaim if it sounded “better”. Now, I could trot out all the usual arguments about how the low fidelity recording and less than perfect performances make Have A Nice Life a “realer” and more “authentic” band. Maybe we could even start throwing the words “Punk” and “DIY” around. But while I don’t doubt these old standbys of rock psychology had a hand in building Have A Nice Life’s legend (and acknowledging how personally encouraging it was to hear them make such great work with such simple tools) I’d like to take a different angle. Have A Nice Life’s technical flaws aren’t good for moral reasons, they’re good because they make “Earthmover” a genuine piece of horror fiction.

Scrolling back through the user reviews of Deathconsciousness from 2008 on Rate Your Music, one of the sites responsible for Have A Nice Life’s viral popularity, I kept noticing that no one could agree on the album’s genre. Comparisons vary wildly. Is it shoegaze? Drone metal? Post-punk? Industrial?6 Part of the confusion comes from the sprawling surplus of material on the album, but I’d wager that the opaque production quality helps too. Unable to hear exactly what’s going on behind the dense fog of noise, listeners fill in the gaps themselves. This same ambiguity makes “Earthmover” fertile ground for Lovecraftian horror.

H.P. Lovecraft, if you’re not familiar, was a horror author in the early 20th century from the same general New England neck of the woods as Have A Nice Life. Lovecraft’s great contribution to the genre was a sense of cosmic scale. His protagonists stumble across creatures, civilizations, and gods so much older and vaster than human history that they drive witnesses insane from sight alone. Humans in Lovecraft stories are so roundly insignificant that their minds cannot comprehend the true shape of the universe’s lords and masters. They grasp at indescribable terror for as long as they can until their minds give way entirely.

“Earthmover” earns its Lovecraftian bona fides from two directions. The messy production takes care of the “indescribable/incomprehensible” part, while also highlighting the most eerie parts of the song’s arrangement. No matter how much noise is slathered on, those piano notes still ring out like chimes from deep within the earth’s core. Barrett’s lyrics seal the deal. “Earthmover” describes the end of the world, brought about by enormous immortal golems who reduce the entire planet to “dust and sand”. Barrett keeps the origins of the Earthmovers vague, but gives just enough info to suggest that they were made rather than born (“carved out of stone/earth, blood and bone”) and that whoever let them loose on the world had no idea what they were getting themselves into (“more than a symbol/more than I bargained for”). Any Lovecraft protagonist unlucky enough to accidentally awaken Cthulhu from his sunken city R’lyeh will certainly relate.

When I listen to “Earthmover” (now, in 2011/2016/2019, whenever) I picture impossibly tall humanoid creatures made of rock, older than any known human culture, marching in time to Have A Nice Life’s thunderously slow drums, leaving no survivors in their wake. It is an image almost certainly imported from the opening credits of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä and the Valley of the Wind, which takes place in a world reeling from the rampages of war machines. Barrett’s Earthmovers show no such mercy as to let humanity recover.

One of the common tropes in Lovecraftian horror is the characters finding records from the past that point them to the existence of even older terrors. Old journals, damaged film footage, that kind of thing. This trope experienced something of a moment in the late 00s. Following in the footsteps of The Blair Witch Project, horror directors took the concept of “found footage” and applied it to both domestic anxieties and city-sized devastation. Found footage horror uses consumer-grade technology to undercut the audience’s suspension of disbelief, appearing just enough like reality to force the viewer to consider its whether its events really happened.

Have A Nice Life achieve a similar blurring of reality and fiction on “Earthmover”. By building the recording out of sounds that anyone with a Mac and a few cheap guitars could make it feels less like a song and more like prophecy. This is how the world ends, not with a whimper but with the Brooklyn Kit cranked to 10. Barrett and Macuga don’t settle there, though. “Earthmover”’s real horror comes at its quietest moment. For the song’s bridge, the duo strip away everything but one guitar and Barrett’s voice. By now the golems have successfully cleared the earth of all other life. But don’t expect any celebration from them. Instead, Barrett reveals the final twist of the knife. The same death-consciousness that plunged him into despair on the rest of the record, the same self-destructive suicidal impulse that would lead a cult to kill God himself, lives inside of the Earthmovers too. With nothing left to destroy all they can say for themselves is “we wish we were dead”. No life, no matter how powerful, can escape death.

“Well Christ, Ian,” you might catch yourself saying. “That all sounds pretty depressing. Why on earth would you find that beautiful?”

A fair question, and one that I hope to answer on Side B where we’ll discuss what happened when I learned “Earthmover” on drums.

Side B

“Earthmover”

Drums programmed by Tim Macuga & Dan Barrett

60 BPM

“Earthmover” is a long song. At eleven and a half minutes it is the longest song that I’ve had to learn for Drumming Upstream so far. There are even longer songs on the way, the longest of which will top out at nearly 19 minutes, but off the top of my head none of the other big boys on my Liked list are long in the exact way that “Earthmover” is long. Let me show you a breakdown of the song’s structure so you’ll see what I mean:

Intro - Four measures, 16 seconds long

Verse 1 - 16 measures, 1 minute and four seconds long

Chorus 1 - 8 measures, 32 seconds long

Verse 2 - 16 measures, 1 minute and four seconds long

Chorus 2 - 8 measures, 32 seconds long

Post-chorus - Four measures, 16 seconds long

Bridge - 26 measures, 1 minute and 44 seconds long.

Coda - 88 measure, 5 minutes and 52 seconds long.

There are two obvious answers to the question of why “Earthmover” is so long. First, the song is slow. The first half of the song moves by at one click of the metronome per second. By the time that most pop songs have wrapped up, “Earthmover” has just gotten to its bridge. This slow tempo does a lot for the song. Slowness implies size, appropriate for the apocalyptic scale of its subject matter and for the wallowing it inspires in its listeners. The second reason for “Earthmover”’s length should jump out immediately. The song’s coda by itself is longer than the rest of the song. Once Barrett finishes singing “we wish we were dead” at the end of the bridge he never pipes up again, leaving the final six minutes wordless. The instruments that come in the coda don’t so much fill the void left by Barrett as toss you, the listener, straight into it. All of the distorted bass, guitars, and drums swoop back in with a vengeance. With renewed fury, the band double the tempo and dispense with any illusion of dynamic range. For nearly six minutes straight, Have A Nice Life’s inhuman programmed drums hammer away at a caveman-simple quarter note pulse, never faltering in time or volume. This machine drummer even outlasts the endurance of its human programmers. Near the half way point of the coda Tim Macuga loudly throws the bass onto the floor out of frustration, leaving it to feedback until the track ends. “I physically acted out and ended up in the recording.” Macuga told Vice in 2014 “It was a bit too much to take to keep going with it at a certain point.”

A bit too much is right.

Playing the back half of “Earthmover” is exhausting. Playing the back half of “Eaarthmover” after several takes and false starts in the middle of a New York heatwave might be medically inadvisable. And yet, that’s just what I did. I hope this explains the look on my face and the state of my hair in the video below.

I’ve had a lot of time both on and off the kit to think about the final six minutes of “Earthmover”. Some of these thoughts were pure lizard brain shit. “Ow, my arms are sore”, that kind of thing. As I pushed through the pain, memories flooded in. Memories from places deep and dark. I recalled watching the snow fall, twinkling under the yellow of Chicago street lights in time to the soft guitars on the edges of “Earthmover”’s climax. I recalled coming home from a party in the dark to sleep on a friend’s couch that I called my bed for a few months, staring at the ceiling while the alcohol in my bloodstream turned the rest of the room into a tilt-a-whirl. I remember feeling like nothing mattered at all. It is 2018 and I’m lying on the floor of my apartment after my roommates have gone to sleep, “Earthmover” is blasting on my headphones and I am fighting back tears that aren’t coming from anywhere I can recognize. It is 2022 and I am deeply, mortally, terrified that I will never do this song justice, never be able to explain how and why this song means so much to me.

Then other memories join in. It is 2017. I’ve just moved back to New York and I’m at Have A Nice Life’s first show at Brooklyn Bazaar. It is sold out. I’m 90% sure that one of the hosts of Chapo Trap House is across the bar from me, which is the kind of thing I found very exciting in 2017. It is 2017 and I’m at Brooklyn Bazaar and I am surrounded by people who, like me, felt so strongly about an album made for the price of one month of rent in a New York apartment that we’ve all crowded in against each for space at the lip of the stage. Have A Nice Life are playing “Earthmover” and we are dancing, we are pushing each other, we are crying, we are alive. How is it that so many of us recognized ourselves in an album about wanting to die and found ourselves here covered in each other’s sweat? How did we survive?

It is 2022 and I am beating the living hell out of my drums when I realize that 60 beats per minute at double time is 120 beats per minute, and that 120 beats per minute is practically dance music. 11 years too late that I realize that the ending of “Earthmover” isn’t an act of destruction. It isn’t the soundtrack to golems crushing out all life on earth. It is a rave. It is the release, the affirmation of life at the tail end of death. Being “a bit too much” is the point. Abandoning words for pure sound is the point. The climax of “Earthmover” is the rage against the suffocating, swirling darkness. It is a sign that out there someone real, someone fallible and flawed just like me, feels how I do. Felt how I did and won. Survived. Endured.

So I kept pushing through the soreness and fatigue. I let myself look like a mess. Because if I can endure then so can you. Because I love being alive, and I hope you do too.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

For a second there I really thought I could do it. I thought after digging into the nitty-gritty of “Earthmover” that I’d grow numb to it. Nope. Remember when I said “Carry” would sit at the top of the leaderboard for a long time? I lied.

“Earthmover” by Have A Nice Life

That’s it for Drumming Upstream for now. For the month of August this newsletter is going full travelogue while me and the boys in Bellows work our way across the continent. When I return I have a handful of songs that will require a vastly different set of skills to learn and perform correctly. Thank you for reading. Seriously, I’m glad you are out there. See you next week.

Pain of Salvation will show up a few times in this series, thank god this project isn’t called “Singing Upstream”.

Cat is the host of the podcast Hot Blooded, where she interviews musicians about love. The whole pod is worth checking out, but her interview with Nate Garrett of Spirit Adrift is particularly riveting.

A few more songs from this playlist will show up in this series. A few others already have. I’ll leave it to the more intrepid Lamniformes fans suss out which are which.

If you’d like to read more about Have A Nice Life’s online fandom, I think I did a pretty good job describing it for Kerrang! in 2019

We’ll have more opportunities to litigate exactly which genre Have A Nice Life belong to the next time they show up in this series.