"Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2" by Maurice Ravel and the State of Classical Music in the Age of Streaming

Drumming Upstream #4

Welcome back to Drumming Upstream. In case you’re just joining me, I am learning how to play every song I’ve Liked on Spotify on the drums. When there are no songs left to learn, I will delete my Spotify account. I started with a list of 484. I’ve learned three songs so far. Two other songs were removed by their creators. One was a Joni Mitchell song removed in Spotify’s Rogan-related drama. The other was by the defunct brewer metal band Kylesa, who have given no reason for the song’s disappearance. This brings us to a total of 479.

I began planning this series last summer, long after Spotify earned the organized ire of musicians. I started publishing the series in late January, just before Neil Young became the most prominent hater of the platform. Young removed his catalog from Spotify after issuing an “it’s me or him” ultimatum about Joe Rogan, whose podcast Spotify acquired for $100 million back in 2020. Young’s ultimatum came in the wake of an open letter signed by “a coalition of scientists, medical professionals, professors, and science communicators” concerned over Rogan’s anything-goes attitude regarding facts about the COVID vaccine. After Young jumped ship other musicians followed, citing the same reason, including Young’s generational and musical compatriots Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills and Nash. R&B singer-songwriter India.Arie then announced her own departure from Spotify, posting a montage of Rogan using the N-word on his podcast over the years in her announcement on social media. In short, Spotify has found itself as the latest battlefield for a number of contested subjects in the culture war.

I bring all of this up because understanding how and why a music streaming service paid nine figures to host a MMA announcer’s podcast in the first place is crucial to understanding how this week’s entry fits into the streaming ecosystem.

Side A

“Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2”

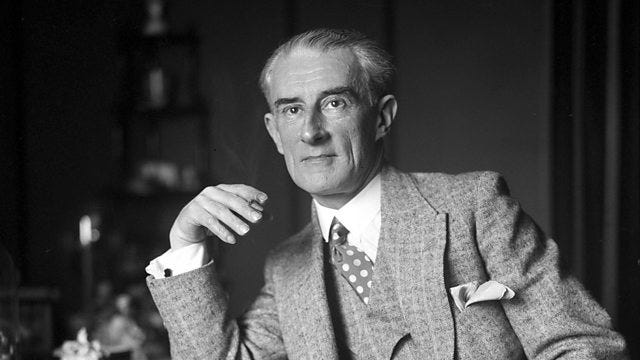

By Maurice Ravel

Daphnis et Chloé

Originally Premiered on June 8th, 1912

Liked on September 16th, 2015

I have never had trouble finding music to listen to. I read a lot of music criticism. I go to a lot of shows, often early enough to catch the openers. My friends send me stuff. For years I’ve kept a running list of albums that I haven’t heard yet, and the music that I have heard is even more rigorously cataloged. If I am in the mood to listen to music it isn’t hard for me to find something. I know where to look and I know what I want. Still, there are rare occasions when I can’t make up my mind. On one of those rare occasions in September 2015 I clicked on Spotify’s “Classical Radio” link and let the algorithm pick for me. I don’t remember much of what Spotify served up. Maybe Mozart or Haydn. A Philip Glass piece for piano certainly, although I don’t remember which one. I want to say that it played part of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, but that’s such a perfectly cliche that I’m worried I’ve fabricated the memory in order to prove my point about how boring the app’s choices were. After frustratedly hitting the skip button one too many times I landed on a recording of Maurice Ravel’s “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” a piece that I was refreshingly unfamiliar with. Either out of pure enjoyment or a desperate need to teach Spotify’s recommendation engine something about who I am, I dutifully hit the Like button.

Maurice Ravel was a French composer active in the early decades of the 20th century. Being French and published in the early 20th century, Ravel’s music gets lumped into the fittingly nebulous style of impressionism, though Ravel was far more precise in his writing than that loose label would imply. Ravel came from a family of engineers and treated his music with the same technical meticulousness that a designer would. But despite their mechanical intricacies, Ravel’s compositions sound hazy and dreamlike. Listening to Ravel is like watching a cloud of mist hover across the surface of a lake, only to discover an artfully arranged fleet of smoke machines on the opposite shore. Take the opening of “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2”. The sound is soft, fluttering, and delicate. In truth, the music is devilishly difficult to perform. To create the illusion of a peaceful sunrise over a serene pasture, the musicians must rip through a continuous stream of notes at high speeds for minutes on end at a low volume. That’s really hard!

“Daphnis et Chloé” is filled with these hidden complexities. A distracted listener might hear it as a collection of pretty but purposeless melodies, but as the score to a ballet the music is dense with leitmotifs tied to specific characters that weave in and out of each other in order to move the story along. It might be hard for modern ears to hear how daring a composition like “Daphnis et Chloé” would have seemed at the time. Many of the particulars of its composition, Ravel’s love of parallel harmony, extended chords, and strange symmetrical scales, have since spread into the lexicon of jazz and film scores.1 I imagine this is part of the reason that “Daphnis et Chloé” stuck out to me when I listened to Spotify’s classical radio. It speaks the same language, roughly, as music that I already enjoy. But that language was brand new in the 1920s. “Daphnis et Chloé” may not have inspired riots the way that Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” did, but the two pieces are chronologically, and spiritually, contemporaries.

When Spotify served up “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” it didn’t give me any of this historical context. Even more than the rest of the music in its library, classical music is deeply mystified on Spotify. Part of the reason I even went with the radio back in 2015 is that finding the right classical music to listen to on Spotify is a pain in the ass. If I pull up the Maurice Ravel “artist page” on Spotify I find a staggering number of recordings from different orchestras, ensembles, and soloists. Searching for “Daphnis et Chloé” isn’t helpful either, as the piece shows up on at least 100 different albums in the Spotify catalog. How does someone with a curiosity for the genre even know where to start with all of these options?

To be fair to Ek and co. this is an ongoing issue with the classical music industry writ large. The genre is taught as a succession of long dead composers who, in their great genius, are solely responsible for the enduring power of their music. But in order to experience the music as anything other than marks on paper, you either need to listen to a recording or attend a performance by living musicians. Despite all drawing from the same score, each of these performers add their own flavor and interpretation to the music being performed. For example, the recording of “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” that Spotify played me in 2015 was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra as conducted by Daniel Barenboim in 1991. This version of the piece does not include the choir section that Ravel originally wrote for the ballet. Even with less pronounced deviations from the source material, different conductors will make minor adjustments in tempo or in how they balance different sections of the orchestra. The same conductor might not even conduct the same piece the same way on two different recordings. A Beethoven symphony recorded in the 2010s is likely to be a whole lot faster than a Beethoven symphony recorded in the 1980s even if both recordings feature the same conductor. To be an active classical music fan requires a oenophile’s attention to detail. It isn’t enough to know the difference between a cab and a malbec, you’ll also need to consider the region and vintage. Needless to say, this is a lot to throw in front of a first time listener who just wants to know whether “Ode To Joy” lives up to the hype.

In the years since I Liked Barenboim & CSO’s version of “Daphnis et Chloé” I’ve learned just enough about who’s performances I like to navigate Spotify’s classical music selection. But Spotify themselves haven’t made it any easier. To illustrate just how little Spotify care about educating their users about classical music, let’s try and recreate the path that led me to Liking “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2.”

Spotify discontinued their Radio feature in 2019, so we’ll have to start by pulling up their classical tab under the explore page. Here’s what that looks like:

Our options are either curated playlists or a strange group of nouns and verbs named Categories. Featured Playlists is at the top of the page so let’s start there. We can already see five playlists, and these give us a useful impression of what’s to come. ‘Classical Essentials’ and ‘Classical New Releases’ are geared at first timers and returning customers respectively, and are both probably closest in spirit and content to the radio that I used in 2015. Then we have two playlists that are less about classical music itself and more about cultivating a mood or an aesthetic2. Finally we have a playlist that, and I’m sorry if this makes me sound like a snob, has nothing to do with classical music at all. ‘Pop Goes Classical’ is a playlist of pop songs arranged for solo piano or strings. No offense if you enjoy this stuff, but pop music played on piano or arranged for strings is still pop music. Let’s take a deeper look into the playlists and see if this general distribution holds up.

I count three more playlists that are specifically about classical music; ‘Classical Piano’ though it puts a premium on being “relaxing”, ‘Classical X’ where all New Music gets lumped together, and ‘The Classical Takeover’ which is again geared at the real heads who follow the genre regularly. Then we have two seemingly indistinguishable mood-oriented piano playlists, a string playlist that promises to “help you relax,” and two playlists that mention classical music explicitly but highlight feel good and romantic (but not Romantic) qualities. Dark Academia gets its Light counterpart, as well as a hornier, older sibling in ‘royalcore.’ Then things get really dire. ‘Not Quite Classical’ and ‘Soundtracked’ again are explicitly billed as something other than what we’re looking for, and ‘Creative Writing’ makes it clear that orchestral music only makes up a small portion of its contents.

So that’s five playlists that are about the music, six mood based playlists, three playlists for vibe curation, three playlists that aren’t the genre at all, and one playlist of background music for an activity. Now let’s take a look at Categories.

More relaxation. More moods. More soundtracks masquerading as classical music. More background music. Only three categories that give us any information about who makes this music, what it’s played on, or allude to any of its actual genre classifications. By now I’m desperate for some Dmitri Shostakovich so I’m going to jump straight to ‘Neoclassical’.

Oh come on.

What have we learned from this quick tour down Spotify’s Classical music aisle? That if we want to learn about the music we’ll have to do that on our own time. If we don’t particularly care about what’s playing, then we can kick back and relax. Spotify does not think of music as music. Music only matters if it is functional. All the complexities of who made the music and how are sanded off so as to not disrupt the mood. Spotify is only concerned with music as audio. Wallpaper at worst and a college dorm poster for overeager freshmen at best. This attitude is the same one that motivated Spotify to gobble up podcast networks and numbskulls like Rogan. It doesn’t matter what nonsense he blathers about as long as people are listening to him blather for a long time. The ideal Spotify account never stops playing audio and the ideal Spotify user never really notices what’s playing.

Look. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with playing music in the background while paying attention to something else. Hell, I have another tab playing Ravel’s piano music as I write this letter. But let’s not pretend that we aren’t selling the music short by acting like it only belongs to the background. Classical music deserves a better fate than this. Ravel, no doubt proud of the precise intricacies of his compositions, balked at the idea that his music was only an impression of something else. No doubt the literal hundreds of musicians that have kept his music alive in the last century would feel the same way about their work being reduced to audio paste. But don’t take my word for it, here’s Daniel Barenboim, whose interpretation of “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” brought us here in the first place:

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

Having spent 2,000 words defending classical music’s honor against the streaming economy, I’m going to relish the chance to knock it down a peg by pitting it against sloppy pop punk sing-alongs and sex-murder rap music. “Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” beats out Joyce Manor on the quality of its execution alone, and its use of text painting is even more comprehensive and imaginative than clipping.’s on “Body & Blood”. But does Ravel have what it takes to topple Springsteen? Ravel squeezes a lot more out of his melodies than Springsteen does, and the huge swells that the Chicago Symphony Orchestra reaches for at the piece’s climax are as heart-achingly beautiful as any Clemons saxophone solo. But if I’m being really nit-picky, I have to admit that I think the fake out ending is a little tacky. “Bobby Jean” is great the whole way through. I certainly didn’t see this coming, but Springsteen reigns for the entire first month of Drumming Upstream.

“Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2” by Maurice Ravel

As I mentioned in last week’s entry, I have to devote my drum practice this month to a paid gig, so next week I’ll pull another drum-less track from the Liked list, this time from the other cornerstone of Spotify’s relaxation station: Ambient music.

If you know where to look you can also hear a lot of impressionist techniques in contemporary rock music. When I first met Siddhu Anadalingham of Semaphore, he pointed out that shoegaze and post hardcore use of a lot of the same harmonic language as Debussy and Ravel.

I know that I spent a long time in last week’s newsletter talking about Tumblr, so this might come as a surprise, but I cannot explain what Dark Academia is. From the bits and pieces I’ve picked up second hand I think it’s a cosplay-adjacent fashion style meant to invoke a fantasy author’s idea of attending an old British college. Seems like a way of doing Harry Potter without doing Harry Potter. But what do I know!