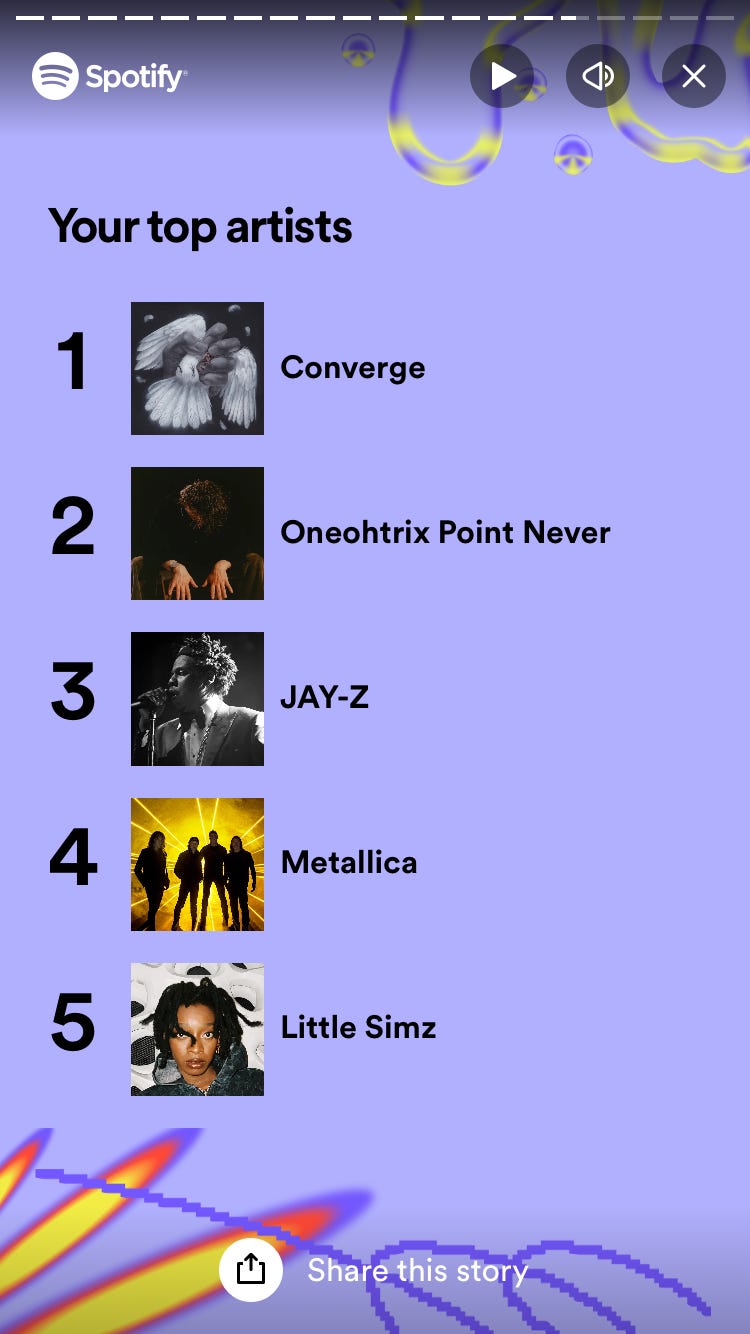

Spotify is Wrapped again, and this year it’s telling everyone to move to Burlington. The audio streaming company, as they have for years, presented its users with a colorful regurgitation of the data they’ve quietly collected while you and I listened to our favorite records. This year in addition to telling people what music they spent the most time listening to with charts shaped like hamburgers, Spotify gave relocation suggestions to users based on which city’s data lined up best with their own. The app concluded that a preposterous number of my friends, straight and gay alike fwiw, should all hitch it to Burlington, Vermont. Though likely intended as a neat bit of trivia triggered by Big Thief passing some mysterious play count threshold, the Sound Town feature couldn’t help feeling like an inscrutable insult aimed at indie rock fans of a certain age. But Spotify didn’t just have jokes for Carhartt enthusiasts. Spotify told me to move to Portland, Oregon, citing my high play count for the metallic hardcore band Converge as damning evidence. Ouch. I have been owned, but no more owned than I’ve been by meme pages ran by aging marketing guys and alt girls on Instagram.

For all of the data they had on me, I still know something that Spotify does not. I know why I listened to so much Converge, and if you’ve been reading this newsletter this year you probably do too.

Four of the top five acts on my Spotify Wrapped, Converge, Oneohtrix Point Never, Jay-Z, and Little Simz, were artists that I covered for Drumming Upstream this year. They all also happen to have deep catalogs that make my research phase richer with play counts than the average artist. Sure, I happen to like them all quite a bit, but there were external factors completely unmeasurable by Spotify for their high marks at the end of the year. The only exception were Metallica, and here again Spotify can’t give us a full picture. First of all, if you think Metallica aren’t going to appear eventually in Drumming Upstream then buddy, you don’t know me from Adam. I knew Metallica would end the year on this list the minute they released their latest album 72 Seasons earlier this year, and I imagine any of my friends who sat through unprompted and impassioned defenses of the album since its release could have guessed Metallica would crack the top 5 too. Metallica are a safe bet to medal in any of my yearly Wrapped rankings, but their presence this year has an interesting wrinkle. I didn’t just listen to a lot of Metallica, I listened to a lot of late period Metallica. I’m talking Death Magnetic, Hardwired and the latest. I spent more time with those three records than the legendary first four albums from Metallica’s 1980s peak. Fixating on objectively less good Metallica and still having a great time is by far the most 30-something music nerd thing I did all year.

So yet again my conclusion about Spotify Wrapped is that it can’t tell me anything I don’t already know. And yet again Spotify need as much of the free advertising that they can coerce out of their users, because the rest of the news has not looked quite as nice. Spotify, in an act of Buddha-like acknowledgement of the karmic balance of the universe, also made headlines recently first for announcing that they played to demonetize any song that earned less than 1,000 plays a year, and then for laying off roughly 1,500 of their employees. After careful consideration I was ready to mount a controversial yet well reasoned defense of the new monetization policy until the news of the layoffs made the idea of defending Spotify far less appealing. These Swedes just can’t get out of their own way!

Of course both of these changes are part of the same strategy. Now that Spotify is actually profitable, it is time for them to cut costs and get serious. The hiring glut that they took on during the pandemic in constant pursuit of scale above all was inevitably going to turn back the other way and vomit tech workers back onto the streets. For all the smack that I talk on the company, I feel for anyone that got the boot from Ek and co. I hope they can get hired somewhere else soon and that the rest of their former coworkers consider organizing in case more cuts are coming down the pipe.

Before I comment on the new payout policy however, I want to make my own position as clear as possible. Below you can find the stats that Spotify provided me as an artist:

I’m sharing this to make it as clear as possible that I in no way stand to benefit from the new system. The vast majority of my music does not cross the 1,000 play threshold. None of the six songs on Sisyphean or the eight songs on You Can’t Do This Alone qualify. The logic behind Spotify’s decision to demonetize songs like these is that the rest of the Spotify catalog that does get played more than 1,000 times a year will earn more money for their rights holders than before. In the best case scenario this means that I am out roughly $41.961, which will instead be divided amongst more popular artists.

Why, if I am out potentially $42 bucks a year as a result of this change, do I support it? First, because almost everyone other musician that you or I have ever heard of stands to benefit instead. I’m not joking, way way way more artists than you’d expect *crush* the 1,000 play mark yearly. Do you remember “Antares” by Stella Luna, the song I spent 3,111 words calling obscure and mysterious earlier this year? It’s got 49,065 total plays on Spotify. I’ve been revisiting a number of my favorite records of the year, many of them made by metal bands that even the average long-hair in a leather jacket would draw a blank on, and only one of them has failed to reach the 1k mark for their whole album. Flat out, if you are in a band with even a modest following, this new policy will help your margins, not hurt it.

But what about schlubs like me that don’t measure up? Look, I’d prefer to have the extra $40 at the end of the day but let’s keep things in perspective. I make more money than that from three shirt sales a year on Bandcamp, or from a single discounted yearly subscription on this newsletter. No one is losing an honest living from this reallocation. Instead, what Spotify has given them is a clarification of terms. Are you willing to pay up to $3 a year per song for the chance of one day earning more than $3 per song a year? If that math doesn’t add up for you then its in your best interest, and Spotify’s what with the storage costs for their massive library, to take your business elsewhere.

Lest you mistake me for some “coffee is for closers” music biz tough guy, I think it would be rad as hell if underground artists left Spotify in droves. Spotify in its rapid expansion has attempted to be the audio platform for every type of artist and every type of fan. But it wasn’t that long ago that bands with strong DIY followings across the country only put their albums on Spotify after years of selling them on Bandcamp. Before it was a safe assumption that every album was readily available to stream, audiences were happy to buy music directly from their favorite underground bands. Even with a smaller overall reach, indie artists made off far better in this arrangement. Artists that weren’t rolling in Bandcamp sales still had something crucially missing from our current set up. As one bandmate of mine put it, “being unsuccessful gives you dignity of not giving a shit” about things like Spotify. With this final insult of denying even the humblest artist their due cut Spotify has given the underground a chance to regain that dignity. If you ever wanted to build a robust music scene outside the dominant modes of distribution, there’s no better moment to back that sentiment up with action.

Don’t get me wrong, no matter how much Spotify’s new system stands to improve its payouts to even marginally popular artists, the business model still doesn’t make a lick of sense for artists unless they a) own all of their masters and publishing rights or b) have enough fans to make up for the costs those other parties are going to drain before you get your cut. In short: unless you’re Taylor Swift you’re getting a raw deal. Spotify can and should pay artists more and I support any attempts to pressure the company to do so. But there are bills and rent due in the present, and I have no interest in waiting around for Daniel Ek’s green heart to grow three sizes.

Here, without any further ado, is what I’ve done in the meantime instead:

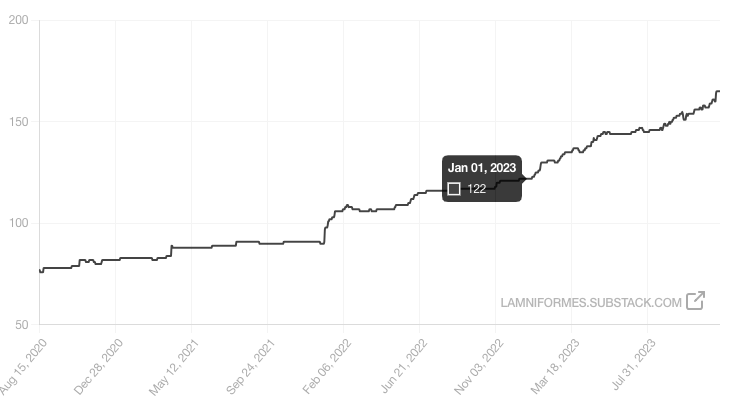

This has been a good year for Lamniformes Cuneiform. I ended the year with more subscribers both free and paid than I started and I’ve consistently gotten more views a day than I did a year ago. You’ll notice that the rate of growth in the chart above has also picked up since the start of the year and especially in the second half of 2023. I attribute that trend and the comparable trend of overall views rising around the same time to getting consistent with Five & Five on Friday. Posting regularly helps get people in the room. Writing well is what keeps them there. I knew that I was writing well, but I needed to find a way to publish consistently instead of relying on the off chance of a piece going viral to bring in new readers. Five & Five has absolutely been a success in that regard. It has made the newsletter easier to write and easier to read.

After a year of tinkering I’ve decided to make a few changes to Five & Five that will make it even more appealing to potential subscribers. Here’s how it’s going to work. Going forward Five & Five on Friday will now be Fives on Friday. That’s right, I’m adding more fives! In addition to five recommendations and five micro reviews a week, each Fives on Friday will include five track reviews from my Listening Diary and five discreetly labelled pieces of self promotion. These changes mean that I’ll be able to share more music with my readers, and that my recommendations won’t be clogged up with news about my upcoming shows, podcasts, and Lamniformes releases. As a consequence of this reshuffling I’m retiring the Listening Diary as a distinct series. That feature never made much sense behind the paywall. I’d prefer that all of my subscribers get a chance to check out some rad tunes every week and I want to give my paying subscribers something more substantial than five blurbs every other week.

What’s going behind the paywall instead? Drumming Upstream.

Let me not mince words. Drumming Upstream takes a lot of work and time to put together. It takes time to learn songs on drums, time to record and film my covers, time to research, and time to write. Not to mention all the time spent organizing my project files and maintaining my meticulously detailed spreadsheets. The results of this work are self-evident. The first 39 free entries of Drumming Upstream have proved that the series has legs. Not to toot too loudly on my own horn but I think I’ve done great work over these two seasons, and from what I can tell people seem to enjoy reading it. Still, I’m under no illusion about Drumming Upstream being anything other than a niche product. A book-length specialty music magazine about a single person’s favorite songs in their mid-to-late 20s from the perspective a single musical instrument is not going to be for everyone. If it has been for you, I hope you’ll agree with me that it is worth paying for. And if it’s not worth it for you, I hope you’ll find the new and improved Five & Five to be an adequate replacement.

One cost of getting Fives up and running is that my pace for Drumming Upstream slowed this year. I published fewer overall entries this year, but my average word count was higher. Also, despite writing about fewer songs I didn’t drum any less in 2023. To explain what I mean, join me for the second annual…

~~~~~ Drumming Upstream: WRAPPED ~~~~~

Best Written Entry: “Theme From Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me” by Angelo Badalamenti

In this case, “best written” equals “had the most fun while writing”. I said as much in this piece itself, but I had a blast reading and watching interviews with Angelo Badalamenti, even/especially when he retold the same stories in all of them, the same way hearing the same stories from your friends and family goes from being annoying to comforting over time. This entry also sticks out to me because it led me to learn about drummer Grady Tate. Tate, despite playing with tons of big name artists, had never made it onto my radar before. How could I not be excited to find out about a singing drummer who hates taking solos? And finally, I enjoyed trying my hand at film criticism for this entry. I love writing about movies, but I rarely give myself the time to indulge in the habit.2

Most Difficult Entry (written): “An Encyclopedia” by Milo

This was the only entry for which I experienced full-on writer’s block. The harder I worked to get on “A Encyclopedia”’s wavelength the more self-conscious I was about getting it wrong. Writing about rap isn’t my strong suite, though as you’ll see below I had a lot of practice to fix that this year, and to make matters more complicated Rory Ferreira spends a good chunk of this song interrogating where white rap fans get off telling him anything about his work. I have a lot of respect for how Ferreira conducts his career, and for his music. I had to go over every word of this entry with a fine-toothed comb to square my respect and my self-consciousness. The piece is better for it, but it was not a fun experience.

Best Performed Entry: “Wake The Dead” by Comeback Kid

This song felt like the season’s final exam on the kit. “Wake The Dead” challenged my speed, coordination, and my memorization. As I say in the entry, the drums on this track feel composed and very specific, which combined with the hi-fi recording quality meant that I had zero room to fudge any of the parts. I think I rose to the occasion, applying the speed and chops I’d developed learning Converge with the coordination I’d honed on Chvrches. Of all the songs I’ve learned this year I think this one would impress a pre-Drumming Upstream Ian the most, and it’s the one that shows the most of what I’m capable of outside of my “day job” in Indie Rocking.

Most Difficult Entry (Drumming): “Playing Dead” by Chvrches

Do not mistake heaviness and intensity for difficulty. Coordination and precision are much harder to cultivate than raw speed. No part of any song this year took me longer to learn than the bridge to this tune. It forced me to get creative with my cymbals to replicate the band’s digital percussion, and it took months of revision to adapt the part for four human limbs. The rest of the song wasn’t too tough, but focusing so intently on the bridge made me a bit stiff even during the easy parts. I could have done a better job syncing up my snare, although I’ll take my imperfections as a sign of my supposedly human touch.

Here are some stats!

Total Number of Songs: 18

Total Number of Distinct Acts: 18

Total Word Count: 55,350

Average Word Count: 3,075

Songs Learned on Drums: 16

Songs with Live Drummers: 9

Songs with Produced3 Drums: 7

Drumless Songs4: 2

Average Song Length: 4:52

Longest song: “Black Man” by Stevie Wonder (8:30)

Shortest song: “Towing Jehovah” by Converge (2:21)

Average BPM: 92 bpm5

Time Signatures Represented (# of Uses):

4/4 (16)

3/4 (2)

5/4 (1), 6/4 (1), 6/8 (1)

Song With The Most Time Changes: “Towing Jehovah” by Converge (4 total time signatures)

Countries Represented (# of Artists):

USA - 136

UK - 4

Canada - 1

Genres Represented (# of Songs):

Years of Release (# of songs):

1976, 1980, 1992, 1998, 2002 (2), 2005, 2012, 2013 (3), 2015 (6), 2016

The first thing that jumps out to me is the commanding lead that rap took over the rest of the genres this year. I decided this year that with so many numbers working against me in Drumming Upstream that I needed to gain an advantage somewhere in the production process. I started prioritizing songs that I could learn quickly. Most rap songs are built on loops which simplifies my job enough to send up the queue while I chip away at more involved tunes. This had the side effect of forcing me to write about rap more, which as I’ve mentioned is a skill that I’ve needed to develop anyway.

No surprise that songs from the 2010s have a strong majority of the rest of the field. I used the Like button in the mid-10s to keep track of new favorites, which meant drawing from a lot of contemporary releases. I have a hunch that the older songs on my Liked list tend to be more difficult on drums than the contemporary stuff, but I don’t have any strong data to back that up. I don’t think it’s unrelated that only three songs from this season cracked the top 10 on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard, though Angelo Badalamenti, Mitski and Little Simz all got close. New favorites don’t always stick around to become old favorites. While I still enjoy a good number of the songs I learned this year, I suspect that this season contributed more to the middle of the Final Leaderboard than the top.

Finally, if last season’s big theme was songs about being subsumed into oblivion (Washed Out, Marissa Nadler, Isis, and Alcest) before concluding with a confrontation with death (Iron Maiden), this season was all about the conflict between intimacy and mystery. I wrote about DJs hiding behind masks and obscure shoegaze groups. I wrote about old pros hiding their personal histories behind universal sentiments, and cagey millennials giving away less than they seem to. I suppose it’s only fitting that I decided to put Drumming Upstream behind the paywall after spending so much time thinking about what artists choose to give away and what they choose to withhold.

Speaking of Season 1, let’s take a look at how the stats look when we bring in last year’s numbers:

Drumming Upstream Wrapped (S1+S2)

Total Number of Songs: 39

Total Number of Distinct Acts: 35

Total Word Count: 118,289

Average Word Count: 3,036

Songs Learned on Drums: 32

Songs with Live Drummers: 18

Songs with Produced Drums: 14

Drumless Songs: 7

Average Song Length: 5:53 (353 seconds)

Longest song: "Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2" by Maurice Ravel (16:32)

Shortest song: “Towing Jehovah” by Converge (2:21)

Average BPM: 94

Time Signatures Represented (# of Uses):

3/4 (2), 4/4 (32), 5/4 (1), 6/4 (1), 6/8 (1)

Song With The Most Time Changes: “Towing Jehovah” by Converge (4 total time signatures)

Countries Represented (# of Artists):

USA (22)

UK (6)

Canada (2), France (2)

Sweden (1), Germany (1), Norway (1)

Genres Represented (# of Songs):

Rap (6), Punk (6)

Ambient (5)

Heavy Metal (4), Pop (4),

Rock (3)

Dance (2)

Classical (1) R&B (1) Soul (1) Jazz (1), Folk (1)

Years of Release (# of songs):

1912, 1976, 1980, 1982, 1984, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2002 (4), 2004, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2011 2012, 2013 (7), 2014 (3), 2015 (9), 2016

It is very eerie that my splits between live drummers and produced are identical year to year. It turns out that the only reason I published fewer entries this year is that I didn’t cover as many drumless tracks. I wonder how long that distribution can sustain itself. There are a few other trends that really pop out when you take the first two years in tandem. The United States and 4/4 take commanding leads as the most popular locations and time signatures. 2015 has more songs covered than the entire 20th century combined. The composite song continues to settle into the length and tempo of an older Lamniformes tune, and while I suspect it’ll continue to shrink in length over time that Ravel tune is going to keep it pretty hefty for a while. After spending most of my life being “the metal guy” in most rooms I enter, I find it funny as hell that rap and ambient are both burying metal in this project. Don’t worry though, the heavy tunes are on their way.

Thanks for reading and watching me drum this year. It has been an honor and a pleasure. Drumming Upstream will return in January for Season 3, beginning as the other two seasons have with a song from our old friend Bruce Springsteen. Until then, have a great December.

14 songs played 999 times, each earning $0.003 per stream

Maybe because if I let myself get started, I won’t rest until I’ve written 6,000 words and somehow roped long dead classical composers into it somehow, but that’s neither here nor there.

Produced in this context means drums that are sampled, programmed or otherwise attributable to a producer rather than a drummer playing on an acoustic kit.

Drumless tracks are excluded from BPM and Time Signature stats, since I log that data while learning the song on drums.

For songs with multiple tempos I take the average of the tempos, and for songs that “wobble” within a limited range of BPMs I take the median, but I also use my contextual information as a drummer to weigh certain BPMs heavier in my calculations.

I counted Mitski as an American artist based on the precedent of counting Scott Walker as British last year. Despite spending her formative years elsewhere, Mitski’s musical career has taken place primarily in the States. Will this precedent one day bite me in the ass? Probably.

For the purposes of this newsletter I am counting Converge and Comeback Kid, both hardcore bands, and Julien Baker, by virtue of her unmistakeable emo-ness, as punk.

I’m counting Oneohtrix Point Never as ambient, but I don’t feel great about it.