Welcome to Season 3 of Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 439 songs to go!

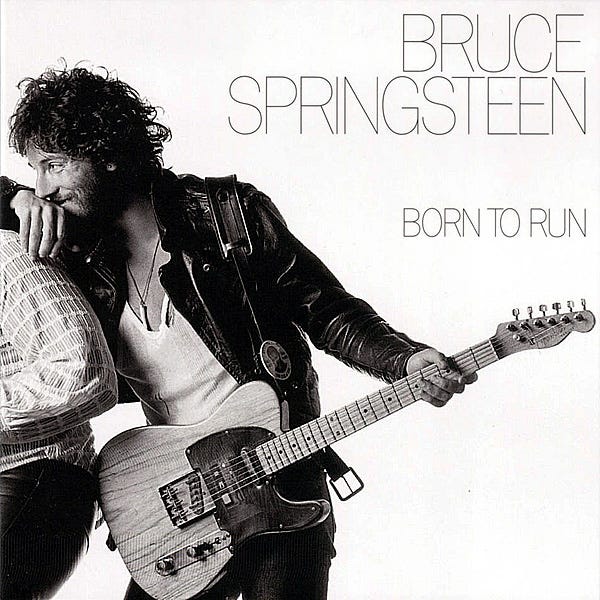

This week I learned “Backstreets” by Bruce Springsteen from his career-making third album, 1975’s Born to Run. Appropriately, this is the third song of Springsteen’s to appear in Drumming Upstream, following “Bobby Jean” (DU#1) and “The River” (DU#24). If you haven’t read those prior entries, I’d recommend catching up before jumping into this one.

Drumming Upstream is a recurring feature exclusive to my paying subscribers. You can access this entry and the full Drumming Upstream archive for $5 a month. Your support and your time are greatly appreciated.

Side A

“Backstreets”

By Bruce Springsteen

Born To Run

Released on August 25th, 1975

Liked on January 23rd, 2016

Astute readers may have noticed that my writing thus far on Bruce Springsteen has lacked a crucial phrase. Only once in the last two entries did I write the words “E Street Band”. To long-time Springsteen fans and rock history sticklers this omission is a grave one. Baring the decade between 1989-1999 that Springsteen spent as a genuine solo artist, the Boss’s employees have been an essential part of his recording and touring career. One need only look at the full gatefold cover for Born to Run or graze the slimmest selection of live footage to see how important the E Street Band is to the Bruce Springsteen experience and its attendant iconography. I can’t claim to have ignored the band out of ignorance since my exposure to Springsteen came long after he reunited with the group in 1999. Nor can I claim to have left them out of the picture deliberately. They’ve simply been crowded out by the sheer magnitude of Springsteen himself. Bruce Springsteen is, without question, among the most famous, commercially successful, and critically lauded artists that I’ve covered in this series. As I described in my first two entries, he is an artist ubiquitous enough to soundtrack the waiting rooms of doctors’ offices, and respected enough to be assigned as high school English homework. Heck, by the end of this entry I’ll have written 8,510 words about him, a significant leg up over any other artist thus far. His celebrity and the force of his on-record and on-stage persona are larger enough than the lives of his bandmates as to render them invisible.

This was not always the case. Rock stardom has a way of seeming inevitable in the rearview mirror. Of course they were going to be huge, how could they not be if they are huge now? And yet, prior to the release of Born To Run, Springsteen’s legendary status would have been inconceivable to anyone but the most evangelical of supporters. His first two albums, Greetings From Asbury Park and The Wild, The Innocent, & The E Street Shuffle both released in 1973, were commercial flops and his live audience was limited to clubs along the Northeastern coastal states. Springsteen did have one advantage however. As small as his audience was, it happened to include a grip of rock critics willing to extol his virtues in the pages of magazines and local newspapers. One critic, Jon Landau, went so far as to declare Springsteen “the future of rock and roll” in The Real Paper before hopping the fence and joining the Born to Run sessions as a producer. Still, effusive praise from journos and a reputation for killing it live do not guarantee a career by themselves. If they did, Krill would be suing Joe Biden for using one of their songs in a campaign ad by now. No, if Springsteen was going to fill the prophetic shoes Landau had picked out for him he’d first have to deliver some real hits. Written and recorded with the desperation of a final shot at glory, Born to Run fit the bill. The album’s eight songs translated the potential energy Springsteen’s critical supporters had promised into enough kinetic force to crack him into the international market. From there he and the E Street Band never stopped running.

The success of Born to Run raises two lines of questioning that orbit each other like a binary star: what did Springsteen’s early audience see in him, and why did it take Born to Run for the rest of the world to catch on? Like most breakthrough albums, Born to Run is a transitional release that contains both the past and the future. “Backstreets”, the fourth and final track on the album’s first side is as close to a median we’re going to find within that transitional moment. I’d argue that it’s an even better example for the purposes of this newsletter than Side B’s opening track, “Born to Run”, despite “Born to Run”’s significantly higher public profile. “Born to Run” is in fact too singularly popular, too emblematic of Springsteen’s music as a whole to be reduced to a portrait of 1975. Besides, I already learned how to play “Born to Run” (yes, even that one fill) for a Sharpless show at Silent Barn in July in either 2011 or 2012. We listened to Gloss Drop by Battles in the car ride to Ridgewood and definitely called it Bushwick at the time, so yeah it was probably 2011. Fun show! We even had a guest saxophonist! But I’ve gotten off track here…

“Backstreets”, a song written for the stage and arranged for the studio, built out of nostalgia for rock’n’roll’s past and fueled by doomed longing for the future, is the center of the venn diagram between Springsteen’s early period and his run of classic records in the late 70s and early 80s. Like the Springsteen to come its aims are universal. Like the Springsteen of old, its concerns are hyper local.

Even without looking for footage of his shows from the early days, it isn’t hard to imagine why Springsteen caught on with Northeast audiences. His first two albums are singing straight to the local choir, breathlessly detailing the characters that populate the boardwalks and scorched city blocks of the tri-state area. Springsteen wrote about these subjects with the enthusiasm of a toddler in the throes of dinosaur-obsession. He simply does not shut up, and neither does his band. Early Springsteen is an avalanche of syllables, alliterative nicknames, drum fills, bass fills, and sax solos. It sounds like a mess on wax, but it isn’t hard to imagine why all of that energy, organized by Springsteen’s stage presence, would whip a hometown crowd into a frenzy. The songs go on forever not just to fit in all of the instrumental digressions and extra verses, but as a way of keeping the party going. The fun doesn’t always translate to the home stereo. I get why longtime fans might have a sentimental attachment to this period, and this very series will eventually attest that there is some primo stuff on The Wild, The Innocent, but I can see why it didn’t break out.

“Backstreets” keeps what worked on those first two albums, the youthful exuberance and widescreen ambition, but streamlines the presentation significantly. The E Street Band, even when pianist Roy Bittan’s and bassist Garry Tallent’s fingers are at their itchiest, always frames Springsteen’s voice instead of just giving him something to shout over. Instead of the jazz fusion jam that would usually erupt in the rhythm section, new drummer Max Weinberg sticks to a tom-heavy heartbeat reminiscent of the “Be My Baby” beat I discussed in DU#39. I’ll have more to say about Weinberg on Side B, but this retro-even-for-1975 drum beat points to part of Springsteen’s appeal with writers. Like a rock critic, young Springsteen was a student of the genre’s history who treated it with religious seriousness. His music self-consciously reached backward to the rock singers and girl groups of the late 50s and early 60s. Born to Run went the extra step of emulating the monophonic recording quality of the era by slathering the instruments in anachronistic slap-back delay, something that would have been impossible on the hectic early records. As Robert Christgau pointed out in his excellent examination of the critical cult of Springsteen in 1976 for the Village Voice, this nostalgic style had a twofold appeal. Younger listeners who weren’t there for the first go around got to hear the old tricks for the first time, and older fans got to relive their own childhood. This feeling has only compounded as more time has passed. Born to Run, by capturing 1975’s idea of 1963, feels like the past twice-refracted into timelessness.

For Springsteen, there is no lyrical theme more timeless than failure. Sung entirely from the first person to a mysterious “Terry”, “Backstreets” tells the story of a relationship doomed by circumstances and by the combustive force of its own passion. Though dotted with beach houses, drag races and other images specific to his New Jersey milieu, Springsteen’s lyrics otherwise focus on the feeling rather than getting bogged down in the details. The Phil Spector-inspired production does him a big favor here. The instruments sound like they’re being played behind heat distortion, shimmering and wavering the way memories of summer nights can blur into one long gradient. Who these doomed youths are and what drove them apart remains a mystery. They could be junkies, street gangsters in matching leather jackets, or just rockers on rough times. What matters is that they cannot escape “the fire [they] were born in” and are cursed, whether together or apart, to haunt society’s outskirts.

“Backstreets” is rock music as an opera about itself: its recognizable rhythms and forms stretched out to house all the pathos the old 45 RPM singles inspired but could never contain. It is rock music as rock critics wished they could make you hear it. Springsteen’s melodrama flatters the sensibilities of anyone who, like me, has ever paused to reflect on the sublime beauty of “Shout” instead of just dancing along. It is both a celebration of rock music’s transcendent power and a tragic acknowledgement of the limits of that transcendence. After the song’s third verse, when the silver-screen worthy dreams its characters envisioned for themselves run against their sad reality, “Backstreets” takes once last victory lap. Over a bridge that never seems to end, Springsteen repeats their fate, “hiding on the backstreets” as The E Street Band builds to a fever pitch behind him. This build up is tailor made for crowd singalongs, a karmic destiny that it has fulfilled in increasingly huge venues over the last 50 years. It goes on forever because it has gone on forever. The backstreets run long enough to contain each successive generation that feels that they too are on the outside, dreaming of something better than what they were born in.

Of course a doctrine this righteous would cause its followers to focus more on the messiah than the apostles, but on Side B I’d like to focus how one member of The E Street Band in particular helped spread the gospel.

Side B

“Backstreets”

Performed by Max Weinberg

94 - 103 BPM

Time Signature: 4/4

Another reason that Born to Run feels like a transitional record is that it is the first of Springsteen’s to feature Max Weinberg on drums. We’ll have a chance to talk about The E Street Band’s previous drummer, Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez, another time. For now, that the listing seeking his replacement asked for “no junior Ginger Bakers” should say enough by implication. Weinberg was brought in to keep things simple and follow along, not to tear the kit to shreds every night. That he was the man for the job should be self-evident from my covers of “Bobby Jean” and “The River”. Weinberg has no problem sticking with a single, simple groove for a whole song. What makes “Backstreets” interesting is how this workman-like approach runs up against the last vestiges of Springsteen’s early style. Unlike those two 80s songs that find their groove and stick to it, “Backstreets” is a moving target, shifting tempos and stretching out the form to accommodate its operatic tone.

I should take a moment to describe exactly what I mean when I talk about “Backstreets”’s form. You’ve undoubtably noticed that the song is six and a half minutes long. That puts it closer to the heavy metal songs I’ve covered in this series than the other Springsteen tunes. But “Backstreets” is not some linear riff fest. Springsteen takes his classic verse-refrain approach to songwriting and augments it with a few self-indulgent flourishes. Springsteen was 24 when he wrote the tune after all, a fact that feels irreconcilable with his reputation as your dad’s favorite dad rocker. We shouldn’t begrudge him for his youthful unearned confidence. Springsteen front-loads the track with a lengthy piano overture by Bittan, outlining the song’s main melodies a solid 10 BPM slower than they’d later be played. Once the band has entered and Springsteen’s worked his way through two verses things start getting fancy. Pushed on by an a crescendo snare roll and an ascending line from Bittan, The E Street Band launches into a new key for the bridge. Here, the partnership at the heart of the song finally ruptures. Springsteen howls, and Weinberg pounds the snare hard enough to steal his son’s old gig1. With the tension at the highest, the band returns to a super-charged arrangement of the verse for a guitar solo before returning to normal in the third verse. But of course, nothing can return to normal. In all three of the songs that I’ve learned Springsteen has saved something special for the third verse. A few extra bars, a new chord progression, or a new twist in the melody. In any other song this third verse extension, when Springsteen unleashes the full burning rage of his baritone, would be the climax. Instead, as we’ve already covered, Springsteen goes for rock glory with an eternal buildup, and the rest of the history.

Needless to say, this is the first of Weinberg’s drum parts where his background in musical theater really shines. Everything about his playing is based on the feeling that Springsteen is trying to convey downstage. Weinberg starts slow and builds the tempo one verse at a time, matching the way Springsteen rises from his lower register into his iconic ham-sandwich bellow over the course of the song. Weinberg only adds fills to match Springsteen’s building excitement and to push him into the track’s next peak. Because “Backstreets” is longer than the other two songs I’ve learned, Weinberg also gets more space to play more than just one drum groove. There’s the tom groove that thumps underneath “Backstreets”’s verses and the full kit backbeat during the chorus, bridge and climax. For the guitar solo version of the verse, Weinberg adds some extra heft by playing the snare on the beat 2 and crashing the hell out of his cymbals. But maybe this would make more sense if you watched me demonstrate.

For this performance I wore my jean jacket because I’ve already used my two flannels on the other Springsteen covers.

The funny thing about playing “Backstreets” multiple times in a row in search of the best possible take is that you really feel the difference in tempo from where the song starts to where it ends. When you’re in the middle of the song each step up the metronome happens gradually, almost imperceptibly, with the exception of the ecstatic rush into the guitar solo. When you loop the track the beginning seems laughably slow compared to the cruising altitude of the finale. If you’re not sure why a change in tempo would be funny to me, let me explain the punchline. I was taught to hue as close as I could to metronome-perfect time, and for years this approach helped me consistently improve on the drums. But as I’ve learned more and more songs, I’ve realized that plenty of them are completely unconcerned with a consistent tempo and are objectively better for it. It rules that the guitar solo is so much faster than the rest of the song, and that the build up pushes the tempo into a completely new range. These changes don’t happen arbitrarily, they’re a crucial part of the song’s identity. I can still see the value of teaching click first, but holy cow does it leave out the full story.

Because these tempo changes felt so natural, I instead focused most of my attention on Weinberg’s fills and his cymbal accents. I’ve noticed that Weinberg is very intentional about his crashes, often saving them for a last second surprise. He’s just as sparing with his fills. Most of them are straight forward single stroke rolls that charge head first into the downbeat. But every once and a while Weinberg will veer off into his own syncopated pattern, as he does at the end of the build up. When I looped that moment just before the climax to learn the fill, my ear started fixating on what was happening on piano instead. In the span of two bars Roy Bittan lays out a clanging, ascending piano fill that Arcade Fire replicated nearly verbatim on “Neighborhood #1 (Tunnels)”. This realization made me recall my Dad walking into the living room while I was listening to Funeral in 2004, nodding approvingly and saying “sounds like Bruce Springsteen”.2 The backstreets stay the same even when the names on the signs change.

There are other feelings of a drastically different temperature that playing “Backstreets” on repeat bubbled up, but those feelings are best discussed below on The Drumming Upstream Leaderboard.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

I’m writing this section on December 28th, 2023. Today is the second anniversary of my friend and Sharpless bandmate Montana’s sudden and unexpected passing. Anyone that knew Montana will tell you that she was a huge fan of Bruce Springsteen. Every time that I’ve listened to “Backstreets” while preparing for this letter I’ve remembered a party at Montana’s first apartment in Chicago in what must have been 2011 or 2012. The apartment’s wifi was named Aubrey Plaza’s Plaza, so I mean… it was probably 2011. Anyway, without fail every time I’ve listened to “Backstreets” an image flashes across my mind. I’ve arrived early at the party. A vinyl copy of Live 1975-85 is open on top of the record player and Bruce is playing over the speakers. I can’t see Montana but I can hear her singing along in another room. I know in this moment that friends are on the way. The night is just getting started and it will only get better from here.

It took three years of starting the year with a cover of a Bruce Springsteen song to realize how much I wish she could read this, how badly I miss being able to ask for her perspective and expertise. This project’s presence in my life has coincided with her absence from it. The deeper in I get and the more that my life changes along the way, the sharper that divide will feel. By learning this song when I did I ran right up against that edge. The second image that crosses my mind when I listen to “Backstreets” is the long walk from my apartment to the stoop where my friends had gathered the night that she died. That walk lasted the exact length of Born to Run. I put on Born to Run because I didn’t know what else to do. I still don’t know what else to do.

“Backstreets” has a heavier burden to bear than any other Springsteen song that will appear in this series. Because I’ve attached it to a hole in my life that cannot and will never be filled, I’ve made the song as much a part of my life as that hole. “Special” falls catastrophically short of describing what having that kind of a relationship with a song is like, but its the only short hand I can at present muster. In either case, having a special relationship with a song is a different thing than loving a song. I like “Backstreets” a whole lot. Few songs can claim to have a peak worthy of goosebumps, and “Backstreets” has at least two of them. But if I’m being honest, personal connection and professional admiration aside, I prefer Springsteen when he’s succinct. Of the three songs of Springsteen’s that I’ve learned so far, this is my least favorite, which puts “Backstreets” just outside of then top 10 at 13th. Springsteen will still have a handful of cracks at the leaderboard, though, so stay tuned.

The Current Top Ten

Thanks for reading. I hope you’re warmed up after this first entry because I’m going to crank up the volume in the next entry with the heavy metal thunder of High on Fire. Until then, have a nice week.

Slipknot will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream, though not for any of the material that Jay Weinberg played on. No offense Jay, but you’re around my age, you know that my heart will always be with Joey Jordison.

Arcade Fire will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream.