Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each of them as I go. Once I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 455 songs to go!

This week I learned “The River” by Bruce Springsteen. This is the second Springsteen song in this series, the first being “Bobby Jean” which got this whole ball rolling exactly one year ago. I’m going to reference a handful of ideas from that inaugural entry in this letter, so if you haven’t yet read DU #1, consider doing so before scrolling on.

Let’s go down to “The River”.

Side A

“The River”

By Bruce Springsteen

The River

Released on October 10th, 1980

Liked on December 5th, 2015

I met “The River” in high school when I was just 17. My senior year English teacher assigned the song along with Joni Mitchell’s1 “River” as part of a lesson on literary metaphors. Being in my senior year of high school I was disinterested in taking this assignment seriously by default. I could be persuaded to work hard if the subject lined up with my personal interests, like in the "Propaganda & Protest" class taught by the same English teacher that prompted me to read 1984 and Brave New World for the first time, which in turn made me read V For Vendetta and watch Children of Men on my own time. What can I say, I had a real hunger for dystopian sci-fi as a teen. If a class didn’t spark the same fascination then good luck getting me to care. Bruce Springsteen and Joni Mitchell, firmly and conveniently gendered as “dad music” and “mom music” respectively, to say nothing of Springsteen’s unfortunate scoring of a doctor’s visit that nearly ended with two of my toes in a metal bin, fell well outside of that narrow field of interest.

My teacher asked the class to bring in lyrics to a song that used a river as a poetic device. The night before the assignment was due I searched my meticulously organized iTunes library for songs with “river” in the title and selected “No River To Take Me Home” by Neurosis. I was confidant that a band as seemingly somber and serious as Neurosis would provide me with a rich enough text to coast through my presentation with little effort. The next day, staring at the print-out of Neurosis’s lyrics, I realized I had made a grave mistake. Compared to the literary clarity and economy of Springsteen and Mitchell’s lyrics the Neurosis2 song read like burnout fridge poetry. I may not have appreciated the music backing “The River” or “River” at the time, but I readily appreciated how paper-thin Neurosis looked on the page without their muscular arrangements backing them up. With my “deep” art-metal thus revealed to be shallow, I slunk into embarrassed silence for the remainder of the class.

Years later, around the time Bruce Springsteen was playing The River in full on tour to support a new box set edition of the already lengthy double album, I realized the error of my ways. “The River” is an incredible song, one that depicts a dystopia far more distressing than any science fiction I read in high school and far richer in its complexity than any Neurosis song. The memory of flippantly dismissing “The River” just because it sounded like something old people enjoyed haunts me to this day. Now 15 years older myself (uh… wow) I want to make things right. Ben Miller-Callahan3, if you’re out there on that road somewhere, this one’s for you.

“The River” is the title track and final song on Side B of Bruce Springsteen’s fifth album, The River. Springsteen originally submitted The River to Columbia Records as a single disc collection under the name The Ties That Bind, but pulled the album because it didn’t feel “big enough”. Eventually he added enough songs, including “The River”, to match his ambitions. The River is indeed a big album, sporting 20 songs in over 80 minutes. But unlike Songs in the Key of Life, which I covered in DU #22, The River doesn’t earn its length through a kaleidoscopic range of styles and genres. Instead The River operates in two distinct modes: lizard-brain-dumb rock’n’roll party tunes (not an insult) and subdued folk songs about the desperation of working class life. “The River” falls squarely in the latter category.

You might assume from that description that “The River” is an autobiographical work. Not so. While fans have speculated that the song was inspired by Springsteen’s sister’s marriage, “The River” is best appreciated as a fictional character-study. Despite what some well-paid charlatans might tell you4, this lack of lived authenticity does not prevent “The River” from being a heartbreaking work of art. On the contrary, Springsteen's distance from the subject matter and his sleight-of-hand as a songwriter only make the song more powerful. Springsteen sings “The River” from the perspective of an unnamed narrator, born in an unnamed part of the United States, who impregnates and then marries his high school sweetheart, a turn of events that force him to work a dead end construction job while his marriage decays into unspoken dysfunction. That’s three “un”’s in one sentence. For all of the verisimilitude that Springsteen grants “The River” through his band’s arrangement and the raw power of his vocal performance, his lyrics are light on specifics. This is by design. Instead of building a movie set out of local color, Springsteen paints in broad enough strokes for the audience to complete the picture themselves. The sleight-of-hand is that these broad strokes appear at first glance to be granular details.

Take ‘The River”’s setting for example. All we have to go off in the first verse is a working class town in a valley, a literal depression, with limited career options. We can infer from the narrator referring to the audience as “mister” and using old-timey idioms like “that’s all she wrote” that this town is pretty far off from the less polite pace of an urban city. And of course we know that the town is within driving distance of a river. This is geographical ambiguity on par with The Simpsons’ Springfield. Springsteen could be singing about any small town in the United States, which is of course the point. By the time he brings up the Johnstown Company, placing us in Pennsylvania approximately, the audience has already filled in the gaps with a town of their own. Springsteen tricked you into doing the world-building for him.

Springsteen’s economy of detail isn’t just a ploy to win over the audience, it also shades in the outline of “The River”’s narrator. By holding back on specifics, Springsteen performs as a man with little left to say about his life. “The River”’s narrator, let’s call him Joe, is trapped in a hell of his own memories and only opens up enough to offer gruff short hand. Joe’s rugged straight talk is a cover. Springsteen pokes holes in his lyric’s facade by putting all of the unexpressed pain into his voice. On paper “the economy” could mean anything, but Springsteen sings it like one word can hold everything on earth that Joe has no control over. Eventually these perforations tear Joe wide open. In the song’s final verse he admits that he does remember and cannot stop remembering the days before his life turned to shit. What haunts him isn’t just the distance from those better days but the foreclosure of his future. Any chance for Joe to have been someone else with a different future has dried up along with the river.

The core question that my senior year English teacher posed to us all those years ago was “what does the river represent”? For a long time my answer would have been love. Springsteen implies that the river is where Mary’s baby is conceived, the river is where Mary and Joe go after they marry, and it runs dry by the time their lives have ossified. Now I think differently. The river isn’t love. The river is time. The river dries out because time has run out for Joe. Time rolls on and sweeps us along with it to an inevitable destination. It rolls on until who we used to be and who could have been mingle as ghosts in our memory. And in rock and roll, time is driven by drums.

Side B

“The River”

Performed by Max Weinberg

117 BPM (approx)

Time Signature: 4/4

When I learned Max Weinberg’s drum part for “Bobby Jean” last year I came up with a needlessly complicated term to describe his style: “Declarative Forward Momentum”. What I was trying to describe was the way Weinberg uses his kick drum to drive into the next measure while also making every downbeat super clear. The effect of all of these “and 1! and 3!” kick drum hits is that his grooves feel like they’re constantly pushing forward while also remaining static and stable. Weinberg uses this kick pattern all over The River. The kind of people who think Ringo Starr and Lars Ulrich are the worst drummers in the world (you know, morons) might see this as a lack of creativity or ability on Weinberg’s part. I see it as humility. Weinberg plays a part that works with a lot of Springsteen’s music instead of chasing the cheap glory of playing fresh parts for each tune. The song is king, and Weinberg guards the king like a knight of the round table.

Even if the kick pattern on the “The River” isn’t bespoke, Weinberg’s playing shows a deep level of attention to the arc of the song. After a verse of just Springsteen and an acoustic guitar, Weinberg enters and pushes the tempo up a couple of notches, kick-starting Joe & Mary’s inevitable descent. For most of the song Weinberg holds himself back, playing a cross stick instead of a snare and only playing fills to transition from one section to another. Even his fills feel fine-tuned for the moment, stretching out when he wants to build momentum and keeping it short when the song’s energy needs to recede. Weinberg’s real masterstroke comes in the final verse. Typically Weinberg times his fills around Springsteen’s vocals, making sure not to crowd out the words. On the couplet “I act like I don’t remember/and Mary acts like she don’t care” Weinberg breaks this habit and punctuates the word “care” with a crash cymbal. Then, as Springsteen builds to the song’s emotional peak, Weinberg brings in the snare drum. After holding back for so long this small change makes a world of difference. Watch my performance below, and you can read the power of that shift on my face.

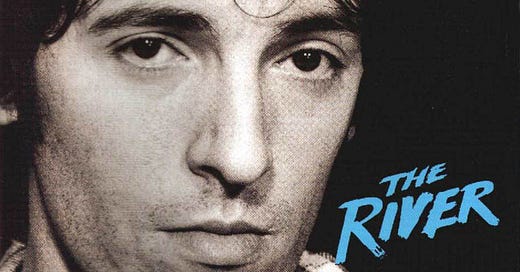

For this video I pulled out my green flannel and left the top button loose in my closest approximation to Springsteen’s outfit on the cover of The River. Can’t go wrong with flannel for Springsteen. Like “Bobby Jean”, “The River” was not recorded to a click but sticks to a tight enough range of tempos that you never feel the song speed up or slow down. The biggest challenge for me was actually holding back the way Weinberg does. In “Bobby Jean”, the final stretch of the song is where Weinberg lets loose, playing against the song’s climactic saxophone solo. No such release on “The River”. After the tight snare roll halfway through the final chorus Weinberg sticks to the groove. There is no triumph at the end of “The River”, only the steady creep of time passing ever forward.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

While writing about “The River” I stumbled on a rubric for what makes a song great rather than just good. In a great song, every part of the music makes every other part better. By this measurement “The River” is unequivocally a great song. The acoustic guitar and harmonica bring the song’s setting to life. Springsteen’s vocals enhance his lyrics. His lyrics make Weinberg’s consistent pulse part of the song’s overarching metaphor about the passage of time. There is nothing about “The River” that doesn’t make the rest of “The River” better. This puts it into rarified air on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard, above even Springsteen’s first appearance in the series and firmly in the top five.

“The River” by Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Springsteen will appear in Drumming Upstream several more times, but for now we’ll move on to a track by a younger artist that mines autobiographical experience to similarly stirring end. Until then, I hope you have a nice week.

Joni Mitchell would have appeared in Drumming Upstream if she hadn’t removed her catalog from Spotify in 2021 during the Neil Young vs Joe Rogan anti-vax fiasco. I won’t reveal which song was originally in my Liked list, but it wasn’t “River”. Cool song, though.

Neurosis will not appear in Drumming Upstream, which feels like a narrowly dodged bullet considering how much I like some of their material and how much former singer/guitarist Scott Kelly’s recently admitted abuse of his wife and kids disgusts me.

I went to the kind of high school where teachers encouraged us to refer to them by their full name instead of honorifics.

In case it is not clear, I’m calling Malcom Gladwell a charlatan, not Tyler Mahan-Coe. TMC is a legit great podcaster when he wants to be and his research skills put this whole newsletter to shame. Gladwell on the other hand is a moron who once argued that Steve Nash, a white Canadian, should play on the Nigerian national basketball team because he was born in South Africa. Sure, Malcom, and I’m a Peruvian writer because I was born in Brooklyn. I want zero smoke with Mahan-Coe, but Gladwell can catch me outside anytime.