Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 437 songs to go!

For this entry I learned “Adam Raised A Cain” by Bruce Springsteen. This marks the fourth time that Springsteen has appeared in this series, following “Bobby Jean” (DU#1), “The River” (DU#24), and “Backstreets” (DU#40). With a commanding 10% share of the Leaderboard, Springsteen is effectively the patriarch of the Drumming Upstream family, which makes it all the more ironic that this entry’s song is a vengeful blues rocker aimed squarely at Springsteen’s own father. What happens when the daddy of dad rock takes on dads themselves? Find out below!

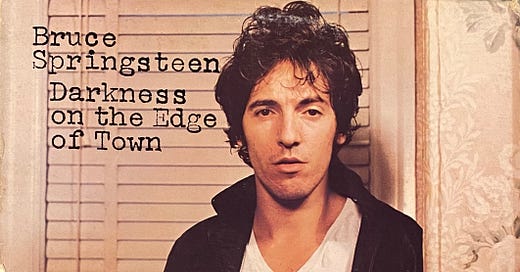

Side A

“Adam Raised A Cain”

By Bruce Springsteen

Darkness On The Edge Of Town

Released on June 2nd, 1978

Liked on February 29th, 2016

In 2019, just as Abraham had once bound Isaac for sacrifice, rock critic Rob Mitchum took the old saw about killing your darlings to heart and strapped his child to an operating table. 12 years earlier Mitchum had helped popularize the term “dad rock” in a review of Wilco’s Sky Blue Sky for Pitchfork, wielding the phrase to brand the alt-country band as washed up1. Not only had the term gotten under the skin of Wilco songwriter Jeff Tweedy, who called the description “unflattering and hurtful”, it had also, according to Mitchum, inspired a mountain of pop culture writing that slapped the prefix “dad” onto anything that could pin down. Mitchum, by then long removed from his days at Pitchfork and now a father himself, took to the digital pages of Esquire to examine what he had wrought on rock discourse.

The term dad rock means something different depending on, to paraphrase Arnold Schwarzenegger, who your dad is and what he does. In its most common usage however it refers to rock music from the middle of the 20th century, as opposed to rock music from the early days of the 21st. Even within this broadly accepted definition there’s room for different points of reference. In his dissection of the genre tag in Esquire, Mitchum notes that he picked it up from Chris Ott, Pitchfork’s Lucifer, cast out and damned to the fiery pits of Vimeo. Ott in turn nicked the term from British rock critics writing about bands from the early 1990s preoccupied with reviving the sounds of the 1960s British invasion. For Mitchum, whether defending the band or roasting them, calling Wilco dad rock meant that they sounded too much like American rock bands from the 1970s. In other words, mine to be clear, they sounded too much like Bruce Springsteen.

At least, that’s what the term dad rock means to me. Long before my peers convinced me to give Springsteen’s music an earnest try, I had filed The Boss under “stuff my dad likes” and dismissed him. I had heard enough Springsteen on long family drives, where The E Street Band’s horn section blasted loud enough to drown out the nü-metal CDs on my walkman, to write him off as hopelessly old school. I liked my fair share of 70s hard rock as a teen, but, despite a being contemporary of your Zeppelin’s Led and Sabbath’s Black2, Springsteen sounded much older than them. His music was too folksy, too self-consciously classic and reverent to the soda shop jukebox tunes of my parents’ childhood to fit with the raucous conception I had of “real” rock music. Or maybe I just hadn’t developed a taste for horn sections yet.

Had I heard “Adam Raised A Cain” sooner I might have had a different perspective. The second track on Side A of 1978’s Darkness On The Edge Of Town, “Adam Raised A Cain” is the first sign that Springsteen’s fourth album will live up to its title. Released three years after Born to Run launched Springsteen into real deal rock stardom and emphatically closed the early stages of his career, Darkness is the debut of Springsteen as we know him today. The songs and the lyric sheets are shorter, drained of the verbal and musical bloat of his early work. Instead the language and arrangements are lean, economic, and discomfortingly blunt. Darkness trades in starry-eyed romanticism for an unsparring look at what exactly Springsteen thought he was born to run from. And, perhaps most pertinent to today’s subject, it featured way, way more guitar.

The one thing that Springsteen didn’t trim down on Darkness was his sense of dramatic scale. Over a growling blues riff an industrial accident away from fitting right in on Masters Of Reality, Springsteen reaches for no less than the Old Testament for source material on “Adam Raised A Cain”. Or at least the Old Testament by way of John Steinbeck and Elia Kazan. As the story goes, according to The Book Of The Boss Chapter 4, Verse 2, Springsteen’s new-at-the-time manager and former rock critic Jon Landau started feeding Springsteen a steady diet of Woody Guthrie and John Steinbeck, hoping to push him to write with not just the crowd at the Stone Pony in mind but the whole of the American working class. Given Springsteen’s well documented habit of drawing from Hollywood, it’s no surprise that the early returns of Landau’s investment in his cultural enrichment would still yield something pungent with the rebellious musk of James Dean.

I haven’t read East of Eden, but a few weeks ago I joined some friends in their newly annual tradition of rewatching Elia Kazan’s 1955 adaptation every January. Dean stars as Caleb Trask, the moody, misunderstood, and preposterously handsome son of Adam Trask, a farmer in California’s central valley who bet big and lost big on refrigeration on the eve of America’s entry into World War I. Caleb, possessing none of his brother Aron’s pious devotion to their father’s bible-thumping morality, puts his good ol’ American opportunism to work, investing in bean farming just in time to cash in on the demand for war rations. Caleb tries to earn back his father’s losses as well as his love and respect. He gains the former at the cost of the latter two. In case the naming convention didn’t give the game away, things get much worse from there for the Trask family before Kazan offers his characters and audience a glimmer of hope in the tear-jerking finale.

To hear Springsteen tell it in stage banter and in the subtext of “Adam Raised A Cain’, selling his soul to rock and roll was about as incomprehensible to his father’s working class sensibilities as Caleb’s war profiteering was to Adam Trask’s Christian pacifism. The term “dad rock” would be incomprehensible to a 28 year old Springsteen, who had been a teenager during rock and roll’s first emergence as pop music. By 1978 the genre had only just been around long enough for the idea of rock for & by middle aged men to be possible, let alone popular. For someone of Springsteen’s age, appreciation of any stripe of rock music placed you firmly on the right side of a yawning generation gap. The anxiety that animates “Adam Raised A Cain” however, is that no gap is truly wide enough for Springsteen to separate himself entirely. Despite having, as Caleb did in East of Eden, returned home after making himself the wrong kind of man, Springsteen is haunted by the legacies that he cannot leave behind. Returning home means fitting into the role assigned to him at birth and “called by his true name” by his mother. His presence in turn forces his father to recall the tears he shed at his son’s baptism. Springsteen and his father damn each other implicitly. The Boss and his pops are “prisoners of love”, set at odds against each other by the mutual “hot blood burning in [their] veins”. Springsteen the younger must “inherent the sins” and “flames” of his father. Springsteen the elder must live with the suggestion lurking behind the song’s title that Cain’s violence is not some foreign body in the heart of man. Rather, it comes straight from the source.

This preoccupation with lineage might explain why “Adam Raised A Cain” sounds retro even by Springsteen’s standards. For this tune, Springsteen reached past the Spector-era sound of his youth to rock and roll’s oldest testament: the blues. The song’s blues signifiers are mostly surface level, this isn’t a 12-bar vamp after all. But the slow pentatonic riff, the wordless moaning at the song’s climax, and Springsteen’s nastiest lead guitar work to date all lend the song some old-time fire & brimstone. The end result is a sound closer to the mud of the Deep South than the Meadowlands, but on balance the song comes across as distinctly, but nonspecifically, American. In the same way that Springsteen’s choice of entry-exam-to-bible-school framing suggests that the song isn’t just about his dad but about all sons and fathers, its music claims that it isn’t just for ears on the east coast but for the whole union.

The Cinemascope breadth of Springsteen’s vision was self-evidently the right move. Though informed by Springsteen’s own complicated relationship with his real life father, “Adam Raised A Cain” succeeds because he understands that his issues are not his alone and are instead universal. This is great news for Springsteen’s bank account, but it leaves a disquieting impression for future generations. You see, Springsteen’s issues aren’t just universal across distance, they’re also universal across time. Even as successive batches of youngsters take up the guitar to wage war on their fore-bearers’ ears, they must contend with the uncomfortable likelihood of their fathers having done the same. This is why the term “dad rock” is so fraught. Springsteen’s anxiety on “Adam Raised A Cain” about the proximity of the apple to its tree also lurks behind any accusation of dadness hurled at a rock band. Implicit in the “genre”’s name is the acknowledgement that the rock of the present (son rock?) exists on the same continuum as the music it defines itself in opposition to. Even as the accuser attempts to stand apart, the term suggests that actually, you and your dad aren’t all that different, just off-set in time. And with that suggestion, a warning: your rock one day too will be affixed with the prefix- Dad. Time, relentless as the rain, will make it so.

Just ask Max Weinberg.

Side B

“Adam Raised A Cain”

Performed by Max Weinberg

94-98 BPM

Time Signature: 4/4

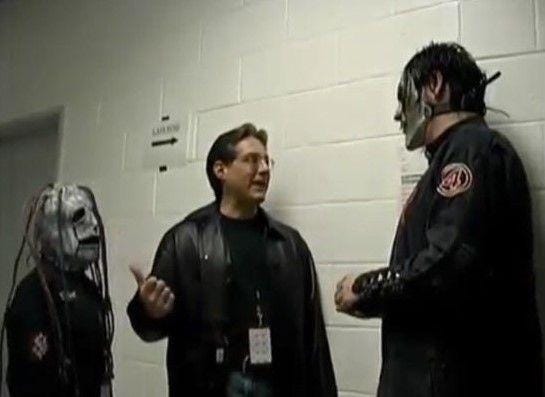

Just as I like to imagine how a young Springsteen would react to his music being filed under “dad rock”, I get a real kick out of picturing a young Max Weinberg hearing the racket that his son Jay would make a generation later. Could Weinberg the elder, while laying down the swaggering groove of “Adam Raised A Cain”, imagine the arms race that would lead his son Jay to don a serial killer mask and jumpsuit to play a song called “People=Shit” to millions of eager fans across the world? As generous as I’d like to be to the vision of those who preceded me in the business of rocking and rolling, I doubt anyone could have predicted the popularity, let alone the existence, of a band like Slipknot in 19783.

Yes, as I alluded to briefly in my entry on “Backstreets”, Max Weinberg’s son is also a drummer. Quite a talented and successful one at that. Unlike other second generation rock drummers like Jason Bonham or Zak Starkey, Jay Weinberg has shown no interest in joining the family business performing the E Street Shuffle. Instead, as any good elder millennial with a rebellious streak would, he chose the path of hardcore and nü-metal. I first heard about Jay Weinberg when he joined the long-running New York hardcore act Madball. Weinberg didn’t last long, (gee, I wonder why the son of a famous rock drummer didn’t gel with a bunch of rough-and-tumble working class guys from the Lower East Side?), but he quickly rebounded and, after an equally brief stint playing with Against Me!, filled the literally small but figuratively huge shoes of former Slipknot drummer Joey Jordison. Though I have little affinity for late period Slipknot, the band having settled into their own equivalent of dad rock years ago, Weinberg had no trouble rising to the occasion. Weinberg raised hell in Slipknot for nine years until he was unceremoniously fired in 2023, roughly around the time he was recovering from a surgery that would keep him off the kit for months. This is something of a pattern for Slipknot, who also let go of Jordison around the same time he was diagnosed with a debilitating nerve disorder that kept him from touring. Come on, Clown, if the Chicago Bulls can keep employing Lonzo Balls two years after he last stepped foot on a basketball court, you can give the drummer some R&R.

I’m sure Jay Weinberg is doing just fine, coming as he does from generational drummer wealth on top of his own presumably sizable Slipknot earnings. Still I find myself sympathetic to Weinberg, perhaps because of how neatly he and his father’s careers map onto my own experience of the rock generation gap. I’ve got a homemade Corey Taylor mask in my childhood bed room almost identical to the one he’s wearing in the picture above. I imagine its even harder to hear your favorite nü-metal albums over The E Street Band when they’re in the same building as you. Despite his son playing for some of the most “mad at your dad” sounding bands on earth, Max Weinberg is fully supportive of Jay’s career. Still, when compared to the macho simplicity of “Adam Raised A Cain”, I wonder if Slipknot’s nine man cacophony strikes Max Weinberg as a little embarrassing.

Though “Adam Raised A Cain” is not a metal song I didn’t make the allusion to Black Sabbath earlier just for fun. Weinberg goes harder on this track than any of the previous tunes I’ve learned by him. The scaled back arrangements on Darkness on the Edge of Town give the drums a lot more room to fill the gaps. Even though this tune is a solid two minutes shorter than “Backstreets”, Weinberg fits in just as many distinct grooves and nearly twice the number of fills. Not only are there more fills, Weinberg builds those fills out of a wider array of ingredients than any of the other songs of his I’ve learned, mixing together long triplet rolls on the snare drum and quick flurries of 16th notes in between cymbal accents along with his typical preference for slow, multi-measure tom fills. My favorite of the bunch is maybe the simplest. Half way through the second verse Weinberg throws in a quick two note fill on the kick drum in a gap where no one else is playing. It feels mischievous, like he’s hoping Bruce doesn’t notice him getting away with something showy.

The grooves on the tune aren’t radically different, but the minor changes all serve a purpose. Weinberg’s beat in the intro and choruses match the rhythm of the guitar note for note on the kick drum with an extra hit thrown in for good measure. In the verses he eases up to give more space to the lyrics. The most important change comes in the pre-chorus, where Weinberg switches to a pounding four-on-the-floor kick pattern and adds eighth notes on the hi-hat, building momentum as Springsteen winds up for the chorus. All of this variety on the kit, taken in tandem with the band’s hooting & hollering in the background of the track, gives “Adam Raised A Cain” a rowdy and unruly character. One for the boys, to be sure.

As you can imagine, it also makes the song a lot of fun to play.

For this cover I wore my Semaphore long sleeve because it features an image of Shinji Ikari, patron saint of boys with daddy issues.

If you’re wondering why a fourth Springsteen followed so quickly after the third, well part of it is that I Liked “Adam” only a few days after Liking “Backstreets” back in 2016, but more importantly it’s because the more Max Weinberg parts I learn, the easier it is to learn more Max Weinberg parts. For example, I saw the inevitable third verse twist coming a mile away. This time around Springsteen cuts the third chorus short to return to the pre-chorus before launching into the genuine final chorus of the tune. I’m also starting to intuit where Weinberg likes to start his fills, when he pushes the tempo and when he lays back, etc. I’m even starting to adapt to the physicality of his playing. Locking into his grooves has a way of correcting your posture. It’s funny that this song is nearly identical in tempo to “Backstreets” because the two couldn’t feel more different on the kit. “Backstreets” felt like playing in a musical, where I had to follow the lead of the singer and pianist. At the risk of sounding self-aggrandizing “Adam Raised A Cain” felt like practicing with Lamniformes. Heck, maybe I should start practicing “Adam Raised A Cain” with Lamniformes.

Does the song’s resemblance to my own tunes mean a higher placement on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard? Find out below.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

When I finally decided to listen to Bruce Springsteen with an open heart it took me a while to find a way into his discography that didn’t make me feel like I was playing dress up with my dad’s ties, or worse, giving into the pressures of classic rock radio. As self-centered as it sounds, I needed to find my Springsteen, some foothold in his towering body of work that I could cordon off as separate for the rest of his myth. As silly as it sounds considering the album’s immense popularity, Darkness and “Adam Raised A Cain” were that foothold. It helped that even among my Springsteen enthusiast friends that “Adam Raised A Cain” wasn’t particularly popular, and that it’s low & slow biblical heaviness put it in approximately the same musical universe as the stuff that I’d built my whole personality around. I opened this draft expecting the song to leap frog the rest of the Springsteens that I’d learned. As much as I love “Adam Raised A Cain”, and I do love it, I couldn’t bring myself to put it over “The River”.

Springsteen hadn’t quite gotten the hang of his new sparse lyrical style in 1978. Maybe the most Black Sabbath thing about “Adam Raised A Cain” is the way Springsteen rhymes “name” with “names”. As compelling as I find the biblical stakes of the song’s angst, and as fun as it is to lay into its fat groove, it’s hard for me to argue that it’s a better work than the haunting pessimism of “The River”. For now that puts “Adam” in the top ten, but just outside of the top five at a respectable 6th.

The Current Top Ten

“Adam Raised A Cain” by Bruce Springsteen

Thank you for reading. In the next entry I’m going to switch lanes from dad rock to dad rap to discuss the Brooklyn hip-hop duo Gang Starr. Until then, I hope you have a nice week!

Wilco will not appear in Drumming Upstream, but their frequent touring guitarist Nels Cline will.

Black Sabbath will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream. Led Zeppelin will not.

Slipknot will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream.