Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 446 songs to go!

In this entry I learned “Kassidat El Hakka” as performed by Sexwitch, a short lived collaboration between Bat for Lashes and the band TOY. Sexwitch in turn learned “Kassidat El Hakka” from a recording by Abdellah el Magana. By covering this cover I waded into deep and murky waters, where neither the song’s rhythm or its authenticity are clear. Can I navigate safely to the opposite shore? Find out below.

Side A

“Kassidat El Hakka”

By Sexwitch

Sexwitch

Released on September 25th, 2015

Liked on October 21st, 2015

In the waning days of Twitter’s relevance I came across a new remembrance of a bygone era. Someone named Jack Fernandez posted a collection of album covers all from the year 2009 along with a request that someone explain, preferably by video, how so many noteworthy records dropped in one year. If you were paying attention to indie rock all of those years ago you can probably rattle off each of the albums without looking at the original tweet. Merriweather Post Pavillion by Animal Collective. Bitte Orca by Dirty Projectors. Veckatimist by Grizzly Bear. That one The xx album. The famous Phoenix1 record. And then, down at the end of the the list I saw an album that surprised me. Two Suns by Bat For Lashes.

There’s nothing factually inaccurate about including Two Suns, the second full length from British singer/songwriter Natasha Khan, in this collection. It did in fact come out in 2009 and it fits comfortably into the so-broad-its-functionally-meaningless category of “indie”. However if we comb with finer teeth Khan’s music hardly resembles the work of her Class of ‘09 contemporaries, especially the trio of Animal Collective, Dirty Projectors, and Grizzly Bear who took up most of the airspace that year. While those three drew from the psychedelia of the late 60s and the elaborate precision of 70s prog rock, Khan’s points of reference were a hair more modern, repackaging 80s new wave and synth pop for post-Donnie Darko hipsterdom. There are other noteworthy differences. Those other three bands are all helmed by white American men, whereas Bat For Lashes is a solo project by a British, half-Pakistani women. And, one could argue relatedly, while Two Suns was critically praised (Best New Music, etc) that praise never felt as effusive or caveat-free as the praise headed to AnCo and co.

I never spent much time with most of the records Fernandez tweeted about. In 2009 I was lost in the music school sauce and only had ears for the most brazenly virtuosic guitar music I could get my hands on. A few years later when my taste balanced out a bit I did, however, spend a lot of time with Two Suns. My recovering myopia likely helped Two Suns make a positive impression. A self-described perfectionist, Khan builds songs around her voice with the attention to detail of a miniature diorama. The craft is always self-evident on a Bat For Lashes song, either in the piecing together of so many disparate, pretty sounds or in the faithful recreation of her influences. Then Khan inhabits those dioramas with the verve of a stage actor. No surprise that someone like me, trained on the fussy theatrics of progressive rock, would find Khan’s studious approach to pop music so appealing.

But even after giving Bat for Lashes my public seal of approval with a positive review of 2012’s The Haunted Man on a friend of mine’s now defunct blog, I understood why Khan’s music never earned the same widespread adoration as her peers. Studious, perfectionist, theater kid pop will always be too mannered and self-serious for some, especially those looking for danger or spontaneity from their record collection. Khan’s best work either has sturdy enough melodies to compete on a party playlist or leans all the way into her theater kid instincts. Anything caught in between risks coming off as too stuffy and try-hard.

Apparently Khan herself started to feel the same way. While working with producer Dan Carey2 on The Haunted Man, the two bonded over a shared interest in kraut rock and psychedelia. They started digging through record stores together, pulling out compilations of folk songs from around the world, the more seemingly obscure the better. Carey then recruited the British psychedelic rock band TOY to cover their favorite picks in quick, one take sessions. Khan finished the job by improvising vocals with lyrics translated into English. With no chance to tinker endlessly, Khan let herself loose, howling, chanting, moaning, and screaming with an abandon absent from any previous Bat for Lashes record.

“Kassidat El Hakka”, the third track of the resulting collection of covers and the longest of the bunch, is the best argument for this looser approach. Over a churning low-end shuffle that ebbs and flows for nearly eight minutes, Khan works herself up to a state of pure expression, repeating snatches of the translated lyrics until she drops language altogether for ecstatic wailing, cackling laughter, and a hair-raising scream. Its likely this combination of pleasure and terror, which Khan described after the fact as “funny sex noises”, that inspired her to name the short-lived project Sexwitch.

This self-consciously goofy name was well timed. Sexwitch arrived in stores just months before Robert Egger’s The Witch and a year before Anne Biller’s The Love Witch arrived in movie theaters. The proliferation of pop feminist media in the 10s brought along with it a parallel interest in darker, edgier forms of feminine power. Even gross boys like me could get in on the fun. After I saw The Witch in theaters I listened to all of Sexwitch on my way back home while vicious winds raged through downtown Chicago and had a good time doing so. From the interviews I’ve read with Khan about Sexwitch, I gather that she had a good time too. She seems genuinely psyched about the freedom that Carey’s rapid pace granted her, describing the album as the closest she’s coming to performing jazz and relishing at the chance to work with a malleable live band instead of her usual meticulous arrangements. There’s something charmingly old school about a singer recording with a backing band barely familiar with the material, cutting the first good take, and moving on without overthinking the results.

The only problem was Khan and Carey’s choice of canvas for this free-ranging expression. Sexwitch features two songs from Iran, two from Morocco (including “Kassidat El Hakka”), one from Thailand, and one from the United States. Prior to stumbling across them on their crate-digging adventures, neither Khan or Carey had any sentimental attachment to the tunes. “We’re kind of ignorant about the music that we’re using as starting points”, Dan Carey told The Guardian in an interview from September 2015, presumably aware that the purpose of the interview was to entice people to listen to Sexwitch. I respect Carey for his honesty, better than bullshit I suppose, but his foolhardiness makes me wince. To be so brazenly disinterested in the origins of your covers in 2015 is to pogo stick onto a pile of rakes. Concepts like cultural appropriation, exoticism, and orientalism were a matter of well-known and feverish debate by this point, especially among the college educated types that might have listened to Two Suns in 2009. Carey, much like his recording ethos, seems stuck in the 1970s, happy to replicate the most played out psych rock cliches of Brits inspired by the mysterious East.

Carey’s run-and-gun ethos put Khan in a difficult position as the public face of the project, and thus the person most likely to be asked to justify its existence. So charged in both Pitchfork and The Guardian, Khan defended her choice of material in two ways: first by appealing to the authority of her Pakistani heritage, describing fond memories of the music her father played when she was a child and claiming that music like Sexwitch’s is “in her blood”, and secondly by saying, essentially, that artists should be allowed to do whatever they want. Neither argument was able to dissuade critics from tearing into the record. Zohra Atash, singer of the excellent synth pop duo Azar Swan, practically nuked Sexwitch from space in a review for Talkhouse, taking Khan to task for flattening the diverse vocal traditions of Asian music into Disney-ready exoticism. “If [Sexwitch] were a celebration of ancestry,” Atash, who is Afghani, writes, “then Khan would come from the land of Agrabah”. Yowza!

I’m obviously in no position to judge whether Khan’s connection to the music she chose to cover is authentic, and I’m not as well-versed in the styles of singing that Atash cites to say whether her takedown is fair. What I can safely say is that regardless of whether Khan’s desire to connect meaningfully with music of the Middle East and Northern Africa is sincere, that desire runs at cross purposes to her desire to make quick, uncomplicated music. In fact, I’d readily believe that Khan wanted to reconnect with her musical roots and wanted to get loose to horny, druggy rock music. Desiring both sincerely doesn’t make those desires compatible.

If Khan and Carey had done their homework they’d have had a much greater opportunity to honor their sources accurately, but that would have defeated the project’s anti-perfection ethos. It is of course possible for an artist to improvise authentically in the styles and musical languages that Khan claims affinity with, but only if the performer has years of experience with the music in question. Absent that experience Khan’s instincts led her to familiar tropes, of “dark girls” in exotic locales unleashing their power through trance states and “funny sex noises”. Khan’s attempts to play the project off as tongue-in-cheek makes it seem that she finds the very heritage she’s attempting to honor to be a bit of a joke.

The conflict between these two desires, for authenticity and for the simple pleasures of rocking out, never resolve on Sexwitch, leaving the album’s best song, “Kassidat El Hakka” to strain between the pull of two contrary forces. Which is, as it so happens, a great way to describe how to play the song on drums.

Side B

“Kassidat El Hakka”

Performed by Charlie Salvidge

90-96 Bpm

Time Signature: 4/4 & 6/8

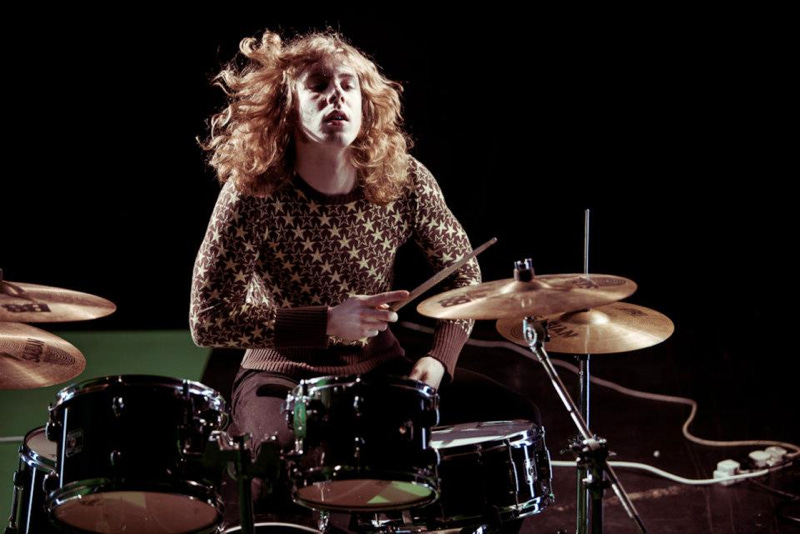

I haven’t said much about TOY, the band that serves as Khan’s backing band on “Kassidat El Hakka”, because there isn’t that much to say about them. In the years since learning about their existence from the liner notes of Sexwitch I’ve never encountered them anywhere else. They have reliably cranked records of kraut rock, 1960s psych rock, and 90s shoegaze without adding meaningfully to any of those styles for the last decade. Look, I’m not judging, throw me an album faithfully recreating 90s death metal and I’ll be happy as a clam for about 40 minutes. All I’m saying is that TOY have made it pretty easy for me to be incurious about their career as long as I have access to actual records from the 60s, 70s, and 90s. Still, as far as backing bands go, I think Carey made a good choice by tapping TOY for Sexwitch. They clearly know how to think on their feet, have good chemistry, and can cook up the right heady blend of sounds for trance-inducing jams without getting too lost in the sauce. The key to that sauce navigation is drummer Charlie Salvidge, whose sturdy and nonintrusive playing keeps TOY in time and on track.

Natasha Khan might have been the reason I heard “Kassidat El Hakka”, but Salvidge and TOY are the reason I Liked the song. They offer both the clearest link back to the original recording, repurposing Abdellah el Magana’s flute melody on guitar, while also pushing the song into entirely new territory. In the original the flute melody and el Magana’s voice call and respond to each other. TOY take that melody and turn it into a maddening loop then send it tumbling downhill with a powerful shuffle rhythm. This shuffle, which Salvidge pounds out on his toms, is TOY’s primary contribution to “Kassidat El Hakka”. They must have known they struck gold because they didn’t bother adding anything else to the track. The band chug along at this rhythm on and off for nearly eight minutes, occasionally stopping to let Khan vamp over Carey’s Swarmatron synthesizer. Some instruments drop in and out, but otherwise TOY are relentlessly, hypnotically, consistent.

There’s only one wrinkle, but it’s a big one: Salvidge’s snare. After the song’s second verse, Salvidge changes his drum part to include his snare drum, giving the song a jolt of energy while also making it significantly more complicated on a rhythmic level. You see, the song’s central melody is made up of six eighth notes. Salvidge’s toms hammer out a pattern where every other beat is emphasized like “ONE-two-THREE-four-FIVE-six”, which makes for a pretty straight forward 6/8 groove. The problem is that starting in the third verse Salvidge plays his snare on every other quarter note. From his perspective he’s just playing a straightforward 4/4 shuffle, accenting beats two and four. No one else in the band makes this change, leaving the two implied time signatures to clash against each other.

This tension is exactly why I Liked “Kassidat El Hakka”. Playing 6/8 and 4/4 at the same time GOES HARD. Salvidge’s on-the-fly decision to change time signatures turns the song into an act of seduction, coyly drawing you in with one rhythm only to sweep you off your feet with another. The brilliance of this double-sided rhythm is that it gives you something familiar in an unexpected place. Even if you didn’t see it coming, your ears know exactly how to catch on to a 2 & 4 backbeat. The mind boggles, but the body responds. Don’t just take my word for it, listen to how Khan reacts when Salvidge brings the snare back after a prolonged absence at 5:46 on the studio recording. In about as heavy handed a way possible, the, uh, re-entry of the snare is what brings the song to its climax. I won’t lie, the first time I got the timing right on the reintroduction of the snare I blushed self-consciously.

For this video I wore my Azar Swan t-shirt, because like everyone else in this entry I am trying to have it both ways. You’ll notice I’m also drenched in sweat. The air conditioner at my practice space was busted when I learned this song. It has since been fixed. Stay hydrated.

When it came time to learn Salvidge’s polyrhythmic shuffle, I immediately found a way to make it even more complicated for myself. Instead of playing alternating strokes with my hands on my rack and floor tom, which would have let me easily move my right hand to play my snare drum, I decided to stick the groove as RLRRLLRL so that I could play the back beat with my left hand. Playing it this way required more coordination, but it allowed me to ride the song out on both floor toms without any awkward movement. Basically I craved more low end and made the song harder to play in order to get it. I also took the time to mark down ever single one of Salvidge’s fills. There are only fifteen total, which in an eight minute song makes of their absences conspicuous. By treating his improvised performance as if it were a written part, I probably ended up rehearsing “Kassidat El Hakka” more than TOY did. This is the problem with recorded music. No matter how quickly you set a song to tape, the results can be puzzled over for the rest of history. Luckily, I enjoyed playing along with Salvidge’s shuffle enough to make zeroing in on his details a pleasurable experience.

How does the tension of my criticism of “Kassidat El Hakka”’s origins square against the pleasure I got from playing it? Find out below on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

“Kassidat El Hakka” has always felt like a relic on my Liked list. I Liked the song months before I read Zohra Atash’s take down of Sexwitch. After reading the review while researching Azar Swan for an interview, I was never able to hear the song the same way again. Try as I might to focus purely on the sonic pleasures of “Kassidat El Hakka” I couldn’t shake the specter of Atash’s criticism. Suddenly everything that felt spontaneous and wild felt ill-considered and slapdash. Maybe it’s just because I’ve been reading Thus Spake Zarathustra while working on this cover, but I’m sympathetic to Khan’s attempt to radically reinvent her creative process and to embrace an embodied, physical style of singing in the process. If anything, my frustration with Sexwitch lies with Carey, whose concern for one kind of authenticity put the authenticity of the rest of the album on shaky foundations. Ultimately everything good (Khan’s vocal performance, Salvidge’s polyrhythm) and everything bad about “Kassidat El Hakka” stems from Carey’s fetishistic need for fast recording. With more time, maybe at the very least they’d have ended up with a shorter song. Eight minutes is a long time to ponder complicated issues of cultural exchange.

Weighed down by its length and ill-considered implications, “Kassidat El Hakka” sinks to number 29 on the Leaderboard, below Joyce Manor’s “Constant Headache” (DU#3) and Stella Luna’s “Antares” (DU#29).

The Current Top 10

After the last few entries of wrestling with songs that I have conflicted feelings about, I’d like to spend the next entry playing and writing about a song that I have nothing but positive things to say about. Until then, thank you for reading and I hope you have a nice week.

Phoenix won’t appear in Drumming Upstream, but their drummer Thomas Hedlund’s other band Cult of Luna have appeared once before (DU#17) and will appear again many times.

Not to be confused with Danny Carey, the drummer of Tool.