Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 444 songs to go!

This week I stepped away from my drum kit to consider “Still Life”, an abstract electronic piece by the prolific composer Daniel Lopatin, a.ka. Oneohtrix Point Never, one of the most critically acclaimed electronic artists of the early 2010. How does his music hold up a decade later? Find out below!

Side A

Still Life

By Oneohetrix Point Never

R Plus Seven

Released on September 30th, 2013

Liked on March 10th, 2016

“-is that-”

Those are the only two words that appear in “Still Life”. They are some of the only words that appear at all on R Plus Seven, composer Daniel Lopatin’s first album for Warp Records under the name Oneohtrix Point Never. These two words, presumably a sample, fly by so quickly that it is next to impossible to extrapolate what phrase they could’ve been snatched from. Removed from their original context they serve no clear grammatical purpose. They could be part of a question (“What is that?”) or part of a statement (“Daniel Loptain is that dude”) depending on how you choose to hear them. Both of those hypothetical statements are appropriate reactions to “Still Life”, a piece of music equally capable of bewildering and amazing its audience.

Perhaps to fill the void of words available on the album itself, critics heralded the arrival of R Plus Seven with more reviews than any other record I’ve researched for Drumming Upstream. There are non-musical explanations for the glut of writing. There may never be more active blogs on the internet than there were in 2013 when R Plus Seven first dropped. The record followed Oneohtrix Point Never’s major critical breakthrough Replica (2011), which made Lopatin the hottest name in the experimental wing of electronic music. A push from the hard working publicists at Warp turned that hype into a furnace of analysis, especially since Lopatin’s Gen Y points of reference spoke directly to a new generation of digital native critics. However persuasive these arguments are though, there remains something intrinsic to R Plus Seven on a musical level that demands analysis and explication. Even the album title reads like a high school algebra problem. Solve for R.

This is how I first heard of and heard Oneohtrix Point Never, not as music to be enjoyed for its own sake but as a puzzle to be worked over, considered, and, with enough effort, solved. Fresh out of music school in 2013 I considered myself up for the task. I quickly realized that despite my technical qualifications I was woefully unequipped on a conceptual level to tackle Lopatin’s music. I could pick out the underlying melodies and chord structures but I couldn’t for the life of me tell you what Lopatin was using them to do. I could tell that there was some artistic logic at play, I just couldn’t decipher it. Left out in the cold from the party that the rest the critics at the time were enjoying, I filed Oneohtrix Point Never away as an artist that I respected but couldn’t yet enjoy.

Eventually Lopatin began to meet me halfway, first by opening for Nine Inch Nails1 and then by releasing the gooey, digital nü-metal freakout Garden of Delete in 2015. A few bounce riffs was all it took for me to crack Lopatin’s impenetrable style. Encouraged, I decided to give R Plus Seven another shot, which is how “Still Life” ended up on my Liked list in early 2016. I don’t always recall the circumstances of the moment when I hit Like on a song, but I remember exactly where I was, what I was doing, and which part of the song inspired the Like for “Still Life”. On March 10th, 2016 I had just stepped out of the Blue Line Station on Ashland & Division in Chicago. It was late at night and I was waiting to transfer to the Ashland bus heading south to Pilsen, where I lived at the time. Almost immediately after stepping out into the night air “Still Life” swelled out of near silence into a cascade of descending arpeggios and booming sub-bass. Despite having heard the song many times by this point, I was floored and immediately opened up Spotify to Like the track.

Several critics singled out this moment in “Still Life”, which kicks in three minutes and eleven seconds into the track. Sasha Geffen described this moment as “an action sequence score complete with cyberpunk sound effects” for Consequence. Ryan Alexander Diduck called it “a swirling trap rhapsody” in his review of R Plus Seven for The Quietus. Both of these descriptions ring true, but they might give you the idea, if you’re unfamiliar with Chicago, that I had stepped out of the train into some colossal neon-streaked metropolis. Let me assure you, Ashland & Division is no such thing. This train station and bus stop sit at the intersection of three different streets and at the edge of at least three neighborhoods. This transit hub has no identity of its own. It is a place between places, a bland way-station that you pass through without truly inhabiting. There’s a shoe store, a CVS, a parking lot, a Verizon outlet, a Potbelly’s and a furniture store that looks like sells bedbugs wholesale. In recent years a few hideous condos have sprung up around the intersection, but back when I lived in Chicago the most exciting feature on the block was a night club called evilOlive. One cold night waiting for the bus I watched eleven identical lime green sports cars circle the block to pull up at evilOlive as if someone were copy-pasting them onto the road. A year after I moved back to New York evilOlive got shut down after a security guard got shot.

In the years since Liking “Still Life” I’ve never been able to figure out why I remembered this moment with such sharp clarity. What was it about this setting that has stuck so firmly to my memory of this track? After reading probably too many reviews of R Plus Seven and contemporary interviews with Lopatin I think I might have a satisfying answer. But first let me bring you up to speed on Oneohtrix Point Never.

Daniel Lopatin, child of Russian immigrants and musicians (his mother a musicologist, his father a composer), grew up in Wayland, MA an hour’s drive east of Boston. Lopatin received piano lessons from his mother and inherited his father’s Roland Juno-60 synthesizer. After moving to Brooklyn to study Data Archiving at Pratt, he put both to use by writing his own music. Taking on the name Oneohtrix Point Never, a play on Boston’s soft rock radio station Magic 106.7, Lopatin released short batches of these ambient instrumentals online and on cassette in the late 00s. Along with these increasingly sophisticated adventures in analog synthesis, Lopatin experimented with sampling, looping and manipulating short snatches of songs from his late 80s childhood into surreal ambient drones that he uploaded under the pseudonym Chuck Person, named after the former NBA player (Lopatin, regrettably, is a fan of the Boston Celtics). These “Eccojams”, along with similar work by artists like James Ferraro, spurred a whole subculture of online musicians toying with the uncanny effect of chopped & screwed 80s adult contemporary and commercial music which fans and critics dubbed “vaporwave”.

Lopatin’s true breakthrough came with the Oneohtrix Point Never album Replica, composed out of sampled advertisements. From there it was off to the races. Lopatin collaborated with Tim Hecker2, scored Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, and signed to Warp Records. In the years since releasing R Plus Seven his star has only continued to rise. He scored more movies, 2017’s Good Time and 2019’s Uncut Gems both directed by the Safdie Brothers, and collaborated with pop/pop-adjacent singers like The Weeknd, Anohni, and James Blake3. Lopatin now operates on a Wagnerian scale, throwing massive “world-building” events at Park Avenue Armory and music directing The Weeknd’s Super Bowl halftime performance in 2021.

With hindsight’s clarity, R Plus Seven is the pivot point between Oneohtrix Point Never, cult figure and Oneohtrix Point Never, Certified Genius™. Like many such transitional records it represents both a culmination of and a clean break from the work that preceded it. While clearly informed by his experiments with sample collage and synthetic sound design, Lopatin abandoned his typical process and his usual instruments. Instead of building his material around samples Lopatin came up with motifs from scratch like a traditional composer (“such a cheesy process”) and then fed them into MIDI instruments that imitated the sounds of organs, choirs, and other orchestral instruments. Once he’d archived enough raw material he set to work arranging them into discrete pieces.

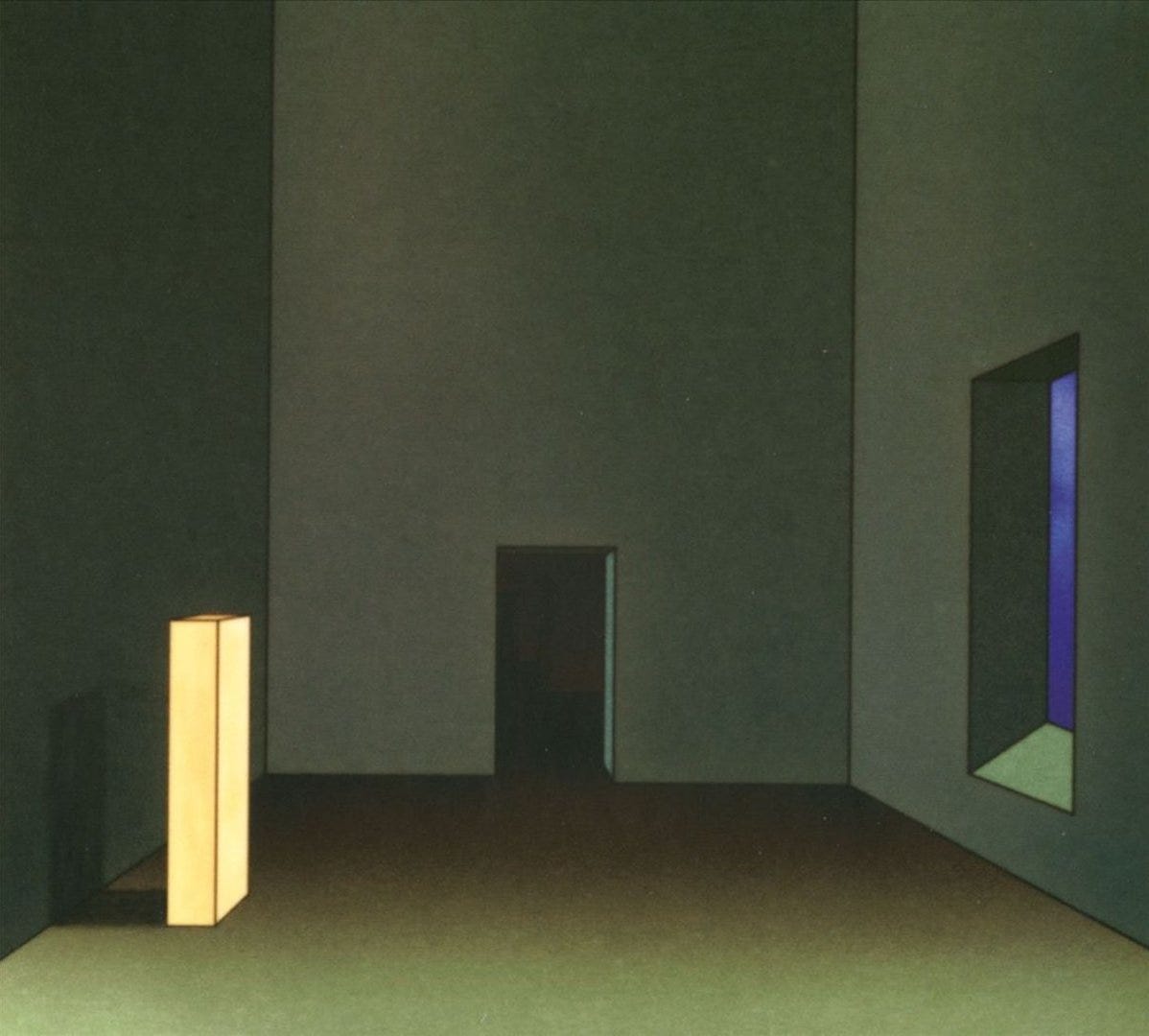

The end result are tracks like “Still Life” that don’t resemble songs so much as sonic sculptures. If you listen to the song expecting sections that function like traditional verses or choruses you’ll leave sorely disappointed. Each of Lopatin’s melodies and sonic gestures happen independently of each other, often cutting each other off at sharp angles with no regard for traditional phrasing. This style can be so disorienting that it is easy to miss how pretty the record is. Lopatin might have found the process of sitting down at a keyboard and waiting for inspiration to strike cheesy, but he was inspired nonetheless. Still, no matter how pleasing Lopatin’s melodies are on paper, once filtered through his sound font they take on an eerie, uncanny quality. Like much of the record “Still Life” is built on digital facsimiles of the human voice, as well as some palpably fake sounding pianos. Lopatin makes no effort to hide this artificiality, no one occupying a real physical space could sound like that while singing, but your ears still try to hear them as the product of living, breathing people.

Over and over in the interviews that I read Lopatin compared his process to that of a sculptor. He thinks of these tracks not as songs but as objects that can be observed from different angles. The various changes that take place in each track are analogous to the way that a sculpture looks different when viewed from a different perspective. “Still Life” calls direct attention to this way of listening in its title. We’re aren’t hearing something that changes over time, we’re observing a static image. The title also works as a description of what that image is made out of. The choirs are, essentially, life that has been rendered still, sapped of all of their human and spiritual connotations and reduced to pure sound. No matter how pretty the shape these post-human sounds have been molded into, there’s something inherently disquieting about hearing the human voice as an object. Things only get freakier from there. With a physical sculpture the observer gets to choose how to view the object, when to change angles and which direction to move in. Music doesn’t work that way. Because “Still Life” moves through time linearly, only Lopatin can control how we experience the song across time. We can’t stop and study a single detail or reverse course. We are trapped in Lopatin’s point of view, just as frozen and still as the “voices” his object is built from.

The aggressively NSFW video for “Still Life”, directed by Jon Rafman, makes this final implication of the piece’s title explicit. Rafman guides the viewer through the internet’s subbasements, cutting between fetish art and grossly neglected keyboards and desktops. The internet satisfies desire and creates new desires at an unprecedented rate, to the point of paralyzing its observers in a feedback loop of desire and satisfaction. It’s only once you unplug yourself from the loop that you can recognize how hollow that satisfaction is. Step back from the screen and the internet’s true nature appears.

When I was a teenager I’d often spend long nights surfing the web after everyone else in the house had gone to bed. I’d cycle through a number of different forums, following links out to anything that struck me as remotely interesting or novel. I’d scroll through social media feeds long after anyone I knew was posting actively. I referred these aimless strolls through the internet to myself as “searching for god” half-jokingly, half-dead serious. I knew that whatever deeper meaning I was searching for would never appear, but I kept plugging away in the hopeless belief that I would stumble upon some connection that would put all of the information flowing through me into a concrete order. But there is no order. There is no solving for R. No context for the broken shards of human speech that litter the web. The internet is, at best a place between places. A land of dead links populated by the digital equivalent of fast food restaurants and outlet stores that sell you viruses whole sale. Everything dangerously alive is bulldozed and replaced by hideously tacky architecture. You can never inhabit this space. You can only observe it and be frozen in the process.

Lopatin’s “swirling trap rhapsody” at the heart of “Still Life” is, in this light, a moment of shocking and overwhelming clarity, a pulling away of perspective to reveal the true shape of the object that it emerges from.

With that mystery solved we can move on to the true question of the day: theory aside, just how good is “Still Life” anyway? Find out below on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

I’ll be honest, when I started drafting this entry I expected to bury “Still Life” deep in the lower rungs of the Leaderboard. I considered my affection for the track’s climax as a matter of lizard-brain weakness where the simple pleasure of hearing a big, loud synthesizer overwhelmed my sense alienation from the overall composition. I knew that I would emerge at the end of the draft with at least a richer appreciation of Lopatin’s methods and vision, there’s simply too much writing on the subject to not walk away with more than I came in with, but what I didn’t expect was that as I was researching R Plus Seven short snatches of melody from “Still Life” would sneak into my brain and stay there.

Despite all my notions about the track’s cold abstraction, it slowly began to warm up and make itself at home. I’ve grown fond of the song, especially the final moments after the crescendo that initially hooked me. I love how the choirs and the brittle piano play off of each other. I enjoy the bewildering effect of playing a human voice like a piano. And yeah, that sub-bass drop flat out rocks. I still prefer music that adheres closer to recognizable structures, but I’m nowhere near as put off by Lopatin’s style as I once was. And, if I’m being honest, I found the process of trying to solve “Still Life”’s more inscrutable aspects fun. I’m just built like that, I guess. That’s enough to put “Still Life” at a respectable #24 on the Leaderboard.

The Current Top 10

Thanks for reading. For the next entry I’ll return to the kit to take on a high energy hardcore anthem from the Canadian punks in Comeback Kid. Until then, I hope you have a nice week!

Nine Inch Nails will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream multiple times, as will Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross’s non-NIN soundtrack work.

All three of The Weeknd, Anohni, and James Blake will appear in Drumming Upstream, though not for their work with Lopatin.