Welcome to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 442 songs to go!

This week I learned “Mercy.1”, a smash hit from the summer of 2012 featuring Big Sean, Pusha T, Kanye West, and 2 Chainz with production by Lifted and a number of other producers. Does the song add up to more than the sum of its parts, or is it dragged down by its creator’s legacy? And just who’s song is it anyway? Find out below.

Side A

“Mercy.1”

By Kanye West

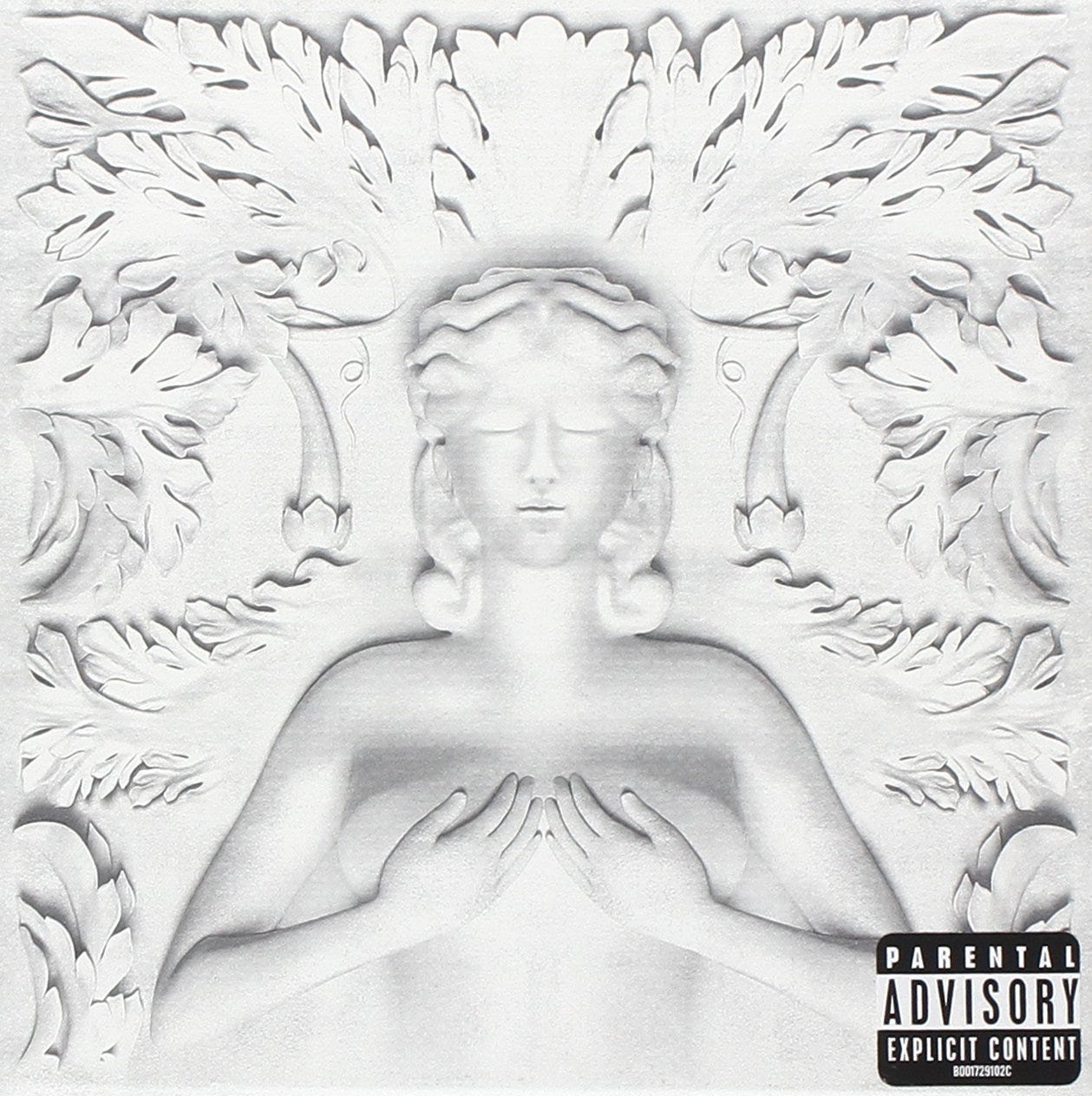

Cruel Summer

Released on September 14th, 2012

Liked on January 28th, 2016

Whose song is “Mercy.1”?

The official answer is Kanye West, the now disgraced superstar rapper and producer. When we last saw West in this series he was behind the boards for Jay-Z’s “Takeover” (DU#19) in 2001. A decade later West was one of the most famous and critically acclaimed musicians in the world. By the summer of 2012, when “Mercy.1” was unavoidable on rap radio and at college parties, West was on the second bend of a multi-year victory lap. He’d weathered the storm of bad PR following the 2009 VMAs fiasco, won back critical support and public good will with 2010’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and then doubled down by co-headling 2011’s Watch The Throne with his former mentor Jay-Z. Determined to keep the good times going through 2012, West released five singles in advance of Cruel Summer, a compilation meant to show off the roster of West’s G.O.O.D. Music label. As the first and most successful of these five singles, “Mercy.1” was received without question as part of Kanye’s rapidly expanding body of work.

Calling “Mercy.1” a Kanye West song might be technically correct, but it is also a reduction with odious consequences. The strange irony of West’s three year run to start the 2010s is that the higher his star rose, the less direct of a presence he seemed to have in his own music. He raps only one of “Mercy.1”’s four verses, with a few ad-libs sprinkled in for good measure. He’s one of at least four credited producers on the track (more about the producers on Side B). Even with the implicit understanding that the song is an execution of West’s vision, listening to “Mercy.1” involves hearing the work of a lot of other people. One of Kanye West’s greatest strengths was his ability to surround himself with interesting people, at least until his definition of interesting veered sharply into psychedelically incoherent fascism. “Mercy.1”, released long before that dark turn, was meant to showcase that exact curatorial skillset, but it wouldn’t have taken over the summer without the contributions of the rest of the ensemble. Ye may be the reason for the season, but he didn’t deck the halls.

The trouble with reducing “Mercy.1” to just the product of Kanye’s genius is that it obscures the work rest of its team and chokes out conversation about the song’s merits with the noxious fog of Kanye’s reputation. Hence the two paragraphs of air clearing. So while we could talk about how “Mercy.1” fits into the grand narrative of Kanye’s rise and fall, I think we’d all have a lot more fun if we left the true ownership of “Mercy.1” as an open question. Based purely on the song itself, who does “Mercy.1” belong to? If I’m being honest, mulling over this kind of question is half the fun of songs that feature multiple rappers, colloquially called “posse cuts”. Collaboration invites comparison. Something deep in the human mind craves to be asked “Choose your fighter”. Pick your favorite color Power Ranger. Select your most delectable critter in Pokémon. Declare who had the best verse under threat of forever being a cornball. Luckily for us, “Mercy.1” has something for everyone. Each rapper brings something distinct. Do you prefer the pinchable-cheeked pretty boy smarm of Big Sean, the “real” rap precision of Pusha T, Kanye West’s egocentric bombast, or the bulldozing charisma of 2 Chainz?

My personal preference has changed over the years. The first time I heard “Mercy.1” in April 2012 I had Kanye tunnel vision. I had dismissed Kanye West as crass loudmouth for years until I heard My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy in college. Being the kind of student who had double under-lined “Gestamtkuntswerk” in my music history notes, I was an easy mark for Kanye West’s multi-media venn diagram between art and public relations. I had no genuine interest in West’s professions of attraction for suicide doors, designer drugs and his new girlfriend, wife-to-be and then not-to-be Kim Kardashian, but I was happy to nod along as long as he made them over a “Wagner at Berghain” beat switch AirDropped into the track from the heavens. The substance mattered less than the profundity that it alluded to. Did the dual meaning of mercy, alluding to the divine and to a Lamborghini in the same phrase, actually mean anything, or did it just suggest that there was a greater meaning?

Only a few months later I realized that the only appropriate answer to that question is “who cares?”. “Mercy.1” isn’t a good song because it provokes thought. It is good because it is fun. In the early days of the summer of 2012, I joined Bellows on my first ever tour, a two week trip that went as far south as Murfreesboro, Tennessee before looping back north through Ohio up to Massachusetts and then back home. The three of us, Oliver, Felix, and myself, packed ourselves and our makeshift gear into an ancient Toyota Camry and hurtled down the highway with only the vaguest idea of what we were doing. Somewhere on the southward leg we got into the habit of making that Camry throb with “Mercy.1”’s 808 powered bassline every time we entered a new city’s limits. It was our private ritual to pysch ourselves up for the night’s show, made marginally public by the decaying construction of the vehicle. It didn’t take too many cities to have Big Sean’s opening verse memorized.

If you’d asked any of us in the car during these two weeks what we thought of Big Sean we would have rolled our eyes in unison. The youngest rapper on the track and the freshest face in the G.O.O.D. Music lineup, Big Sean was, and remains, really annoying. Prior to “Mercy.1” Big Sean had built his name on pop radio-friendly raps littered with the pickings of low-hanging fruit. Over beats that could have been plucked from the leftovers of the Lasers sessions, Big Sean bombarded listeners with lazy puns and pickup lines that wilted without his winning smile to back them up. It is music whose greatest ambition is to be booked at end of the semester parties at state colleges.

Landing the lead-off spot on a blockbuster posse cut was a huge look for Big Sean. To his credit, Big Sean chose to be himself and only partially rose to the occasion. Big Sean begins his verse with four consecutive ass puns, each more strained than the last, and things only get dumber from there. It is the sort of verse that actively defeats critical thought and it’s all the better for it. Sure, it looks stupid on paper and sounds just as stupid coming out of Big Sean’s mouth, but it is extremely fun to yell “Built a house up on that ass, that’s an ass-state!” in a car with a bunch of your friends. Big Sean’s verse is a reminder that underneath all the pseudo-religious imagery and austere black and white cinematography “Mercy.1” is supposed to be a good time.

We ran into a number of bad times on that 2012 tour. Our car broke down twice. Our GPS led us into a road that had long been grown over by trees and rocks.1 We had to endure one host’s awful songs about God before going to bed after a show. However, when I think back on those two weeks I mostly remember the good stuff. We met Frank “Friend of Music” Meadows for the first time, and he’s in Bellows now! We played for kids attending a farming camp and got to hang out with a bunch of animals. One host cooked us steak dinner after an abysmal show in Covington, Kentucky. And most of all I remember yelling Big Sean lyrics at the top of my lungs as we pulled off the highway.

Four years later, around the time that I Liked “Mercy.1” on Spotify, my allegiances had shifted. Had you asked me who my favorite rapper was, as many of my coworkers did to kill time at the venue we worked at, I would have said Pusha T. Formerly half of the duo Clipse2, the coke rapper and fast food jingle veteran’s career caught a powerful second wind in the 2010s after he hitched his sails to Kanye West. Over the course of the decade Pusha T established himself as the country’s most popular unpopular rapper, whose Hemingway-esque economy and singular pursuit of a single theme (the trials and spoils of selling drugs) made him a hard sell to the general public but a pet favorite with critics and dedicated rap fans. His team up with West was mutually beneficial. Pusha T granted G.O.O.D. Music hard-edged gravitas, while West supplied him with the slickest production on the market.

While nowhere close to the fighting shape that he’d find by the decade’s end when he became the first rapper to crack Drake’s impenetrable public image3, Pusha T lends a similar legitimacy to “Mercy.1”. If Big Sean’s “just happy to be here” goofiness put you off, Pusha T’s verse is meant to reel you back in. Pusha T doesn’t ride “Mercy.1”’s beat so much as chop against it. Even after two weeks of practice, none of us in the car had a chance of keeping up with Pusha T’s fleet-tongued syncopation and mercurial rhyme schemes. While the content of his verse isn’t substantially different from the rest of the song Pusha T brings an artisanal craftsmanship to its presentation. In a song otherwise devoted to getting heads nodding and car doors rattling, Pusha T’s verse is red meat for rap fans dedicated to rewinding and decoding every passing line. It isn’t enough for him to rap about an expertly designed watch or sports car, Pusha T pays the luxury forward by delivering a verse just as rich with excessive detail. If you can’t work out what “these blue dolphins need two coffins” means, your pallet might not be sophisticated enough for the rest of the menu.

While Pusha T’s verse is the most technically accomplished of the four on “Mercy.1” even he will admit that the song doesn’t belong to him. “I had the more intricate lines” Pusha T told Peter Rosenberg in 2012, “[but] I watch people totally spazz for 2 Chainz”. Ten years later he was even more emphatic: “2 Chainz had the best verse on ‘Mercy’”. In an informal poll about “Mercy.1”’s best verse on my Instagram, my followers concurred, giving 2 Chainz a whopping 60% of the vote.4 In the present day, 11 years after I first the song, I’m inclined to agree with the masses.

Having spent years as peripheral player in the Southern rap scene performing under the name Tity Boy, the newly rechristened 2 Chainz recorded his verse for “Mercy.1” in the middle of a career altering flow state. I don’t think a single one of my casual rap fan friends had heard of 2 Chainz before “Mercy” dropped, but by the end of 2013, following the barrage of “Birthday Song”, “I’m Different”, and “Talk Dirty To Me”, everyone knew him by voice alone. That voice, an unhurried Georgia drawl, is a massive part of 2 Chainz’ appeal, especially on “Mercy.1”. He sounds completely at home on the song’s slow rolling groove, and with three verses already on base he brings Braves-worthy power to the clean up role.

2 Chainz takes the best parts of each verse before his and rolls them into 10 bars of pure gold. Unlike Big Sean, 2 Chainz is actually funny. His verse is a conveyor built of punchlines that fall just to the right side of the thin line between stupid and brilliant. It took me an embarrassingly long time to notice the pun in “I’m drunk and high at the same time, drinking champaign on an airplane” and when it hit me I felt like 2 Chainz had just pulled a quarter from behind my ear. Unlike Pusha T’s verse which calls attention to its labor-intensive meticulousness, 2 Chainz sounds effortless and off the cuff, as if he’d thought of the whole verse on the spot. Apparently he did.. And like Kanye, 2 Chainz delivers his verse with mic-shattering confidence. Despite having the least time in the spotlight 2 Chainz steals the whole show. Kanye’s superstardom and meta-textual antics may have made “Mercy.1” an event, but 2 Chainz made it an enduring hit and a classic piece of early 2010s pop culture.

Of course, Lifted had a big part to play in “Mercy.1”’s success, so let’s flip sides and dig into the track’s production.

Side B

“Mercy.1”

Produced by Lifted

70 BPM

Time signature: 4/4

As I mentioned on Side A, there are a number of credited producers on “Mercy.1”. Kanye West gets a credit, as does frequent West collaborator Mike Dean and erstwhile TNGHT member Hudson Mohawke. However, all signs suggest that Lifted, one of G.O.O.D. Music’s in-house beatmakers, is responsible for the song’s foundation and its hook. Calling “Mercy.1” a Lifted song would be just as much of a reduction as calling it a Kanye West song. To be certain the Fuzzy Jones sample (a collaboration between Twilight Tone and Kanye West) and the four-on-the-floor bridge (my bet is Mike Dean, judging by the synths) are a substantial part of the song’s identity. I’d like to focus on Lifted because for one, its his drums that I had to learn to play, and because his melodic and sampling choices set the tone for everything that follows.

“Mercy.1” is all about downward motion. The song begins with a three note descending pattern, landing lowest on each quarter note, that repeats for nearly the whole track. Each new instrument joins this loop in its perpetual downward motion. All of this descent pulsing on each quarter note gives “Mercy.1” a grave seriousness, a sense of imposing power and opulence. Think that’s a stretch? Consider the theme from Succession, also built from constantly falling resolutions and also meant to invoke its characters’ staggering wealth and influence. Something about this much downward motion gives the song a tragic inevitability and haughty superiority. It sounds like wearing all black to play against a team you despise, or opening the door to discover someone has pre-arranged your funeral march. Tone & West’s Fuzzy Jones sample is the perfect compliment. Instead of locking into the pulse, the sample wobbles in loose triplets while describing the jealous anguish of the haters in the language of scripture.

Lifted’s other key contribution is the pitched sample that gave “Mercy.1” its name. As he explains in the video above, Lifted took an isolated sample of the rapper YB and “screwed” it, referring the Houston tradition of slowing down and rhythmically stuttering a sample. While Lifted may have been thinking specifically of Chopped & Screwed music when he added that sample, the choice helped “Mercy.1” resonate with a number of concurrent trends in pop music. The early 2010s had seen a massive boom in the popularity of dubstep, and consequently EDM in general. Dubstep and EDM producers both got a lot of milage out of chopping pre-existing vocals into pitched percussion or catch-phrase ready hooks. That practice quickly spilled out into the rest electronic pop production, as you may recall from my entries on the Scottish Synthpop band Chvrches (see DU#20 & DU#30) or even the parallel explorations in atomized human voices conducted by Oneohtrix Point Never (see DU#35) or Holly Herndon5. Point being, vocal chops were very hot in the early 2010s, and putting one in “Mercy.1” helped it slide into the rap and EDM versions of trap playlists.

Lifted is also responsible for “Mercy.1”’s drums, which, well let me play them first.

Honestly, the drums are probably the simplest part of the whole song. Lifted did not over think this. With the exception of Kanye’s verse, the drums on “Mercy.1” are a single bar loop. Sometimes there are hi-hats, other times there aren’t. This is, and I say this with all love, the perfect drum beat to teach beginner students. The 16th note hi-hat pattern will test a student’s consistency and the kick pattern will help develop their syncopation at a nice and slow tempo. Learning this song properly mostly required me to remember the places where Lifted removes the beat, each chorus works differently which is a nice touch, and to remember to have fun. So I had fun! Even during the Kanye part, which I expected to cringe through. Turns out it feels badass to play two floor toms like marching timpani. I had so much fun that I even let myself solo during the last repetition of the chorus, something that I’m usually too self-conscious to indulge in. If I only had to interface with “Mercy.1” behind a drum kit it’d be among the most carefree experiences I’ve had with Drumming Upstream. Sadly, as you’ll see on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard below, I must consider it from behind a keyboard as well.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

“Mercy.1” is the second song about a car that I’ve covered in Drumming Upstream, following Todd Terje’s “Deleoran Dynamite” (see DU#7). Since I’m an insufferable city slicker who grew up around public transportation that works decently well when it isn’t filled with water, I never made the effort to get a driver’s license. In an effort to leave no stone unturned in my research and to make up for my lack of car knowledge, I brushed up for both of these covers by watching clips from Top Gear about the vehicle in question. One observation from a clip reviewing the Lamborghini Murcielago in 2006 jumped out to me. “The only we reason we liked Lamborghini is that they’re silly, taking that away is like taking the sunshine out of a summer holiday.” Eight years earlier Lamborghini had been purchased by Audi, who then tried to marry their more sensible design philosophy with the gaudy sports car aesthetics of the Lambo. This conflict between luxury and accessibility got me thinking about Kanye West’s short lived collaboration with Gap, where he tried to replicate his high fashion interests on a mass market scale. Recalling this made me realize just how much else had happened and changed since 2012.

Looking back its clear now that Cruel Summer was a tipping in Kanye West’s career. Here is the moment when Kanye West, famous musician, began to be overshadowed by Kanye West, famous famous person. It begins here, Kanye embracing his heel-turn, the Kim Kardashian romance that fed him directly into the Los Angeles Reality TV ecosystem, the emphasis on hastily made, deliberately unfinished work supported by a too big to fail scale of presentation. Letting this wave of disappointing history wash over me I returned to the song with a new question. Has Kanye West, by his subsequent actions, taken the silliness out of “Mercy.1”? Not entirely. The 2 Chainz verse gets me as hyped as ever. I still associate the song with one very good summer, full of misadventure and abundant with possibility. However, much of that possibility has now settled into immutable fact. Kanye West’s pursuit of ever grander stages for his art took him to some dark and poisonous places. I don’t blame “Mercy.1” for that, but I can’t help but know the road it is driving down.

Taken in balance, I’d put the song at No.23 on the Leaderboard, not great, not bad, just O-O-O-O-O-OKAY.

The Current Top Ten

Thank you for reading. Next week I’ll be stepping away from the kit again to return to the subject of Julianna Barwick, who last appeared in Drumming Upstream #11. Until then, have a great week!

These two incidents were immortalized in the Lamniformes song “Deep Despair in Covington, KY”

Clipse will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream.

Drake will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream.

Big Sean came in second with 20%, Kanye trailed with 13% and Pusha T came in last with 7%.

Holly Herndon will eventually appear in Drumming Upstream with a relevant example.