Welcome back to Drumming Upstream! I’m learning how to play every song I’ve ever Liked on Spotify on drums and writing about each song as I go. When I’ve learned them all I will delete my Spotify account in a blaze of glory. Only 436 songs to go!

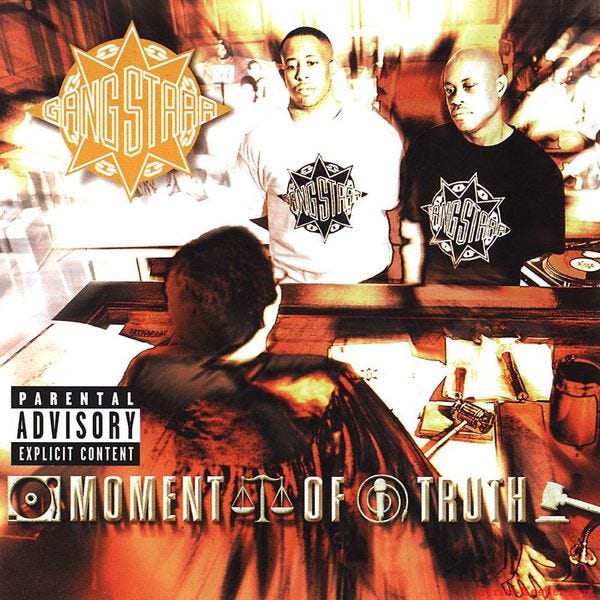

In this entry I covered “Moment of Truth” by the 90s New York rap duo Gang Starr, a song that arrived when rap’s soul was at the crossroads between the mainstream and the underground. What makes this song a rap classic and an indelible part of the sound of New York City? Find out below.

Side A

“Moment of Truth”

By Gang Starr

Moment of Truth

Released on March 31st, 1998

Liked on March 23rd, 2016

Living in New York City it would have taken a herculean feat of willful ignorance to miss that hip-hop turned 50 last summer. Thanks to an extensive publicity campaign from the City and consideration of the milestone in local media, the genre’s semicentennial has entered the realm of common knowledge. This is fairly unique. I can think of no other genre of music whose origins are so firmly tied to a place and time as to be a matter of consensus. Other genres get to show up with new haircuts and new IDs to sneak back into the club, but hip-hop is firmly middle aged as a matter of public record. It is a strange fate for hip-hop, given how strongly the genre is associated with youth culture, but knowing its age comes as a necessary side effect of honoring its past as well as it does. While in the mainstream the genre is propelled by successive waves of 19 year olds flooding in ready to Logan’s Run anyone born a few months before them, rap’s underground has long had an equally strong current of veterans with clerical reverence for the old ways.

Today’s cover concerns one such case from the year hip-hop turned 25, when, after a prolonged absence, the rap group Gang Starr released their fourth full length album Moment of Truth. Much had happened in rap and to rap since the pair of Keith “Guru” Elam (the MC) and Chris “DJ Premier” Martin (the DJ) had last joined forces. Between 1994’s Hard to Earn and 1998’s Moment of Truth rap had seen the supernova emergence and subsequent tragic killings of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G.. Audiences grew, and their tastes changed. West coast “gangsta” rap and its jazzy “conscious” counter-programming were either being phased out or overshadowed by glitzy artists aiming for radio domination. In the same span of time Guru and Premier had turned 37 and 32 respectively. Returning to find rap more popular than ever but with its identity in flux, the duo were happy to play the old guys in a new world.

In the two entries of Drumming Upstream I wrote about Bruce Springsteen earlier in the year I described how Springsteen belonged to the first generation to grow up on rock and roll and the first to age into what’s since been dubbed “dad rock”1. Gang Starr occupy a similar position in hip-hop’s chronology. Guru and Premier were both children when the first hip-hop parties were popping off in the Bronx. As teens growing up in Boston and Houston respectively they were so taken with early rap records that as young adults they both moved to New York City to devote themselves to hip-hop. As with Springsteen and rock music, growing up in tandem with rap made Gang Starr true believers in the genre’s principles and potential. This made them the perfect team to lay down the law on rap realness in the genre’s late 90s transitional moment. That might sound hyperbolic, but I’m hardly embellishing on Moment of Truth itself. In one spoken word skit that we’ll discuss a length on Side B, DJ Premier proclaims Gang Starr as torchbearers of real hip-hop in the darkness of posers faking the funk. In another, just before the album’s second track “Robbin Hood Theory”, Elijah Shabazz implores Guru to use his skills to pass on his values to the youth, whether that be religious faith, “old schoolism or new schoolism”.

Gang Starr didn’t just believe that hip-hop itself has values that need to be heeded, Guru rapped with the conviction that the genre could provide lessons applicable for the rest of life. In fact, Guru’s lines aimed at lesser MCs often arrive as nonsequitors in verses otherwise devoted to down-to-earth storytelling. You can almost hear Guru’s eyes snap to the back of the classroom to make sure that the punks are taking notes on the rest of his lecture. Guru is hardly the only rapper to impart street smarts or use the genre for consciousness raising, but no one delivered those messages quite like he did. Guru dubbed himself “the king of monotone” on “Moment of Truth”, but unlike previous Drumming Upstream subject Vince Staples2 whose flat affect lets him blend into the background of his tracks, Guru uses monotone as a pedagogical tool. Guru never put extra emphasis on any word in his flows and never let the pace of the beat hurry his delivery. He often strolled right over the bar line to add an extra rhyme even if it put him behind to start the next scheme. It’d sound awkward if he didn’t rap with such understated confidence. Never sounding showy or athletic, Guru’s off-kilter simplicity has a way of catching you off guard and sticking with you after the track fades out.

Guru’s distinctive flow is also a case of teaching by example. Guru’s unfazed, unbothered delivery combined with his weathered baritone evince stoic resolve under pressure. This isn’t just a pose for the recording booth either. In 1996 Guru was busted for possession of a firearm at Los Angeles International Airport. According to DJ Premier in a 2018 interview, Guru recorded the first two verses for “Moment of Truth” while awaiting trial and returned for the third after getting cleared. While the first two verses concern Guru’s reckoning with the law and the stresses of the industry, his third flips the script and puts the soul of hip-hop on trial. That Guru sounds exactly the same with a sentence weighing over his head as he does relieved of that burden speaks volumes to his even-keeled persona on the mic.

Still, it’s not like Guru is some invulnerable John Wayne tough guy. After lamenting the backstabbing and resentment behind the scenes in the music industry in the first verse, Guru shifts to an introspective mood without even the slightest change in his tone. He never mentions the court case directly, but Guru is frank about the state it has put him in. “Now I’m contemplating in my bedroom pacing/Dark clouds over my head, my heart racing” Guru raps before confronting his worst impulses. After considering escape into drugs and drink, or worse violence against himself and others, Guru snaps back and finds the strength to carry on. “I’m ready to lose my mind but instead I use my mind”. Guru’s conclusions, that doing drugs will only make him feel worse and that this current hardship too will pass, aren’t going to break any academic ground. But this plainspokenness is part of their appeal. Guru isn’t lecturing his listeners from a place of moral superiority. His direct language makes him seem all the more relatable, which makes it all the more possible for his audience to imagine themselves overcoming similar situations in their own lives.

In “Moment of Truth”’s third verse Guru reveals that this direct approach is by design. “While others struggle to juggle tricky metaphors/I explore more to expose the core”. With the earned gravitas of his first two verses, Guru uses the song’s final stanzas to challenge his contemporaries to live up to his standard. Guru is just as blunt when assessing the rap scene as he is taking stock of his own struggles. “Most MCs are stupid to me/and we have yet to see if they can match our longevity.” Anyone can jump on a trend and get hot for a few months, the track implies, but the only way to last as long as Gang Starr had by ‘98 is to deliver real substance in your music. Again, Guru doesn’t get didactic. He doesn’t say how other rappers should carry themselves or what they should or shouldn’t rap about. Instead, as with his flow, he leads by example. Forget the flashy gimmicks and multi-syllabics; tell the truth or face it.

Hip-hop has endured for 25 years more since Guru took the stand, though he didn’t live to see the last 14 of them. Guru passed away in 2010 at the distressingly young age of 48. This untimely death has cursed “Moment of Truth” with an eerie melancholy. To close out the song’s second verse, Guru stands defiant against the cards life has dealt him:

“They can’t take the respect that I’ve earned in my lifetime/And you know they’ll never stop the furious force of my rhymes/…/So I pray, remembering the days of my youth/as I prepare to meet my moment of truth”

Hip-hop’s generational divide has deepened in the years since Moment of Truth, most starkly between older fans who can identify a pager and digital natives born after the genre’s supposed “golden age” had already ended. If Gang Starr were the old guys in ‘98 they’re ancient history now. But ancient history is still history. Guru and DJ Premier achieved exactly what they set out to do when they moved to New York. Inspired by the early classics of hip-hop they in turn became the classics for the next generation. Aging into “Dad Rap” has only solidified Gang Starr’s stature. Dad rap is everywhere in New York. You hear it at ball games, over brunch, dinner, and late night drinks, at corner stores and sun-dappled boom boxes on stoops. Defy it or embrace it, but you can’t stop its furious force. Respect for Guru’s name has endured all the while, thanks in part to the efforts of DJ Premier. Premier has kept Guru’s voice alive, not only by assembling a final Gang Starr album in 2019 but by becoming a living icon of the hip-hop purity that the two strived for in their work. In some ways Premier has always spoken for Guru. What Guru’s even-keeled flow only suggests, Premier’s beats express in pure sound. And he may never have expressed anything quite so beautiful as the beat to “Moment of Truth”.

Side B

“Moment of Truth”

Produced by DJ Premier

90 BPM

Time Signature: 4/4

If the goal of this project was to highlight the drummers (broadly speaking) that have had the biggest impact on my playing in order of magnitude, I would have covered DJ Premier years ago. It is hard to quantify the influence of figures this massive in music history, but I can give you a concrete example. When COVID reached New York in March of 2020 my practice space shut down and didn’t re-open until the summer. With no access to a kit for months and a lot else on my mind, I knew that my touch was going to suffer when I picked up the sticks again. When I finally got back into the studio in August I didn’t drill rudiments or coordination exercises; I put on DJ Premier beats and locked in. The break had given me a chance to approach the kit with a clean slate. If I’m a better drummer now than I was pre-COVID, and I am, I owe at least some of that improvement to copying DJ Premier’s swing.

My reverence for DJ Premier’s production as a rhythmic foundation might be the most stereotypically New York thing about me. DJ Premier’s beats are as New York as a rat sharing a slice of pizza with Spike Lee and Fran Leibowitz. I could summon up all sorts of musical explanations for this. I could compare the sound of his kick drums to a basketball hitting hot concrete. Or I could make the more interesting argument that Premier’s use of white noise, scratches, and vocal samples simulate the constant blend of sirens, rattling trains, and music blasting from passing cars that crowd out silence in the city. As evocative as those arguments are, they’re getting the story backward. Premier’s resume is filled with some of the most well known and acclaimed New York rappers in the business. Nas, Biggie, KRS-One, Jay-Z, Rakim and more, all the way down to smaller acts like M.O.P. have all rapped over Premier tracks3. Those beats defined the sound of the city for a generation. How could they not stick to the softer edges of my memories?

This makes it all the more interesting to me that Premier grew up in Houston, Texas. My theory is that growing up outside of hip-hop’s epicenter gave him something more valuable than proximity. It gave him something to aspire to. Traveling to New York City over the summer to visit his grandfather in the late 70s, young Primo marveled at b-boys and DJs in matching jackets putting on a show on street corners. Had he been born in Brooklyn or the Bronx Premier may have gotten a head start on his participation in the rap scene, but the distance afforded him the gloss of romanticism. When he was old enough Premier packed up his mother’s vinyl records, presumably started spreading the news, and left to be a part of it in ol’ New York. Mother Premier, an art teacher, clearly had impeccable taste. By the early 90s Premier was turning those records into hard, minimal grooves for New York’s ascendant boom-bap scene.

To understand Premier’s sound it might be helpful to compare him to another producer of similar stature from the Drumming Upstream archives. DJ Premier is from roughly the same generation as No ID, who produced “Loca” for Vince Staples”, but of a completely different disposition. As I covered in DU#27, No ID changed with the times, moving to Atlanta as the South ascended in the 00s and then transitioning into an executive role in the 2010s. Now No I.D. produces Triple A serious-business albums for rappers as geographically diffuse as Vince Staples, Killer Mike, and Jay-Z. His stage name has in a sense become a mission statement. Premier on the other hand has stayed religiously devoted to his own sound. Even when called to work with stadium status pop stars like Christina Agulaira and Kanye West in the mid-00s, Premier arrived fresh out of bubblegum and fully loaded with boom bap drums and record scratches. Reading interviews with Premier about his process, you get the sense that he’s a zealot about his style. “I'm not just a fan,” Premier told NPR in 2019 about his efforts to preserve the old arts of hip-hop. “I'm in, culturally. ... It's a spiritual God, and I will not go against God, ever. When you do, the punishment comes.”

Like Guru says in the opening moments of Moment of Truth, Gang Starr have their formulas. Premier’s is pretty minimal. Kick, snare, hi-hats, all played with a distinct 16th note swing. There’s usually one main sample cut up into a two bar loop, and maybe a less prominent second sample to fill out the bass or add texture. Scratches in between verses for variety, salt to taste. Premier may not change the formula, but he does swap in new ingredients over time. When critics pigeon-holed him as a jazz rap specialist after the first three Gang Starr albums, Premier returned on 1994’s Hard To Earn with a set of beats that traded jazz harmony in for something closer to musique concreté without losing any of the well worn grooves. His drums always sound like drums, but everything else on the track could come from anywhere.

Like a lot of producers and DJs, Premier claims to a be a voracious listener across genres and I have no reason to doubt him. It’s a testament to Premier’s vision that no matter what he’s pulling from he always sounds like himself. His cuts are often so precise that it can sound like he’s hiding his tracks, shaving off just enough of the source material to make it untraceable. Producing this way is a pragmatic choice in a litigious world, but for Premier in 1998 it was also a matter of staying true to hip-hop’s ethos. At the end of “Royalty", Moment of Truth’s fourth track, Premier stops the music to decry the mainstream music industry practices seeping into underground hip-hop. He singles out Strictly Breaks, a vinyl compilation series that collected songs sampled on hip-hop records with annotated liner notes naming names, for “violating, straight up and down!”. The issue is bigger than just avoiding lawsuits. Sample snitching was seen as giving away the game, taking the fun and art out of beat making.

As much as I love liner notes and credits, I see where Premier was coming from here. Focusing too much on the source material and not how the material was used veers a little too close to “anyone could do that” territory for my tastes. A truly creative producer should render info about the song they sampled into little more than trivia. What matters is what they build out of that material, what new melodies and rhythms they write by following their creative intuition. In that spirit, I have not looked into what Premier sampled on “Moment of Truth” and if I happen to come across that information by chance while working on this piece, I won’t mention it here. For our purposes, DJ Premier is this music’s author. And boy did he write a great tune here!

Luckily it isn’t hard to see Premier’s fingerprints on “Moment of Truth”. Sampling effectively turns all recorded sound into a drum set worthy of Jorge Luis Borges. Premier plays the strings like a percussion instrument, abruptly restarting notes in a way that would be impossible with bows. Listen closely for chiming bells in the upper register, and you can hear where Premier is punching in different chunks of the original melody. This makes “Moment of Truth” feel like it’s constantly rolling back over itself, the way your memory might linger and return to a certain moment. The dusty quality of the vinyl Premier is manipulating only heightens this sense of the mind wandering back into the past. Along with scoring Guru’s own reflections on his struggles and the lessons he’s learned from them, this quality makes “Moment of Truth” feel classic twice-over. The same way that “Backstreets” refracted Springsteen’s memories of the early 60s through the 70s, “Moment of Truth” bottles up some unknown mist of the past in a 90s time capsule.

But maybe it would make more sense for me to show you what I mean.

I’m wearing an Aseethe shirt in this performance because that’s what I had on when I went to the studio. I didn’t know I was going to film this cover so I didn’t plan an outfit. Oh well, Aseethe are a cool band!

This cover came together really fast. Premier doesn’t muck around with dropping the beat in and out, so once I got a handle on the basic pattern there wasn’t much else to learn. There’s not really a chorus so much as a refrain, and once you’re in for the verses you’re in the whole time. I don’t think learning how to play this two bar loop revealed anything new to me about the song, but it felt great to play and gave me an excuse to listen to the song a bunch. The deeper into the groove I got, the more I appreciated Guru’s approach as a rapper. Lines that struck me as clumsy on first listen suddenly clicked once I could feel how they were responding to what I was playing. So how do I feel about “Moment of Truth” having listened to it a bunch? The song will face its own moment of truth below on the Drumming Upstream Leaderboard.

DRUMMING UPSTREAM LEADERBOARD

How to judge a song about judgement? I’ll admit that I’ve been stressed about writing this entry for weeks. Every time I open the draft I get a jolt of fear that I’m going to get it wrong, somehow misrepresent a dead man’s work, and reveal myself to be an insufficiently real New Yorker. I guess that’s why this entry has arrived after such a long delay.

To make this easier on myself, I’m going to use the currently highest rated rap song on the Leaderboard as a point of comparison. So, do I like “Moment of Truth” more than Jay-Z’s “Takeover”? I feel like I have a pair of minor deities hovering on my shoulders here. One says that “Moment of Truth” is the more significant work, more meaningful in the history of the genre than a song about the petty disputes of millionaires. “Moment of Truth”, emblematic of a place, time and ethos is more hip-hop than “Takeover”, surely? At the very least it does what hip-hop does best better than “Takeover”. The music builds something simultaneously new and timeless out of something old and the lyrics are an honest account of a man’s life under pressure told from his unique perspective. Then the deity on the other shoulder starts yelling “LAAAAAAAME”. I’ll give “Takeover” its credit. I think Jay-Z is the better rapper on just about every front, even if I have a fondness for Guru’s unique approach. “Takeover” is certainly more fun than “Moment of Truth”. But is fun all that matters here? Guru is no less quotable than Jay, and Premier’s beat is a masterpiece. In the end I’m going to place “Moment of Truth” one spot above “Takeover” and one below “Adam Raised A Cain.” Does that mean that I think Dad rock is definitively better than Dad rap? Man, I don’t know, cut me some slack here.

The Current Top Ten

“Moment of Truth” by Gang Starr

Thanks for reading, and for your patience. In the next entry I’ll tackle one of the primary influences on my own music with a cover of Phil Elverum’s old band The Microphones. Until then, have a great week!